On my own indefinite article in English language(the Indefinite Article) serves to designate the category of uncertainty and is used only with singular countable nouns. The indefiniteness caused by the indefinite article in English has the meaning of “some, unknown what.” Indefinite articles in English indicate that an object belongs to some class of objects and carry a classifying meaning:

- This is a cat. - It's a cat. (Unknown which one, one of the cats)

The history of the origin of the indefinite article in English

As for the history of the origin of the indefinite article a (an), it is believed that it came from the Old English word ān, i.e. “one” (one):

- A coffee, please. - One coffee, please.

- Wait a minute. - Wait one minute.

Using the indefinite article in English

The indefinite article in English has two forms - a and an. Form a is used before words beginning with a consonant: a tree (tree), a song, a finger (finger); the form an, in turn, is used before words starting with a vowel sound: an apple (apple), an elephant, an owl (owl).

Thus, the indefinite article is used in the following cases:

- When we are talking about an object or a person as a representative of a particular class. Often this noun comes with an adjective that describes it. For example: It was a very interesting story.- It was very interesting story. This is a pupil. He is a very good pupil.- He's a student. He is a very good student.

- This type of article is used with singular nouns in constructions there is/ was/ will be, have (got), this is… For example: There is a table in the room. — There is a table in the room. This is a nice house. - This is a beautiful house.

- When we mean everyone, any representative of a given class, the indefinite article is also used. For example: A baby can understand it. “Any child can understand this.”

- When we are talking about an object or person unknown to the interlocutor, that is, this word is used in the text for the first time. For example: We saw a man in a dark coat. The man was holding a stick.— We saw a man in a dark coat. The man was carrying a cane.

- In exclamatory sentences. For example: What a nice surprise! - What a pleasant surprise!

- With the words “one hundred”, “thousand”, “million”, etc., meaning “one”. For example: a (one) hundred, a (one) thousend, a (one) million, etc.

- In expressions such as per day, per hour, per year etc. For example: He calls his parents three times a day.— He calls his parents three times a day. We have four English classes a week.— We have four English lessons a week.

- With singular countable nouns with words such, quite, rather. For example: It was such a sunny day! — It was such a sunny day! He is quite a tall boy for his age.— He is quite a tall boy for his age. She is rather a good cook. — She's a pretty good cook.

- With uncountable nouns meaning "portion". For example: Would you like an ice-cream? -Will you have some ice cream?

- With proper names meaning “some”, “some”. For example: I started working for a Mr. Rochester, but I haven’t seen him yet.“I started working for a certain Mr. Rochester, but I haven’t met him yet.”

- With proper names meaning “one of”, “representative of a family or clan”. For example: It was met by a Burton. “I was met by one of the Burtons.”

- With proper names meaning “work of art” (for example, a painting, a sculpture, a piece of music). For example: I sold him a Coin. — I sold him a Monet painting.

Thus, dear friends, indefinite article in English corresponds to the category of uncertainty and the meaning “one”, which one way or another we have to use both in writing and in speech in English.

Full-valued verbs usually act in a sentence as a predicate or a semantic part of the predicate. The vast majority of German verbs fall into this category.

Functional verbs are used in a sentence in combination with other verbs, being only part of the predicate. In this case, they usually lose (partially or completely) their independent semantic meaning.

- Function verbs in German include:

- auxiliary verbs - haben, sein, werden;

- linking verbs - sein, werden, bleiben, heißen.

Using the auxiliary verbs haben, sein, werden, complex tense forms and passive voice are formed.

- The verbs haben, sein can also be used as full verbs. In this case, these verbs are translated into Russian:

- haben- have:

- sein- to be, to be:

- Modal verbs differ from ordinary full-valued verbs. They express not an action, but an attitude towards action. Modal verbs can express possibility, necessity, desire. Modal verbs in German include the following verbs:

- mussen- must, be obliged, be forced.

The verb müssen expresses necessity due to internal conviction, duty.

- sollen- must, be obliged.

The verb expresses necessity, obligation, obligation associated with someone’s instructions, the order established by someone, etc.

The verbs müssen and sollen can also be used to express an assumption, with the verb müssen to express one’s own assumption, and the verb sollen to express an assumption arising from someone else’s words.

