THE TUNGUSKA NATIONAL UPRISING OF 1924-1925

Egor Petrovich ANTONOV,

Candidate of Historical Sciences

The main reason for the Tunguska national movement was the policy of terror of the era of "war communism" against the natives, carried out during the NEP period by the party and Soviet leadership of the Okhotsk coast. Chairman of the Special Commission of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee K.K. Baikalov in 1925 noted that the crimes against the civilian population by the Okhotsk authorities and the OGPU served as "one of the main reasons for the uprising."

Criminal and dubious persons made their way into the leadership of the Okhotsk district. The head of the OGPU, Kuntsevich, together with his friends, the former white bandits Kharitonov and Gabyshev, robbed the natives, recovering pre-revolutionary debts from them. By order of the platoon commander Suvorov, after severe torture, the Yakuts and Tungus I.S. were shot without trial or investigation. Gotovtsev, A.V. Atlasov, S.F. Ayanitov, A.V. Vinokurov, I.G. Sivtsev and others. In 1924, the OGPU arrested 64 Tungus and Yakuts, in 1925 - 250 people, a total of 314 people1.

The representative of the OGPU department, Gizhigi Osinsky, survived all honest and businesslike workers, and former White Guards, merchants and various kinds of crooks came in their place. In his entourage were D.S. Plotnikov, former head of the Kamchatka team, moonshine trader Platunov. Among them was the embezzler exiled to Kamchatka, who amassed a solid capital and aimed at "Chukotka kings."

Anyone who tried to oppose these iniquities was subjected to severe persecution. Chief of Police, A.P. Kryzhansky, who was awarded the Order of the Red Banner, was thrown into prison, into a cell where the floor was covered with a thick layer of dirt, without bunks and bedding. Kryzhansky's wife was arrested for 15 days. Her money and personal belongings were taken away from her, and during her imprisonment she was physically abused2.

The Okhotsk authorities committed lawlessness, terrorized and robbed the local population, as a result, the inhabitants of the Okhotsk coast became impoverished. The middle-income Tungus, who owned 40-50 deer in the pre-revolutionary period, had a little more than 10 heads in the 20s; the wealthy Evenk Gilemde, who had 1,500 deer, had only 70 deer left. Hungry reindeer herders began to include wild onions and seaweed in their daily diet. Member of the YATsIK delegation F.G. Sivtsev reported to the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the RSFSR that there was not a single person who could be classified as exploiters. In addition, visiting merchants from among the Yakuts and Russians were not averse to rob the gullible Evenks. There were times when they took eight squirrel skins for a pack of tea.

Under their influence, many Tungus became addicted to gambling into cards. Often, merchants used lies and slander to incite peaceful hunters and fishermen against Soviet power3.

Representatives of the official authorities did not know the language, traditions, culture, life of the Tungus. There were no national schools, not a single native worked in Soviet institutions and law enforcement agencies, there were not enough translators4.

In 1859, Okhotsk was annexed to the Amur province, in 1910-1911. The Okhotsk district was subordinated to the Kamchatka region, but in fact not a single case in the seceded territory was resolved without the sanction of Yakutsk. All the Tungus, wandering from the Okhotsk coast to Nelkan, were assigned to the Ust-Maisky ulus of the Yakut region. It turned out that they lived on the territory of the neighboring region, and no one prevented them from doing this. The border was only on paper. Trade, food warehouses, post office, schools, churches were assigned to the Lena region. Yakut Cossacks carried out military service in Okhotsk and Ayan, performed police duties, accompanied mail, were engaged in rescue work, etc.5

Tunguska rebel movement in 1924-1925. covered the Okhotsk coast and the southeastern regions of the Yakut Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. In the Yakut, Aldan, Verkhoyansk, Vilyui, Kolyma and Olekminsky districts, 13,000 Tungus lived. By that time, the Soviet government had not yet destroyed the traditional patriarchal way of life of the Tungus clans. Ancestors and "princes" enjoyed great influence among them. In the Tungus speech of 1924-1925. 600 people participated, i.e. 4.6%. Of these, in the Petropavlovsk region - 150, on the Okhotsk coast - 200 and in the northern districts - 250 people 6, including 175 Yakuts, i.e. almost 30% fought in the detachment of M.K. Artemiev - 72 people, P. Karamzin - 55, in Oymyakon - 20, in Verkhoyansk - 20, in Nelkan - 8 people; intellectuals from the Yakuts (3-5 people) took part in the movement7.

On May 10, 1924, the rebels (25-30 people) under the leadership of M.K. Artemiev occupied the village of Nelkan. Captured Soviet workers A.V. Akulovsky, F.F. Popov and Koryakin were released. On the night of June 6, the rebels numbering 60 people. under the leadership of Tungus P.V. Karamzin and M.K. Artemiev, after an 18-hour battle, captured the port of Ayan. The surrendered garrison was liberated by the Tungus and sent to Yakutia8. After these events, the rebels and the Red Army units did not take active hostilities9.

In June 1924, a congress of the Ayan-Nelkan, Okhotsk-Ayan and Maimakan Tunguses was held in Nelkan. The Provisional Central Tunguska National Administration was elected, which included the Tungus: Chairman-K. Struchkov, deputy - N.M. Dyachkovsky, members of the management - E.A. Karamzin and T.I. Ivanov. The congress approved P.V. Karamzin. The new leadership decided to create an independent state on the territory inhabited by the Tungus10.

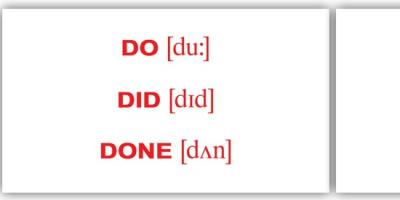

The rebels created their paraphernalia. They adopted the tricolor flag of the Tunguska Republic: white symbolized Siberian snow, green - forest, black - earth. The hymn “Sargylardaakh sa-khalarbyt” was also adopted11.

Thus, this movement was not a criminal one, since its leaders were political oppositionists who rallied around specific socio-political ideas. The leaders of the rebels had ideas about jurisprudence. This is evidenced by their demands for national self-determination, individual rights, the rights of small ethnic groups, and the creation of an independent national-territorial entity. The reason for the dissatisfaction of the rebels was the inequality of the rights of large and small peoples in the creation of a national-territorial federation.

In addition to political insurgents put forward demands of an economic and cultural nature. For example, they proposed restoring the ancient routes Yakutsk - Okhotsk, Nelkan - Ayan and Nelkan - Ust-Maya12, i.e. sought to establish former economic ties with Yakutia; developed a set of measures for the economic and cultural development of the Okhotsk coast zone.

These demands coincided with the position of the party and Soviet leadership of the YASSR, which advocated the formation of an autonomous Tunguska region and for granting Yakutia the right to enter the foreign market. Attention was drawn to the fact that in the pre-revolutionary period there was a duty-free importation of goods by the Sea of Okhotsk. P.A. Oyunsky, in his letter to the Council of Nationalities of the Supreme Soviet and the Yakut representation in Moscow, proposed to annex the Okhotsk coast to Yakutia, staff the local Revolutionary Committee with Tungus and Yakuts, abolish the pre-revolutionary system of elders and organize Soviets, whose chairmen should be Yakut communists. The first secretary of the Yakut Regional Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, E. G. Pestun, believed that the Okhotsk coast was economically closely connected with Yakutia13. The party and Soviet leadership, headed by M.K. Ammosov, I.N. Barakhov, S.V. Vasiliev in the General Plan for the Reconstruction of the National Economy of the Yakut Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic outlined a project for a transport connection with the Primorsky Territory through access to the Sea of Okhotsk14.

E.G. Pestun in April 1925 spoke about the ties of the rebels with the Japanese, Americans and French. In the summer of 1924, a Japanese schooner entered the port of Ayan. According to one of the rebel leaders Yu.A. Galibarov, there was a Frenchman who called himself "professor" (name unknown). He and the Japanese captain promised to support Yu.A. Galibarov and his accomplices. At the same time, the English company Hudson Bay, which had a trading concession in Kamchatka, through its agents supplied the Tungus with Winchester guns and the necessary supplies.

On March 10, 1925, Khalin, authorized by the OGPU for the Amgino-Nelkansky district, reported information received from the rebels who had surrendered. According to them, a Japanese cruiser, on board of which there was a certain general, visited the port of Ayan. M.K. Artemiev negotiated with him

on the supply of weapons and food to the rebels. Subsequently, the commander of one of the rebel detachments, I. Kanin, received from M.K. Artemyev secret notice, which dealt with the receipt of Japanese assistance. On December 5, 1925, at a meeting of the Tungus of the Kupsky nasleg, the commander of the rebel detachment N.N. Bozhedonov spoke about the need to establish contacts with Japan and America15. However, K.K. Baikalov came to the conclusion that foreigners had nothing to do with the Tunguska rebellion, the rebels maintained only commercial relations with them.

The participants in the movement did not want bloodshed at all and were ready to resolve the urgent conflict through peaceful negotiations. K.K. Baikalov noted that the rebels released all the captured Red Army soldiers and employees of the OGPU. In this regard, the "savage natives" turned out to be smarter than the Okhotsk authorities. But official circles chose violence as a method of resolving the conflict. In 1924, the Yakut District Executive Committee published an appeal “To all working Yakuts, Tungus. To the national intelligentsia”, in which the rebels appeared as “criminal robbers”, “arrogant robbers”, “criminals”17.

The cultural and educational society "Sakha Omuk" adopted a resolution stating that there were no reasons due to which the rebellion of 1921-1922 began: autonomy was proclaimed and a humane policy was pursued in relation to the former rebels, representatives of the intelligentsia and the peasantry. The new movement was assessed as an adventure and criminal banditry, leading to economic ruin. An appeal was made to members of Sakha Omuk to take part in the campaign against the rebels, to involve former rebels in propaganda work among the population and participants in the new movement18.

In September 1924, by order of Kuntsevich, a detachment of the Okhotsk OGPU (45 people) headed by V.A. was sent to the village of Ulya. Abramov and Andreeva. According to information there were rebels. The Red Army soldiers shot three Russian fishermen, three Tungus (Mikhail and Ivan Gromov, I. Sokolov), Yakut M. Popov. Osenin's Tungus died from severe beatings.

February 7 cavalry detachment I.Ya. Stroda captured Petropavlovsk without a fight. A group of rebels led by I. Kanin at that time was on the opposite bank of the Aldan, one verst from the river. They were attacked by the Strodovites, a shootout ensued. The rebels fled to Nelkan, from where M.K. Artemiev with a detachment of 30 people20

From February 21 to February 22, 1925, the Tungus detachment P.V. Karamzin, numbering 150 people, armed with 2/3 "thin Berdans", with one machine gun "Shoshe", occupied Novoye Ustye, located 8 versts from Okhotsk, with a night attack. The capture was a success, despite the double numerical superiority and technical superiority of the Reds, who had 317 people armed with three-line rifles, machine guns (one Maxim, one Lewis, two Colts, three Shoshe). Alpov, the head of the military garrison of Okhotsk, did not dare to attack the rebels and decided only to defend the port.

The rebels confiscated the goods of the Nelkan branch of the Hudson Bay company and appointed Y. Galibarov as the head of the warehouse22. In Novy Ustye, they had in their hands up to 10 thousand poods of food worth 100,000 rubles, in Oymyakon - various goods worth about 25 thousand rubles, in Abyi - furs worth 25 thousand rubles. In the occupied areas, the rebels got the shops and warehouses of Yakutpushnina, the Kholbos cooperative, and other economic and trade organizations. There were cases of robberies of the civilian population, when horses, food supplies, hay were taken away23.

On the morning of March 4, the rebels raided Ust-Maiskoye. Fifty Red Army men who went there were ambushed. Having lost 9 killed and 8 wounded, the Reds withdrew to Petropavlovsk. For the second time this

area was sent a detachment of Red Army soldiers numbering 80 people. After a short skirmish, the rebels fled. March 31 group M.K. Artemyeva occupied the Sulgachi area; On April 8, the detachment of G. Rakhmatulli-on-Bossoika entered the village of Abaga. Cavalry I.Ya. Strode, 20 km from Petropavlovsk, surrounded and forced the group of S. Kanin to surrender25. Of the 13 surrounded rebels, two died, three fled to Artemyev, and 8 people, including Kanin himself, laid down their arms26.

During the NEP in our country, the central Party and Soviet bodies tried to resolve national problems by peaceful means. General Secretary of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks I.V. Stalin sent instructions to the commissioner of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee K.K. Baikalov, who led the liquidation of the Tunguska rebellion. It said: “The Central Committee, taking into account all the above considerations, finds it expedient to peacefully liquidate the uprising, using military forces only if this is dictated by necessity ...”27

The Party and Soviet bodies of the Yakut ASSR, guided by orders from the center, sent a commission to conduct peace negotiations, consisting of: P.I. Orosina, A.V. Davydov and P.I. Filippov, who attended the Second Tunguska Congress in January 1925. This delegation informed the audience about political life in Yakutia and new construction, but the congress was distrustful of their arguments. The Tungus in the commission did not see a legal entity that could have significance and weight in politics. Therefore, the population considered the members of the delegation to be of little authority, and quite reasonably the question arose: "Can yesterday's rebel give someone a firm amnesty?"

The Tunguska Congress, through a peaceful delegation, submitted to the YATsIK of the YASSR the following requirements: 1) separation of the Okhotsk coast from Far East and accession to Yakutia; 2) granting the right to the Tungus themselves to resolve political, economic and cultural issues; 3) removal from power of the communists who pursued a policy of terror28. M.K. Artemiev wrote that if the Tungus and Yakuts fall under the yoke of foreign states or remain under the rule of the communists, they will turn into slaves. "No party defends the nation as it defends its native people." Artemiev suggested that party and non-party natives unite and jointly defend national interests29.

Chief of Staff M.K. Artemyev with 60 rebels was in the Myryla area (160 km from Amga). A YATsIK delegation headed by R.F. arrived there. Kulakovsky, who signed the armistice agreement. On April 30, YATsIK sent an official delegation consisting of E.I. Sleptsova, F.G. Sivtsev and N. Boldushev.

In May 1925, during peace negotiations, both sides managed to find a common language. M.K. Artemiev became convinced that the communists who were not involved in the policy of terror were at the head of Yakutia; a national revival is underway in the republic, and the issue of joining Tungusia to the YASSR is under discussion30. As a result of successful negotiations, a peace agreement was concluded on May 9, and the detachment of M.K. Artemyeva "unanimously decided to lay down arms." On July 18, the detachment of P.V. Karamzin in the Bear's Head area, located 50 km from Okhotsk, also capitulated. In total, 484 rebels from the detachment of M.K. Artemiev and 35 rebels of P.V. Karamzin31.

On June 22, 1925, at the regional party conference in Yakutsk, K.K. Baikalov expressed the opinion that the regional committee made mistakes: he attracted amnestied rebels to Soviet work, gave them material assistance, and extended the amnesty to Russian White Guards. M.K. Ammosov did not agree with this and said that the involvement of former rebels, who are closely associated with the natives, advises them and wins the trust of the natives. The method of class stratification in relation to a backward people is inappropriate. The amnesty of the Russian White Guards was caused by the fact that the white generals A.N. Pepelyaev and Slashchev. P.A. Oyunsky gave a certificate that the former rebels YATsIK issued 50 rubles. for travel and a certificate by which they could receive a loan of up to 100 rubles. for farming. These measures were due to the fact that the participants in the movement were the impoverished, without a stake and a court, the Tungus and Yakuts. The provision of assistance contributed to their transition to a peaceful life. E.G. Pestun noted that not a single merchant, policeman or White Guard officer has yet been amnestied.

Officers need a personal approach. In 1923, a group of white officers was set free in Abyei, as a result, it was possible to liquidate the center of the insurrection in a remote and hard-to-reach area, "where they could not be taken by any armies." In 1924, the former White Bochkarev rebels no longer led the rebel detachments, in particular, Colonel Gerasimov in Oymyakon refused to head the rebel headquarters32.

On August 10, 1925, a congress of the Tungus of the Okhotsk coast, organized by the Dalrevkom, opened in Okhotsk, which was attended by representatives of 21 Tungus clans and three Yakut regions. They adopted a resolution on trade, hunting and fishing, health care, public education; special attention was paid to the organization of tribal councils33. On August 23, at a meeting of residents of Nelkan, the chairman of the Special Commission of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee K.K. Baikalov, F.G. Sivtsev and T.S. Ivanov. The meeting participants noted the strengthening of the international position of the USSR, the achievement of pre-war indicators by industry and agriculture, and the peaceful liquidation of the rebellion by the government of Yakutia. It was emphasized that the Soviet government is the only defender of the oppressed masses. The "Main Tunguska National Administration" resigned, and a revolutionary committee was formed in Nelkan. It included P.S. Zhergotov, I.N. Borisov and Yu.M. Trofimov.