- können- be able, be able (to have the physical ability to do something):

The verb können can also be used to mean “to be able to”:

- wollen- want, desire (often with a connotation of “intend to do something”):

The verb wollen is also used in the descriptive form of the 1st person imperative.

The verb mögen can also express a wish, advice, recommendation and is often translated in this case with the word “let”.

In this step we will get acquainted with another group of verbs - modal verbs in German. We are talking about verbs that express a subjective attitude to a situation, for example I can do something, I want to do something etc. They conjugate in an unusual way. These are the verbs:

können- be able to, be able to

wissen- know

mussen- to be due

sollen- to be due

mögen- be in love

möchten– would like (derived from the verb mögen, meaning “I would like...”)

wollen- want

durfen– allow (meaning “I am allowed...”)

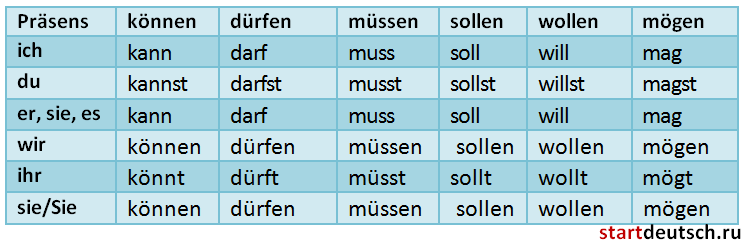

Modal verbs in German are conjugated as follows:

| ich | kann | wir | können |

| du | kannst | ihr | könnt |

| er/sie/es | kann | Sie/sie | können |

Actually, the whole feature lies in the first column. Here können is turning kann And kannst. In the second column, the verb receives endings that are already known to us; there is nothing new. In addition, the forms ich And er match up. Therefore, for the remaining modal verbs I will give only the first column:

| wollen | wissen | durfen | mögen | möchten | sollen | mussen | |

| ich | will | weiss | darf | mag | möchte | soll | muss |

| du | willst | weisst | darfst | magst | möchtest | sollst | must |

| er/sie/es | will | weiss | darf | mag | möchte | soll | muss |

Now let’s bring these verbs into our conversation and analyze their meanings in detail.

können- be able, be able (general meaning). By using können can be expressed:

ability : Ich kann schwimmen. - I can swim.

opportunity : Hier kann man schwimmen. - You can swim here.

permission : Du kannst heute Nacht bei uns bleiben. “You can stay with us tonight.”

polite question: Kann ich Ihnen helfen? - Can I help you?

durfen- to have permission to do something. Also durfen has the following meanings:

permission: Sie dürfen gern hereinkommen. - You can come in.

to have a right: Mit 18 Jahren darf man in Deutschland wählen. — In Germany, people over 18 years of age have the right to vote.

polite question: Darf ich Sie etwas Persönliches fragen? — Can I ask you something personal?

moral: Man darf nicht zu alten Leuten unhöflich sein. “You can’t be impolite with older people.”

What is the difference between durfen And können in polite questions? Dürfen- this is a more polite form, können– more informal.

mussen- to be due (subjective feeling or intention). By using mussen can be expressed:

call of Duty: Ich muss für die Prüfung lernen.— I have to study for the exam.

moral: Man muss alten Leuten helfen.— We need to help older people.

duty before the law

: Bei einer roten Ampel muss man warten.— If the traffic light is red, you need to wait.

sollen- to be due (objective feeling, that is, someone else said that he should). This word can be expressed:

objective duty

: Der Lehrer hat gesagt, ich soll nach dem Unterricht bleiben.— The teacher said that I should stay after class.

recommendation: Du bist erkältet, du sollst lieber zu Hause bleiben.- You have a cold, you better stay home.

direct order: Sie sollen aufstehen!- You must get up!

question-suggestion

: Soll ich das Licht ausmachen?— Should I turn off the light? Soll ich dir helfen?- Should I help you?

mussen vs. sollen

Both words mean “to ought,” but the meaning is slightly different for both words.

Was denkst du? Soll ich heute tanzen gehen?- Do you think I should go to the dance today?

A very typical German answer:

Du kannst es gerne machen, aber du musst nicht.- You can do it (if you want), but you don’t have to (shouldn’t).

mussen– you yourself decided that you need to do this, it’s your will.

sollen– someone told you that you have to do this – it’s not your will.

wollen- want, desire, plan

Wir wollen Deutsch lernen.— We want to learn German.