On August 25, a meeting of citizens of Nelkan was held, at which K.K. Baikal. He promised that the demands of the Tungus people would be implemented and announced an amnesty for the rebels. But at the same time, he added that all armed uprisings against the Soviet regime would be suppressed by force without any negotiations with the rebels34. The “Main Tunguska National Administration” adopted an act that the national self-determination of the Tunguska people was secured by decisions made by the Central Executive Committee of the USSR, the Council of Nationalities of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR and the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. The adoption of such a resolution would make it possible to stop the fragmentation of a single Tungus ethnic group into various administrative units, such as the Yakut Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, Primorsky and Kamchatka regions. They consider their fragmented state

or as a "product of monarchist policy." The main goal of the participants in the movement was to unite the Tungus people around a single national-territorial unit, which was to become part of Yakutia35.

1 FNA RS (I). F. 3, op. 20, d. 32, l. 170-169, 140, 150-149, 114.

2 Ibid. L. 1bb-165.

3 AT RS (Y) F. 50, op. 7, d. 6, l. 110, l. 77; d. 10, l. 105-106.

4 Antonov E.P. Tunguska uprising: mistakes could have been avoided... // Ilin. Yakutsk, 1995, p. 94.

5 ON RS (I). F. 50, op. 7, d. 10, l. 83-84; d. 5, l. 70.

6 Ibid. D. 6, l. 4, 7-8.

7 FNA RS (I). F. 3, op. 20, d. 32, l. 110, 115.

8 Gogolev Z.V. The defeat of anti-Soviet uprisings in 1924-1925 and 1927-1928. //Scientific messages. Issue. 6. Yakutsk, 1961. P. 25; Antonov E.P. Tunguska uprising. S. 94.

9 FNA RS (I). F. 3, op. 20, d. 32, l. 115.

10 Gogolev Z.V. Defeat of anti-Soviet uprisings. S. 25; Antonov E.P. Tunguska uprising. pp. 94-95.

11 Ibid. S. 25.

12 Antonov E.P. Tunguska uprising. S. 94.

13 ON RS (I). F. 50, op. 7, d. 6, l. 57, 10, 28.

14 Argunov I.A. Social sphere of lifestyle in the Yakut ASSR. Yakutsk, 1988, p. 68.

15 ON RS (I). F. 50, op. 7, d. 6, l. 7; d. 3, l. 164, 57.

16 FNA RS (I). F. 3, op. 20, d. 32, l. 170-171.

>7 Ibid. Op. 3, d. 270, l. 33.

18 ON RS (I). F. 459, op. 1, d. 72, l. 2.

19 FNA RS (I). F. 3, op. 20, d. 32, l. 147.

20 Gogolev Z.V. Defeat of anti-Soviet uprisings. S. 26.

21 FNA RS (I). F. 3, op. 20, d. 32, l. 147.

22 Antonov E.P. Tunguska uprising. S. 95.

23 Gogolev Z.V. Defeat of anti-Soviet uprisings. S. 26.

24 ON RS (I). F. 50, op. 7, d. 3, l. 162-163.

25 Gogolev Z.V. Defeat of anti-Soviet uprisings. S. 26.

26 Basharin G.P. Socio-political situation in Yakutia in 1921-1925. Yakutsk, 1996. S. 267.

27 Pesterev V.I. Historical miniatures about Yakutia. Yakutsk, 1993, p. 108.

28 Gogolev Z.V. Defeat of anti-Soviet uprisings. S. 26; Antonov E.P. Tunguska uprising. S. 25.

29 ON RS (I). F. 50, op. 7, d. 3, l. 250; d. 5, l. 18.

30 Antonov E.P. Tunguska uprising. S. 96.

3> Basharin G.P. Socio-political situation. S. 268.

32 FNA RS (I). F. 3, op. 3, d. 271, l. 55-56, 58.

33 Gogolev Z.V. Defeat of anti-Soviet uprisings. pp. 27-28.

34 ON RS (I). F. 50, op. 7, d. 10, l. 15-16.

35 PFA AN (St. Petersburg branch of the archive of the Academy of Sciences). F. 47, op. 1, d. 142, l. 7.

SUMMARY: The author of the article Candidate of Historical Sciences E. Antonov tells about 1924-1925 and thinks that the main reasons of the Tungus Uprising was the policy of terror of the epoch of military communism against aborigines that was led by party Soviet leaders in Okhotsk coast.

In 1924-1925. The civil war in Russia has actually ended. The Soviet Union already existed, the foundations of a new Soviet statehood were being laid. But many of the national outskirts of the country remained restless. This was due to the socio-economic and political processes that took place in the national regions against the backdrop of the establishment of Soviet power. First of all, we are talking about confronting the numerous innovations that the victory of the Bolsheviks in the revolution and civil war. The course towards the creation of national autonomies, which, as it seemed, was supposed to play an important role in increasing the sympathy of national regions for the central government of the Soviet Union, in fact, contributed to the growth of national self-consciousness even of those peoples who in tsarist Russia were not at all considered serious political actors. . The Soviet national policy was generally controversial and the opinions of researchers - historians and modern politicians still differ radically about whether the reform of its political and administrative division in the early years of Soviet power brought positive or negative consequences to the country.

Causes of the uprising

For several years, armed resistance to the Soviet regime was provided by insurgent detachments operating on the territory of Eastern Siberia. The reasons for the uprisings that broke out in Eastern Siberia were most often not related to the ideological opposition to the communist authorities. As a rule, the dissatisfaction of the population with the policy of the Soviet government in the sphere of economic relations and, in particular, the abuse of official position, which was characteristic of many bosses and "bosses" at the local level, played a role. Although, of course, there were also attempts to give the protest movements a deeper ideological background. As for the social base of the movement, in the first years of Soviet power, the traditional social structure of many peoples of Eastern Siberia had not yet been violated, which retained their tribal way of life and, accordingly, it was on this basis that they could consolidate to oppose the new regional authorities.

Mid 1920s was marked by a major uprising of the indigenous population of the Okhotsk coast and the southeastern regions of Yakutia. The vast region of Yakutia, which included the Aldan, Verkhoyansk, Vilyui, Kolyma, Olekminsky and Yakutsk districts, was inhabited by the Tungus. It should be noted that Tungus in Tsarist Russia and in the first years of Soviet power were traditionally called Evenks, Evens and part of the Yakuts, who lived in close contact with the Evenks. The Tungus population in this region reached 13 thousand people. At the same time, during the period under review, the Tungus, for the most part, retained their traditional way of life and their characteristic social structure. However, according to a number of researchers, in reality, the Tungus population of the region under consideration was rather Yakut. Those Evenks who lived in the region were largely Yakutized and used the Yakut language.

The dissatisfaction of the indigenous population of the region was caused by the separation of the Okhotsk Territory from Yakutia, which followed in April 1922. As a matter of fact, the Okhotsk Territory was assigned to the Kamchatka Region as early as 1910-1911, but until 1922 there were no real borders between Yakutia and the Okhotsk Territory. The Tungus quietly roamed the territory of both the Okhotsk Territory and Yakutia. At the same time, schools and churches were subordinate to Yakutsk, from Yakutia (Lena Territory) Cossacks arrived in the Okhotsk Territory, who served in law enforcement. The situation changed in 1922, after the actual separation from Yakutia. This led to an increase in tension associated with the neglect of the local population by the authorities. If in Yakutia the transition to autonomy was gradually carried out, as a result of which the development of a nationally oriented system of education and culture began, and the Soviet leadership behaved more restrained, then the small Tungus population of the Okhotsk Territory became, in literally, a victim of arbitrariness.

First, unlike Yakutia, there were no national educational institutions in the Okhotsk Territory, no language was studied, and the appointed Soviet leaders did not speak it, and most of the Tungus did not know Russian or spoke it with difficulty. In turn, the Tungus were isolated from participation in the activities of government and administration: as the historian E.P. Antonov, not a single Tungus was involved in the service in law enforcement agencies, in government bodies (Antonov E.P. The Tunguska national uprising of 1924-1925 / / Russia and ATR. 2007, No. 4. P. 42). The new Soviet bosses inherited the worst traditions of the Russian pre-revolutionary authorities in the region in terms of impunity for abuses and crimes against local residents. So, the local authorities were engaged in open robbery of the indigenous population, taking away deer, dogs and imposing huge taxes.

The confiscation of deer actually ruined the once prosperous Tungus clans that roamed the territory of the Okhotsk Territory. Many Evenks lost their livelihood - out of a livestock of 40-70-100, or even a thousand deer, people left 10-20 deer each. The deterioration of material well-being was accompanied by constant harassment and bullying by representatives of the authorities, in which, as even the Soviet authorities investigating the situation in the Okhotsk Territory, later admitted, criminal elements were infiltrated. Among them were not only greedy and bribe-takers, but also outright bandits, who before the revolution were engaged in the fraudulent acquisition of furs from the local population. Among the employees of local Soviet authorities were even members of the White Partisan movement, who were later rehabilitated and entered the Soviet service. It is significant that not all of the representatives of the local Soviet authorities participated in the robbery of the local population - some tried to protest, but they themselves risked becoming victims of lawlessness. Therefore, when the indignation among the indigenous population escalated the situation to an extreme point, there was a social explosion. An uprising began against the local authorities.

The beginning of the uprising. Mikhail Artemiev

On May 10, 1924, a detachment of 25-30 rebels captured the village of Nelkan. On the night of June 6, 1924, a detachment of 60 rebels managed to defeat the Soviet garrison of the port of Ayan and capture the settlement and port. It is significant that the Tungus did not demonstrate bloodthirstiness towards Soviet managers - for example, Soviet employees captured in Nelkan were released, and the rebels also released the surrendered garrison of the port of Ayan to Yakutia, having previously disarmed. The rebels did not kill any of the Soviet employees.

In the same June 1924, the initially spontaneous insurrectionary movement began to take on more organized forms. In Nelkan, captured by the rebels, a congress of the Ayan-Nelkan, Okhotsk-Ayan and Maimakan Tunguses was convened, at which its delegates elected the Provisional Central Tunguska National Administration. K. Struchkov was elected chairman of the department, N.M. Dyachkovsky, members of the management -T.I. Ivanov and E.A. Karamzin. As for the military leadership of the rebel detachments, it was carried out by P.V. Karamzin and M.K. Artemiev. Pavel Karamzin was a representative of the extremely influential Tungus princely family in the local areas, therefore he was a kind of symbol of the uprising - the Tungus still had very strong traditional components in their social life, so the presence of people from the princely family at the head of the rebels automatically attracted the broad masses of the Tungus to the side of the latter population. However, in many ways, rather Mikhail Artemyev should be considered one of the most active initiators of the uprising - he commanded a detachment that took Nelkan and the port of Ayan, and also participated in the direct development of the program foundations of the insurgent movement. Among other local residents, Artemiev was distinguished by his literacy and the presence of a life experience atypical for reindeer herders.

Mikhail Konstantinovich Artemiev was born in 1888 in the Betyunsky nasleg of the Boturus ulus in a peasant family. Unlike many other "foreigners", as the locals were called in tsarist times, Artemyev was lucky - he was able to get an education after graduating from the fourth grade of the Yakut real school. Literacy allowed Mikhail to take the position of a clerk in the Bethune nasleg, and then become the foreman of the Uranai and Bethune tribal administrations. Artemiev managed to work as a teacher in the Amga settlement. Like many educated representatives of the national minorities of Siberia, Artemiev initially supported the establishment of Soviet power. On March 17, 1920, he took the post of volost commissar, and was also chairman of the revolutionary committee. However, rather quickly, Artemiev turned from an active supporter of Soviet power into a participant in the rebel movements. He fought against the Bolsheviks in the rebel detachments of Korobeinikov, then served with General Pepelyaev. The defeat of the Pepelyaevites forced Artemyev to flee to the taiga, where, being in an illegal position, he led the rebel detachment.

Mikhail Konstantinovich Artemiev was born in 1888 in the Betyunsky nasleg of the Boturus ulus in a peasant family. Unlike many other "foreigners", as the locals were called in tsarist times, Artemyev was lucky - he was able to get an education after graduating from the fourth grade of the Yakut real school. Literacy allowed Mikhail to take the position of a clerk in the Bethune nasleg, and then become the foreman of the Uranai and Bethune tribal administrations. Artemiev managed to work as a teacher in the Amga settlement. Like many educated representatives of the national minorities of Siberia, Artemiev initially supported the establishment of Soviet power. On March 17, 1920, he took the post of volost commissar, and was also chairman of the revolutionary committee. However, rather quickly, Artemiev turned from an active supporter of Soviet power into a participant in the rebel movements. He fought against the Bolsheviks in the rebel detachments of Korobeinikov, then served with General Pepelyaev. The defeat of the Pepelyaevites forced Artemyev to flee to the taiga, where, being in an illegal position, he led the rebel detachment.

About 600 Evenks and Yakuts took part in the Tunguska uprising, there were also a few representatives of the Russian population of the region. From the very beginning of the movement, it took on the character of a political one, since it put forward quite clear political demands - the creation of a national state entity. In the economic area, the participants in the uprising demanded the restoration of the Yakutsk-Okhotsk, Nelkan-Ayan and Nelkan-Ust-Maya tracts, which testified to their desire to improve the financial situation of the Okhotsk Territory and revive its trade and economic ties with Yakutia. At the same time, these requirements would also be beneficial for the economic development of Yakutia, since if these routes were recreated, Yakutia would have the opportunity to trade by sea from the coast of Okhotsk. The seriousness of the rebels' intentions was also confirmed by the adoption of their own tricolor flag, on which the white stripe meant Siberian snow, green - taiga forests, and black - native land.

Thus, the ideology of the rebellion rather satisfied the interests of the Yakut population, since the rebels sought to turn Yakutia into a region with access to the sea through the Okhotsk Territory. In the event that the Soviet government went to satisfy the demands of the rebels for the unification of Yakutia and the Okhotsk Territory, a new union republic would actually be formed, which would greatly strengthen its positions. Naturally, such a national formation, covering a significant part of Eastern Siberia with access to the sea, was not included in the plans of the central leadership of the country - after all, the danger of separatist tendencies was obvious. Especially in that difficult period, when lobbyists for Japanese interests were active in the Far East and Eastern Siberia.

Fighting and surrender of the rebels

After the movement declared its political positions, the Soviet authorities of Yakutia were greatly concerned about the ongoing events. The insurgent movement was characterized as a manifestation of banditry and criminality, at the same time the rebels were accused of collaborating with Japanese special services interested in destabilizing the situation in Eastern Siberia and the Far East. The Yakut District Executive Committee issued an appeal “To all working Yakuts, Tungus. To the national intelligentsia”, which stated the criminal nature of the insurgency in the Okhotsk Territory. In September 1924, the head of the OGPU of the Okhotsk district, Kuntsevich, sent an OGPU detachment of 45 people under the command of V.A. Abramov. "Abramovtsy" shot three Russian fishermen, three Tungus and one Yakut.

The conflict entered its most active phase at the beginning of 1925. In early February, a cavalry detachment under the command of the famous Strod was sent against the rebels. Thirty-year-old Ivan Yakovlevich Strod (1894-1937) was considered one of the most experienced Red Army commanders in the Far East and Eastern Siberia. In the past, an anarchist, and then a supporter of the Soviet regime, Strode replaced the legendary Nestor Kalandarishvili as commander of the cavalry detachment. Although Strod received combat experience even before the start of the Civil War, he participated in the First World War, was awarded the St. George Cross and received the rank of ensign. During the first half of the 1920s. Strode commanded the cavalry detachment named after Kalandarishvili, led the defeat of the White partisan units of Pepelyaev, Donskoy, Pavlov. It was assumed that an experienced commander, who knew perfectly the tactics of the partisans and smashed the white detachments of the professional military, could easily cope with the Evenk rebels. Indeed, on February 7, 1925, the Strod detachment occupied Petropavlovsk. On the banks of the Aldan, the Evenks, commanded by I. Kanin, clashed with the Strod cavalrymen. The rebels retreated to Nelkan.

The conflict entered its most active phase at the beginning of 1925. In early February, a cavalry detachment under the command of the famous Strod was sent against the rebels. Thirty-year-old Ivan Yakovlevich Strod (1894-1937) was considered one of the most experienced Red Army commanders in the Far East and Eastern Siberia. In the past, an anarchist, and then a supporter of the Soviet regime, Strode replaced the legendary Nestor Kalandarishvili as commander of the cavalry detachment. Although Strod received combat experience even before the start of the Civil War, he participated in the First World War, was awarded the St. George Cross and received the rank of ensign. During the first half of the 1920s. Strode commanded the cavalry detachment named after Kalandarishvili, led the defeat of the White partisan units of Pepelyaev, Donskoy, Pavlov. It was assumed that an experienced commander, who knew perfectly the tactics of the partisans and smashed the white detachments of the professional military, could easily cope with the Evenk rebels. Indeed, on February 7, 1925, the Strod detachment occupied Petropavlovsk. On the banks of the Aldan, the Evenks, commanded by I. Kanin, clashed with the Strod cavalrymen. The rebels retreated to Nelkan.

However, on the night of February 21-22, 1925, a detachment of 150 Evenks under the command of P.V. Karamzin managed to capture New Mouth. Although the Evenks were opposed by the Red Army garrison of 317 fighters and commanders armed with seven machine guns, the rebels managed to gain the upper hand and capture the village. After that, the rebels seized goods stored in warehouses, with a total value of 100 thousand rubles in Novy Ustye, 25 thousand rubles in Oymyakon. Naturally, the rebels appropriated the furs stored in the warehouses of Soviet organizations. In relation to the local population, however, many rebels behaved no better than the Soviet leaders, against whom they raised an uprising. So, the fighters of the rebel detachments seized food from the civilian population, took away horses.