Wollt ihr Deutsch lernen?— Where do you want/plan to learn German?

möchten- I would like to. A more polite form than wollen.

Möchten Sie auch etwas essen?— Verbatim: Would you also like to eat something?

Was it möchten Sie?—What would you like? (this is what the waiter asks in a restaurant)

Ich möchte nur trinken. - I would just like to have a drink.

mögen- to love, to like. This word has the following meanings:

be in love: Ich mag germn Eis.- I like ice cream. Ich mag nicht alleine zu Hause sein.— I don’t like being alone at home.

polite question "could you"

:Magst du diesen Text vorlesen?— Could you read this text out loud?

wissen- know

Er weiss das.- He knows it.

Weiss du, wann der Zug abfährt?— Do you know when the train leaves?

Ich weiss es nicht.- I don't know.

Modal verbs in German: expressing the degree of probability

Verbs müssen, sollen, können, mögen They are also combined into one group because they indicate different degrees of probability or confidence in such sentences as:

Das muss so sein.— That’s how it should be (I’m 100% sure)

Das soll so sein.- That’s how it should be (80% sure, because someone else said it)

Das kann so sein.— It may be so (I’m 50-60% sure, I don’t know for sure)

Das mag so sein.— Maybe so (I’m 30-40% sure, maybe, but I really doubt it)

Exercises for the topic:

Do you have any questions about this topic? Write in the comments.

Details Category: German modal verbsModal verbs express not the action itself, but the attitude towards the action (i.e. the possibility, necessity, desirability of performing the action), therefore they are usually used in a sentence with the infinitive of another verb expressing the action.

Modal verbs include the following verbs:

können dürfen müssen sollen mögen wollen

The conjugated modal verb stands In second place in a sentence, and the infinitive of the semantic verb is last in a sentence and is used without the particle zu.

können- be able, be able, be able (possibility due to objective circumstances)

durfen- 1) be able - dare, have permission (possibility based on “someone else’s will”) 2) when denied, expresses prohibition - “impossible”, “not allowed”

mussen- 1) obligation, necessity, need, conscious duty 2) when negated, “müssen” is often replaced by the verb “brauchen + zu Infinitiv)

sollen- 1) obligation based on “someone else’s will” - order, instruction, instruction 2) in a question (direct or indirect) is not translated (expresses “request for instructions, instructions”)

wollen- 1) want, intend, gather 2) invitation to joint action

mögen- 1) “would like” - in the form möchte (politely expressed desire in the present tense) 2) love, like - in its own meaning (when used without an accompanying infinitive)

The meaning of modal verbs in German

durfen

a) have permission or right

In diesem Park durfen Kinder spielen. - In this park for children allowed play.

b) prohibit (always in negative form)

Bei Rot darf man die Straße nothingüberqueren. - Street it is forbidden cross against the lights

können

a) have the opportunity

In einem Jahr können wir das Haus bestimmt teurer verkaufen. - In a year we will definitely we can sell the house for more money.

b) have the ability to do something

Er kann gut Tennis spielen. - He can play tennis well.

mögen

a) to have/not have an inclination, disposition towards something.

Ich mag mit dem neuen Kollegen nicht zusammenarbeiten. - I don't like work with someone new.

b) the same meaning, but the verb acts as a full-valued one

Ich mag keine Schlagsahne! - I don't I love whipped cream!

The modal verb mögen is most often used in the subjunctive form (conjunctive) möchte - would like. The personal endings for this form are the same as for other modal verbs in the present:

ich möchte, du möchtest, etc.

c) have a desire

Wir möchten ihn gern kennen lernen. - We would you like to meet him.

Ich möchte Deutsch sprechen.— I I would like to speak German.

Du möchtest Arzt werden. - You I would like to To become a doctor.