Continuing raids in the Okhotsk Territory, on March 4, 1925, the rebels invaded Ust-Maiskoye. A detachment of 50 Red Army soldiers failed to drive them out of the village, after which the Red Army soldiers were forced to retreat, losing nine soldiers dead and eight wounded. But the second operation of the Red Army detachment, this time with 80 fighters and commanders, turned out to be more successful - the rebels retreated from Ust-Maisky. In early April, the Red Army soldiers of Ivan Strod managed to surround a detachment of the rebel S. Kanin of 13 people. Only three rebels managed to escape, two were killed, and the remaining eight, including Kanin, who commanded the detachment, were captured.

Rebel detachment, in the center - Pavel Karamzin

In the meantime, seeing that the use of force to suppress the insurgent movement in the Okhotsk Territory only entailed further embitterment of the indigenous population and did not contribute to a radical solution to the problem, the leading bodies of the Soviet government decided to change their policy in the direction of reaching a compromise. Ivan Strod played a significant role in resolving the conflict situation, having studied the psychology and customs of the local population well for many years of life and service in the taiga of Eastern Siberia and the Far East.

Mikhail Artemiev, who lodged with his rebels in Myryla, met with a delegation from the Central Executive Committee of Yakutia led by R.F. Kulakovsky. An armistice agreement was signed, and on April 30, a delegation from the Yakut Central Executive Committee, which included E.I. Sleptsov, F.G. Sivtsev and N. Boldushev. They promised Artemyev that the issue of reuniting the region with Yakutia would be resolved in the near future. The result of the negotiations was the addition of a detachment of M.K. Artemiev on May 9, 1925. Two months later, on July 18, a detachment of another authoritative commander, P.V. Karamzin. Thus, 519 Evenk and Yakut rebels laid down their arms. Since the central Soviet leadership at that time was extremely cautious in resolving issues in the sphere of interethnic relations, local authorities also focused on soft methods in relation to the rebels.

On August 10, 1925, Dalrevkom organized a congress of the Tungus of the Okhotsk coast in Okhotsk, in which delegates from 21 Tungus clans and three Yakut regions took part. On August 23, 1925, a congress of the Main Tunguska National Administration was held in Nelkan, at which representatives of the Soviet government F.G. Sivtsev, T.S. Ivanov and Chairman of the Special Commission of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee K.K. Baikal. As a result of the reports of the Soviet leaders, the Tunguska Administration announced the resignation of its powers and self-dissolution. The importance of resolving the conflict situation peacefully was emphasized. However, K.K. Baikalov, who headed the Special Commission of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, as a result of investigating the causes of the uprising of 1924-1925, concluded that the uprising was provoked by the criminal activities of the authorities of the Okhotsk Territory and employees of the local OGPU.

At the same time, the chairman of the Special Commission of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee also denied accusations of cooperation between the rebels and Japanese and American agents, which had previously been distributed by the Yakut Soviet press.

The representative of the Okhotsk-Yakut military expedition of the OGPU Andreev made the following conclusion about the real reasons for the uprising: “The main reason for the dissatisfaction of the Tungus with the existing government is their terrible impoverishment. The death of deer due to hooves, the invasion of wolves, the pestilence of dogs, the lack of loans from the economic authorities, the illness and high mortality of the Tungus due to the complete lack of medical care, the inability to acquire basic necessities - these reasons together ruined the already low-ranking primitive economy of the Tungus. The error of the local authorities lies in the following: there was no connection with the native population, they were not Soviet workers, but were officials who treated their duties as official, all the circular orders of the center, written for most of the provinces of Soviet Russia, but unsuitable for the Okhotsk Territory , they were blindly put into practice "(Quoted by: T.V. Fonova. Administrative-territorial definition of the village of Nelkan in the 20s - 30s of the last century. Report of the 2nd scientific and practical conference "Meet the Sun!". August 2, 2008).

The participants of the Tunguska uprising were amnestied by the Soviet authorities. Moreover, many rebels were given loans to start a household. This step of the Soviet government was explained by the fact that really impoverished people took part in the uprising, who could hardly be accused of kulaks or bourgeois sentiments. Therefore, the Soviet leadership tried to hush up the conflict and help those Evenks and Yakuts who were in financial distress. Some of the leaders of the uprising were even accepted into the service of Soviet administrative institutions. In particular, Mikhail Artemyev is the most prominent field commander Tungus uprising - even worked as a secretary of the Nelkan volost, then was a translator and guide.

"Confederalists". Second rebellion

However, in the future, many former participants in the uprising again turned out to be dissatisfied with the policy of the Soviet government. Despite the fact that the Soviet leadership made promises to satisfy the interests of the indigenous population, in reality the situation has not changed much. Most likely, this is precisely what made Mikhail Artemyev in 1927 join the next uprising that took place in Soviet Yakutia and entered Eastern Siberia as the “xenophonism”, or “confederalist movement”. The Tungus also took part in the "confederalist movement", although for the most part, both in composition and in terms of the goals of the movement, it was focused on the Yakuts. The essence of the confederalist movement was the desire to turn the Yakut ASSR into a union republic, which meant increasing the representation of the Yakuts in the Council of Nationalities of the USSR, the authorities in Yakutia, as well as increasing self-government in the republic. In addition, there was also a nationalist overtone - the Confederalists opposed the settlement of Yakutia by settlers from the European part of Russia, as they saw them as a threat to the economic well-being of the Yakut population. The peasants, who occupied agricultural land, thereby deprived the Yakuts of pastures.

At the origins of the confederalist movement in Yakutia in 1925-1927. stood Pavel Vasilyevich Ksenofontov (1890-1928). Unlike Artemiev, although literate, but with only four classes of a real school behind him, Ksenofontov could be called a real representative of the Siberian intelligentsia. A native of a noble Yakut family, Ksenofontov graduated from the law faculty of Moscow University and in 1925-1927. worked in the People's Commissariat of Finance of the Yakut ASSR. When armed uprisings of the local population began in Yakutia in April 1927, Ksenofontov created the Young Yakut National Soviet Socialist Confederalist Party. In fact, it was her views that determined the main line of the Yakut uprising in 1927. In addition to Ksenofontov, Mikhail Artemyev also stood at the head of the rebels.

At the origins of the confederalist movement in Yakutia in 1925-1927. stood Pavel Vasilyevich Ksenofontov (1890-1928). Unlike Artemiev, although literate, but with only four classes of a real school behind him, Ksenofontov could be called a real representative of the Siberian intelligentsia. A native of a noble Yakut family, Ksenofontov graduated from the law faculty of Moscow University and in 1925-1927. worked in the People's Commissariat of Finance of the Yakut ASSR. When armed uprisings of the local population began in Yakutia in April 1927, Ksenofontov created the Young Yakut National Soviet Socialist Confederalist Party. In fact, it was her views that determined the main line of the Yakut uprising in 1927. In addition to Ksenofontov, Mikhail Artemyev also stood at the head of the rebels.

Initially, the Confederalists planned to speak out on September 15, but the plans were thwarted by the counterintelligence operations that had begun - P.D. informed the Soviet leadership about the upcoming uprising. Yakovlev, who served as Deputy People's Commissar of Internal Trade of Yakutia. Nevertheless, on September 16, an insurgent detachment was created, led by Ksenofontov, Mikhailov and Omorusov. In October 1927, the rebels under the command of Artemyev occupied Petropavlovsk, including a detachment of 18 local Tungus. Olmarukov's detachment occupied the village of Pokrovsk.

Detachments of Ksenofontov and Artemyev occupied the villages of Ust-Maya, Petropavlovsk, Nelkan, Oymyakon and a number of others. In two months, the uprising covered the territory of five Yakut uluses, and the number of rebels increased to 750 people. At the same time, the occupation of settlements was carried out in fact without real clashes with the Red Army or the police. In order to counter the rebels, back in early October 1927, the Soviet leadership convened an Extraordinary Session of the Yakut Central Executive Committee. It was decided to assign the responsibility for suppressing the uprising to the North-Eastern Expedition of the OGPU. On November 18, Mikhailov's detachment clashed with an OGPU unit.

On December 4, 1927, in the village of Mytattsy, the rebels elected the Central Committee of the Young Yakut National Soviet Socialist Confederalist Party and the general secretary of the party, who became Ksenofontov. The Central Committee of the party included P. Omorusov, G. Afanasiev and six other rebels, the Central Control Commission of the party included I. Kirillov, M. Artemyev and A. Omorusova. On December 16, 1927, the rebels split into several detachments. A detachment of 40 rebels under the command of Mikhailov moved to the East Kangalassky ulus, a detachment of Kirillov and Artemiev of seventy people - to the Dyupsinsky ulus. As they advanced, the rebels gathered the inhabitants of the occupied villages and read appeals to the people in the Yakut and Russian languages. Meanwhile, the OGPU detachments were moving in the footsteps of the rebels. The operation against the Confederalists was commanded by the same Ivan Strod, who had suppressed the Tunguska uprising two years earlier.

Surrender of the Confederates

Like the Tunguska uprising of 1924-1925, the confederalist movement in Yakutia was relatively peaceful. Only ten times during the entire time of the uprising there were skirmishes with Soviet units, serious battles did not follow. The leadership of Soviet Yakutia tried to resolve the conflict situation peacefully and offered Ksenofont's amnesty to him personally, to all leaders and participants in the movement in exchange for laying down arms. Ultimately, Ksenofontov, convinced that main task party is a statement about existing problems and its point of view on their solution, January 1, 1928 laid down his arms. A number of his supporters preferred to “run” with weapons for some more time, but on February 6, 1928, the last rebels capitulated. Although the uprising as a whole did not have a serious scale, and its leaders agreed to voluntary surrender, the Soviet leadership violated the promises of an amnesty.

Ksenofontov and other leaders of the uprising were arrested. On March 27, 1928, the Troika of the OGPU sentenced Pavel Ksenofontov to death, and the next day, March 28, 1928, he was shot. Mikhail Artemyev was shot on March 27, 1928 by the verdict of the Troika. The total number of those arrested in the case of the Ksenofontov uprising was 272 people, of which 128 people were shot, 130 were sentenced to various terms of imprisonment and the rest were released. At the same time, the purges also affected the leadership of the Yakut Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, which, in the opinion of the central authorities, could not bring full order to the territory of the republic. In particular, the chairman of the CEC of Yakutia, Maxim Ammosov, and the secretary of the Yakut regional party committee, Isidor Barakhov, were removed from their posts.

The confederalist uprising is one of the most famous examples of organized resistance to Soviet power and its policies in Yakutia. But even later, in the 1930s, there were numerous actions of the indigenous population of Eastern Siberia and the Far East against the Soviet regime. Local residents were not satisfied with the results of collectivization, they were not satisfied with the policy of the Soviet government, aimed at eliminating traditional religious cults and the usual way of life. On the other hand, the Soviet government, in suppressing such speeches, acted more and more harshly, since the increasingly difficult situation in the country and in the world required increased attention to the observance of the national security interests of the state. Moreover, in the immediate vicinity of Soviet Siberia and the Far East, on the territory of Korea, Manchuria, Inner Mongolia, hostile Japan was actively operating, striving to establish hegemony in the entire Asia-Pacific region.

The People's Army consisted of the Northern Volunteer Group, commanded by Oshiversky, who arrived from Okhotsk, the Lena Volunteer Detachment and the Left Bank Vanguard Group. The Northern Volunteer Group included three companies with a total of up to 300 mounted soldiers. The commander of the 1st company was Lieutenant Protasov, the 2nd company - Lieutenant Semenov. The Left Bank avant-garde group included 320 cavalry fighters, led by N.F. Dmitriev. The Lena Volunteer Detachment consisted of 440 fighters led by the cornet Kharkov, the chief of staff was A. Ryazansky. The detachment included 3 small detachments:

1 detachment - 200 mounted fighters under the command of Lebedev;

2 squad - 180 cavalry fighters under the command of Kharlampiev;

3rd detachment - 80 equestrian fighters under the command of the cornet A. Ryazansky.

In total, the people's army operating near Yakutsk consisted of 1000 - 1200 fighters. The northern anti-Bolshevik detachment, operating in the Verkhoyansk and Kolyma districts, numbered 100-200 people. In the Vilyui district, there were about 300 fighters from six partisan detachments, which merged into one "Southern Anti-Bolshevik Detachment" under the command of P.T. Pavlova. All anti-Bolshevik detachments had among themselves good communication and, although the Bochkarev officers of the northern anti-Bolshevik detachment did not recognize the VYaONA, they also kept in touch with Okhotsk. They had 2 infirmaries, where the wounded were treated by two doctors and 7 sisters. There were 25 Russian officers in the people's army, in total there were 80 Russian people.

They were armed with three-line rifles, the main armament was hunting berdans with 30 rounds of ammunition for each fighter and 4 light machine guns (3 Shosh, 1 Colt). The officers wore military uniforms, the rank and file of the rebels had epaulettes with company numbers and emblems on the sleeves.

Shoulder straps of the Yakut people's army. No. 1 - an officer's epaulette cut out of church vestments; No. 2 - shoulder strap of an ordinary Lena volunteer detachment (which was part of the 1st Yakut partisan detachment); No. 3 - epaulette of a private of the Northern Volunteer Group (2nd company); No. 4 - epaulette of an ordinary Southern anti-Bolshevik detachment.

Vishnevsky E.K. Argonauts of the White Dream Description of the Yakut Campaign of the Siberian Volunteer Squad. Harbin, 1933. http://lib.rus.ec/b/232061/read#t26

The following units were formed: three battalions of riflemen, a separate cavalry battalion, a separate battery, a separate engineer platoon and an instructor company.

Upon arrival in Ayan, a commissariat was formed. Lieutenant Colonel Maltsev was appointed quartermaster. In the village of Nelkan, the post of head of supply and head of logistics was established, to which position Colonel Shnaperman was appointed, with the rights of assistant commander of the squad for the economic part; A. G. Sobolev was appointed his supply assistant.

The squad in Vladivostok was supplied with food for 4–5 months, winter uniforms (short coats, felt boots and hats) for only 400 people, summer uniforms for the entire squad.

Distinctive signs and epaulettes of the ranks of the Siberian Volunteer Squad.

Three well-known photographs of the Pepelyaev detachment, published in the book “Yakutia. Historical and Cultural Atlas” (M.: Feoriya, 2007, pp. 357-368), as well as on the website: http://natpopova.livejournal.com/353326.html?page=1 it can be seen that all the ranks wear shoulder straps, and some of them clearly distinguish between white piping, white gaps for officers and white basons for non-commissioned officers. Given the initial desire of A.N. Pepelyaev to completely abolish shoulder straps and their subsequent preservation under pressure from colleagues, it is logical to assume that only their protective version was used in the squad.

The same with cockades: according to the literature, after the start of the expedition they were replaced by white-green ribbons, however, in the photographs mentioned above, taken in the autumn of 1922 in Ayan, cockades on caps are clearly distinguishable by their characteristic oval. Presumably, here too A.N. Pepelyaev had to compromise, returning to the version intertwined with a white and green ribbon.

A white and green armband with a militia cross is supposedly a distinctive symbol of the 3rd battalion of the Druzhina, formed from the remnants of the Yakut rebel detachments. The cross is made in the application technique, the encryption is drawn with an indelible pencil. The original armband is kept in the Museum of Anti-Bolshevik Resistance in Podolsk.

It was planned, after landing on the coast of the Sea of Okhotsk, to occupy Yakutsk, joining the forces of the rebels, to capture Irkutsk, form the Provisional Siberian Government there and start preparing for the elections to the Constituent Assembly. Taking into account the mood of the Yakuts and Siberians in general, Pepelyaev decided not to speak under the white-blue-red Russian flag, but the white-green Siberian flag of the Siberian autonomy that existed in 1918. The detachment, called the "Police of the Tatar Strait", received 1.4 thousand rifles. different pattern, 2 machine guns, 175 thousand rounds of ammunition and 9800 hand grenades. Warm uniforms were received in Vladivostok, partly bought by representatives of the Yakut authorities. The core of the detachment was the 1st Siberian Rifle Regiment under the command of Major General Evgeny Vishnevsky. Many Siberian volunteers began to enter the detachment: officers and shooters. From Primorye, the detachment included 493 people, from Harbin - 227. Three battalions of riflemen, a separate cavalry division, a separate battery, a separate engineer platoon and an instructor company were formed. Battalions and companies were commanded by colonels and lieutenant colonels, as young as their commander.

Figures 1 and 2 - officers of the Siberian volunteer squad; figure 3 - a Yakut rebel in national clothes and with an armband; figure 4 - an officer of the Yakut People's Army (for the period of his stay in the Druzhina), dressed in a fur Yakut kukhlyanka and a fur hat with earflaps purchased on the coast.

Yuzefovich L.A. General A.N. Pepelyaev and anarchist I.Ya. Strode in Yakutia. 1922- 1923. M., 2015.

P. 49. Korobeinikov coordinated with the headquarters the actions of individual detachments, headed by white officers. Yakut commanders were awarded officer ranks. The son of the Amga toion, Afanasy of Ryazan, promoted by Korobeinikov to ensign, tailored his shoulder straps from church robes embroidered with gold.

P. 78. In order to solder the volunteers with an inspiring sense of equality, Pepelyaev wanted to abolish shoulder straps, but the officers were indignant, and he had to retreat. The protest was led by Colonel Arkady Seifulin. A nobleman, for some reason he ended up on the German front as a private and, according to Pepelyaev, served his colonel's rank with the blood of 27 wounds. For people like Seifulin, who worked hard to earn their living in the artels created by Pepelyaev, officer epaulettes remained the only clear confirmation of their success in life.

P. 81. Half of the detachment received winter uniforms, but Pepelyaev was eager to sail to Ayan as soon as possible. He hoped to capture Yakutsk before the onset of frost.

pp. 85-86. In an upbeat atmosphere that usually accompanies the beginning of a voyage, the ships read out an order to rename the Northern Territory Militia into the Siberian Volunteer Squad. After that, the cockades on the caps were replaced with white and green ribbons - the old hallmark of the Siberian army.

P. 134. (August 1922, Ayan) ... He wrote to Kulikovsky something else: “People are hungry, lightly dressed and barefoot. From shoes - a hundred pairs of ichig, you have to wrap your feet in skins.

P. 138. (September 1922, Ayan, from a letter from Pepelyaev to his wife) Winter clothes arrived from Ayan yesterday, and now they are distributing: mittens, warm underwear, and fur hats are being distributed. The coats haven't arrived yet. Here we will get everything, we will dig up food, Vishnevsky will come up - and we will move on.

P. 166. Loneliness, lostness - everyone felt it. The new situation demanded new relations between people, and in its New Year In an order, Pepelyaev prescribed in a special clause: from January 1, 1923, “to consolidate the cohesion” of the squad, when referring to each other, use the word “brother” before the rank - brother-volunteer, brother-colonel, brother-general ... The innovation quickly took root, although at first it was approved not all officers.

P. 175. (Yakut rebel detachments). Soon... an unknown rider arrived. “Having tied a horse in the yard,” Strod recalled, “he went into the yurt, took off his old, with shabby wool, a short deer coat. On his tunic he had epaulettes, on which it was written with an indelible pencil: 1. Ya.P.O., that is, "1st Yakut partisan detachment."

P. 181. From Amga, after talking with Baikalov on the phone, Strod sent Vychuzhanin and Nakha to him and an inadvertently captured Pepelyaev man in a tunic with soldier epaulettes, on which everything that is usually present in the form of stencils or stripes was drawn in a student way and written with chemical pencil.

P. 214 (Defense of Sasyl-Sysy). At the table sat five in clothes without shoulder straps. When asked which of them Pepelyaev, the sixth responded, whom the parliamentarians did not notice at first ... He was wearing reindeer skins (fur stockings) and a “knitted red sweatshirt” of clearly domestic origin.

P. 228. There were no shamans at the headquarters of the Siberian squad, Pepelyaev did not turn to them for predictions, as Ungern did to the Mongolian lamas. He barely knew a dozen Yakut words, did not try to introduce national symbols into military uniforms or put emblems of national symbols on the banners, had no idea about Yakut mythology and did not appeal to it in his manifestos. He was disgusted by any ideological eccentric ...

pp. 241-242. (Defense of Sasyl-Sysy, the presence of legible insignia on the form). The non-commissioned officer, having received a mortal wound in the temple, fell face down in the snow ... Near the Colt machine gun lies the huge clumsy body of the Pepelyaev sergeant major ...

P. 265. (The Capture of Amga by the Reds). Its garrison consisted mainly of officers. Many fired back to the end and only in a hopeless situation raised the rifle with the butt up. It meant a willingness to surrender. Attempts to deal with them were thwarted, but three Red Army soldiers were killed right on the spot, who were captured, joined the Siberian squad and did not have time to tear off the white-green ribbon from their hats. The fierceness of the battle was vented on the unfortunate "traitors".

Strod I.Ya. In the Yakut taiga. M., Military Publishing, 1961// http://libatriam.net/book/922068

On the Second River, seven miles from Vladivostok, where the Pepelyaevs who came from Harbin were housed in the barracks assigned to them, Pepelyaev’s former colleagues from other places began to flock, as well as the White Guards who had fled from the ranks of the coastal army. Soon a detachment of 750 people, half of the officers, gathered there. According to the general's plan, such a large number of officers was needed for the future "people's army", which he dreamed of deploying from the one who rebelled against Soviet power kulaks. For the purposes of conspiracy, the detachment was formed under the guise of the militia of the Northern Region.

The leader of the Siberian regionalists, Narodnaya Volya member Sazonov, "the grandfather of the Siberian counter-revolution", who managed to get close to the Japanese general Fukuda, tried to lead Pepelyaev's speech, but the general rejected these encroachments. Nevertheless, he made a concession to the regionalists, allowing him to organize an information department for work among the population at the Yakut expedition. As a sign of ideological solidarity, the white and green banner was recognized as a symbol of Siberian autonomy. Pepelyaev, in turn, ordered his detachment to wear white and green ribbons instead of cockades. And before sailing to Yakutia, in an order to the personnel, he definitely expressed his regional aspirations in relation to Siberia.

At the beginning of the formation of the squad in Harbin and Vladivostok, Pepelyaev proposed to cancel shoulder straps. He thought by this to achieve a semblance of democracy and difference from the old army. For the most part, the officers were against this innovation. Pepelyaev had to come to terms with shoulder straps. Before the occupation of Amga, Pepelyaev tried to "democratize" his squad from the other end. He issued a long order, in which he declined the word "people" in all cases, ordered to call each other "brothers", not forgetting, however, the ranks.

In Ayan, from the remnants of the ingloriously ended "Yakut people's army", the White Guards formed the 3rd separate Yakut battalion of about two hundred people. Under the leadership of several Pepelyaev officers, the battalion began intensive military training.

In the afternoon, an unknown armed rider arrived. Having tied his horse in the yard, he went into the yurt, took off his old, with shabby wool, a short deer coat. There were epaulettes on his tunic. The White who arrived was very surprised when he realized that there were Reds in the yurt. He said that he was sent to the Amginsky district with Pepelyaev's appeal and is now returning.

Having received such a report, Vishnevsky ordered his chains to quickly move forward, surround the yurts, and take the fighters prisoner. Ten minutes later, a hundred white people approached the yurts. Some of them remained in the yard and began to examine the cargo in our convoy. Groups of ten people entered the yurts. There, they first threw firewood into the fire and only then began to wake up their captives.

The red fighters stirred, the commanders woke up and began to rub their eyes in surprise:

What the hell is this! What kind of people? Uh, yes, they have shoulder straps!

They grabbed their rifles, but it was too late.

Drop your weapon, don't move! You are surrounded and all resistance is useless! We won't do anything to you. It's good that everything ended without bloodshed. Let's smoke, we have Harbin tobacco, first-class. Want to?

The door creaked, and the colonel came into the yurt together with puffs of cold air. The conversations were silent. Having glanced at the inside of the yurt and lingered for a few seconds on the prisoners, the colonel turned to his subordinates:

Brothers! Shooting started on the right. Four people stay here, and the rest go out into the yard.

Returning from the pursuit of the whites, the first squadron made its way through the bushes and stumbled upon the motionless body of the colonel. At first they thought he was dead. Came closer, looked closely - breathes. It turns out that the colonel is wounded and lies unconscious. They took it with them, brought it to the yurt and put it in a corner on the hay. A few minutes later, the released orderly asked the Red Army men to bring the wounded closer to the fire. They took off the doha, unbuttoned the jacket - the shirt was covered in blood.

With a creak, the door to the yurt opened. Behind the cloud of frosty air that rushed in, it was immediately impossible to make out the newcomer, who silently approached the fire and only then spoke:

I'm cold, let me warm up!

They gave him a seat. The newcomer, of enormous height and powerful build, was dressed in wide trousers and a jacket made of gray overcoat. He didn't have a fur coat or a sheepskin coat. From the epaulettes on the jacket, it was not difficult to determine that this was a sergeant major.

Only in the yurt the bandages were removed from the parliamentarians. At the table they saw about five officers - obviously headquarters.

Which one of you is General Pepelyaev? Volkov asked.

I,” answered a tall black-bearded man standing by the crackling fire. He was wearing cloth trousers, reindeer camuses, a knitted red sweatshirt without shoulder straps.

The early morning silence was broken by the warning shot of our machine guns. Towards the white trench rumbled with a fiery flash of a volley. Then a fractional dissonance of shots began. People walking in front, dressed in sheepskin coats, were falling, and others were replacing them. The forest edge threw more and more chains onto Lisya Polyana. Ignoring the losses, leaving the dead and wounded behind them, the whites climbed aggressively, urged on and encouraged by the officers.

90 years ago, the Tungus and Yakuts turned to the League of Nations with a request to save them from communismArticle by Arman Marashetsi with my abbreviations, editing and additions.

Exactly 90 years ago, on February 13, 1925, a forgotten historical event took place - a major battle between the Tunguska rebels and the Soviet authorities. The armed uprising of the indigenous peoples of the North under the leadership of the Yakut Mikhail Artemiev and the Tungus Pavel Karamzin went down in history as the "Tunguska uprising" and swept through the years 1924-1928. all the Okhotsk coast and the eastern regions of Yakutia.

On the left photo - Mikhail Artemyev. On the right - a group of commanders of the Tunguska detachments ( P.G. Karamzin - second from the left in the top row). The biography of Pavel Gavrilovich Karamzin is almost unknown. However, few surviving documents indicate that he came from an Evenk princely family, presumably from the Ayano-Maisky district of the Khabarovsk Territory.

This uprising of the Yakuts and Tungus (Evenks) against the Soviet regime was by no means the first.

Back in 1921, an uprising broke out in the Ayano-Maisky district. The uprising was led by the Yakut G.V. Efimov, but Russian White Guards also took part in it under the leadership of the cornet Mikhail Korobeinikov. The rebels organized the Yakut Regional Administration, the Yakut rebel army was created. In 1922, the YAO applied asking for helpto the Merkulov brothers, who ruled in Vladivostok (until October 1922, Primorsky Krai was the last enclave of Russia not conquered by the Bolsheviks), but they did not receive help. However, whenThe Merkulovs were deposed by General M.K. Yakutia also had access to the Sea of Okhotsk).

Generals M. Dietrichs (left) and A. Pepelyaev (right)

After landing, the Pepelyaev detachment went to Yakutsk. As a result of his defeat in March 1923, Pepelyaev was forced to retreat towards the coast. In the summer of 1923, Pepelyaev was defeated. Only parts of his army, led by Colonels Sivkov, Anders, Stepan and Leonov, survived. Part of the army (230 soldiers and 103 officers), led by Pepelyaev, surrendered.

In addition to the detachment of Pepelyaev, since 1920, an insurgent detachment led by Captain Yanygin was in Okhotsk. In 1921, reinforcements came to them - a detachment of Bochkarev that arrived from Vladivostok. In the fall of 1922, the arrival of General Vasily Rakitin took over the leadership of the detachment. In the same year, Rakitin's detachment went to Yakutsk, with the exception of Captain Mikhailovsky's detachment, which remained in the city. In the summer of that year, Okhotsk fell. Yanygin managed to escape, General Rakitin died.

Now back to the Tunguska uprising of 1924-1925.

The main reasons for the uprising are considered to be the separation of the Okhotsk Territory from Yakutia in April 1922 with the transfer to the Primorsky and Kamchatka regions, as well as the closure of ports for foreign trade, interruptions in the importation of goods from the mainland, the confiscation of deer from private owners, the seizure of vast pastures for industrial new buildings and other arbitrariness of the Soviet authorities. On the coast of Okhotsk, the local OGPU terrorized the local population, forcing them to pay exorbitant taxes, shamelessly robbing literally everything: for game, weapons, firewood, dogs, peeled tree bark, etc. Things got to the point that they began to take the old debts established by the White Guards in 1919-1923. In addition, representatives of the Soviet government did not know the language of the Tungus, life, customs. There were no national schools, there was not a single native in the state institutions.

In May 1924, the rebels under the leadership of M.K. Artemiev occupied the village of Nelkan. On June 6, 60 rebels captured the port of Ayan after an 18-hour battle. During the battle, the head of the OGPU, Suvorov, and three Red Army soldiers were killed, and the surrendered garrison was released by the Tungus and sent to Yakutia.

A congress of the Ayan-Nelkan, Okhotsk-Ayan and Maimakan Tunguses and Yakuts was convened in Nelkan. It elected the Provisional Central Tunguska National Administration, which decided to secede from Soviet Russia and form an independent state. M.K. Artemyev was elected chief of staff of the armed detachments, and P. Karamzin was appointed head of all the Tungus detachments.

On July 14, 1924, the All-Tungus congress of the Okhotsk coast with adjacent areas was held in Ayan, declaring the independence of the Tungus people and the inviolability of its territory with sea, forest, mountain riches and resources. The leaders of the movement of different nationalities M.K. Artemyev, P. Karamzin, S. Kanin, I. Koshelev, G.Ya. Fedorov and others, 10 people in all, compiled an “Appeal” to the world community. It talked about the fact that the Tungus, backward “in all respects from the world progress of science and technology”, turn to foreign states and the League of Nations, “as to powerful defenders of small nationalities on a global scale” on the issue of saving them from the “common enemy of the world nationalism - Russian communism.

Flag of the Tunguska Republic

The rebels created the attributes of their national-territorial formation. They adopted the tricolor flag of the “Tunguska Republic”: white symbolized the Siberian snow, green - the forest, taiga, black - the earth. It also adopted its own anthem.

All this refutes the assertions of Soviet authors that the named uprising was criminal. The leaders of the uprising were political oppositionists who rallied around specific socio-political ideas. The rebel leadership was well acquainted with legislative and philosophical sources.

This is evidenced by their demands for national self-determination, individual rights, the rights of small ethnic groups, the creation of an independent national-territorial entity, and so on. The reason for the dissatisfaction of the rebels was the inequality of the rights of large and small peoples in the creation of a national-territorial federation.

Tungus, being under the authority of the authorized V.A. Abramov, experienced the policy of terror of the “war communism” era. In addition to political demands, the rebels put forward demands of an economic and cultural nature. For example, they suggested restoring the old routes: Yakutsk - Okhotsk, Nelkan - Ayan and Nelkan - Ust-Maya. That is, they sought to establish former economic ties with Yakutia. In addition, a set of measures was developed for the economic and cultural development of the Okhotsk coast zone.

The Provisional Central Tunguska National Directorate warned the Central Executive Committee of the USSR that: “In the event of the landing of military units of Soviet troops on our shores of the Sea of \u200b\u200bOkhotsk and an invasion through the borders of the neighboring republics of the Far East and the Yakut autonomy, we, the Tunguska nation, as completely rebelled because of intolerant the politicians of the Bolsheviks will have to offer armed resistance as proof of our deep indignation and we will be sure that for the possible victims, all responsibility for the shed innocent blood before history and public opinion will fall on you as the highest organ of Soviet power, which allowed violence. Consequently, the participants in the movement did not at all want bloodshed and wanted to resolve the urgent conflict through peaceful negotiations. This is also evidenced by the facts of the release of captured Red Army soldiers and Soviet employees.

The immediate reason for the uprising was the execution in September 1924 by a detachment of the Okhotsk OGPU near the village of Ulya of three Russian fishermen, two Tungus and one Yakut. In response, armed self-defense units began to organize everywhere. According to various studies, the M.K. Artemyeva without a fight took possession located 315 km. from Yakutsk by the village of Petropavlovsk, Ust-Maisky district. At the same time, pockets of rebellion in the North of the Yakut Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic became more active: Oymyakonsky, Verkhoyansk, Abyisky (Elgetsky) and other uluses. On December 31, 1924, the rebels captured the settlement of Arka, and then New Ustye, located 7 km. from Okhotsk. A group of rebels under the command of G. Rakhmatullin-Bossooyka rushed to Nelkan. Mikhailov's detachment of 40 people went to the East Kangalassky ulus, reading appeals to the people in the Yakut and Russian languages at rural gatherings.

On August 10, a congress of the Tungus of the Okhotsk coast opened in Okhotsk, which was attended by representatives of 21 Tungus clans and three Yakut regions. They adopted a resolution on trade, hunting and fishing, health care, and public education. Particular attention was paid to the organization of tribal Soviets. The Tunguska Congress, through a peaceful delegation, submitted to the Central Executive Committee of Yakutia the requirements for:

1) the separation of the Okhotsk coast from the Far East and its reunification with Yakutia;

2) granting the right to the Tungus themselves to resolve political, economic and cultural issues;

3) removal from power of the communists who pursued a policy of terror.

In order to fight the rebels, the III Extraordinary Session of the Yakut Central Executive Committee was convened. On it, the secretary of the regional committee Baikalov K.K., the rebels were called bandits, and their leaders - "elements drugged by the illusion."