Er möchte auch commen. - He too I would like to come.

mussen

a) be forced to perform an action under the pressure of external circumstances

Mein Vater ist krank, ich muss nach Hause fahren. - My father is sick, I must to drive home.

b) to be forced to perform an action out of necessity

Nach dem Unfall mussten wir zu Fuß nach Hause gehen. - After the accident we must were walk home.

c) accept the inevitability of what happened

Das must ja so kommen, wir haben es geahnt. - This should have happen, we saw it coming.

d) Instead of müssen with negation there is = nicht brauchen + zu + Infinitiv

Mein Vater ist wieder gesund, ich brauche nicht nach Hause zu fahren. - My father is healthy again, I don’t need to to drive home.

sollen

a) require action to be performed in accordance with commandments, laws

Du sollst nicht toten. - You do not must kill.

b) demand the performance of an action in accordance with duty, morality

Jeder soll die Lebensart des anderen anerkennen. - Every must respect the other's way of life.

c) emphasize that the action is performed on someone’s order or instruction

Ich soll nüchtern zur Untersuchung kommen. Das hat der Arzt gesagt. - I must come on an empty stomach for the study. That's what the doctor said.

wollen

a) express a strong desire

Ich will dir die Wahrheit sagen. - I Want tell you the truth.

b) communicate your intention to do something, plans for the future

I'm December wollen wir in das neue Haus einziehen. - In December we we want move into a new house.

In some cases, the main verb may be omitted:

Ich muss nach Hause (gehen). Sie kann gut Englisch (sprechen). Er will in die Stadt (fahren). Ich mag keine Schlagsahne (essen).

A modal verb can be used without a main verb if the main verb is mentioned in the previous context:

Ich kann nicht gut kochen. Meine Mutter konnte es auch nicht. Wir haben es beide nicht gut gekonnt.

Conjugation of modal verbs

Conjugation tables for modal verbs need to be memorized.

Conjugation table for modal verbs in the present tense

Pronoun man in combination with modal verbs it is translated by impersonal constructions:

man kann - you can

man kann nicht - impossible, impossible

man darf - possible, allowed

man darf nicht - impossible, not allowed

man muss - necessary, necessary

man muss nicht - not necessary, not necessary

man soll - should, must

man soll nicht - should not

Conjugation table for modal verbs in the past tense Präteritum

Modal verbs in the past tense are most often used in Präteritum. In other past tenses, modal verbs are practically not used.

Place of a modal verb in a simple sentence

1. The modal verb is in a simple sentence In second place.

The second place in the sentence is occupied by the conjugated part of the predicate - the auxiliary verb haben. The modal verb is used in the infinitive and follows the full verb, occupying the last place in the sentence.

Präsens: Der Arbeiter will den Meister sprechen .

Präteritum: Der Arbeiter Wollte den Meister sprechen .

Perfect: Der Arbeiter hat den Meister sprechen wollen .

Plusquamperfect: Der Arbeiter hatte den Meister sprechen wollen .

Place of a modal verb in a subordinate clause

1. Modal verb in the form of present or imperfect stands in a subordinate clause last.

2. If a modal verb is used in perfect or plusquaperfect form, then it is also worth in the infinitive form in last place. The conjugated part of the predicate - the auxiliary verb - comes before both infinitives.

Präsens besuchen kann .

Präteritum: Es ist schade, dass er uns nicht be suchen konnte.

Perfect: Es ist schade, dass er uns nicht hat besuchen können.

Plusquamperfect: Es ist schade, dass er uns nicht hatte besuchen können.

In addition to ordinary, semantic verbs (I'm writing a book), denoting an action, so-called modal verbs also work in the verbal system, expressing the speaker’s attitude to the action, as well as the attitude of the action being spoken about to reality: I want, I can, I have to write a book. The book has not yet been written, in reality it does not exist, but there is my intention, the desire to write it.

Modal verbs usually appear in combination with semantic verbs, forming, as it were, one compound verb:

Ich muss jeden Tag zur Arbeit gehen. - I have to go to work every day.

Ich kann nicht jeden Tag zur Arbeit gehen. - I can’t go to work every day.

Ich will in Urlaub fahren. - I want to go on vacation.

The second verb goes to the end of the sentence. Sometimes it can be omitted altogether (since it is implied):

Ich muss zur Arbeit (gehen). - I need to go to work.

The conjugation of modal verbs has two features. Firstly, they have a special shape for singular. Therefore, this is what you need to remember: wollen (will) - want (want), müssen (muss) - be able (can) ... Secondly, in forms I And He There are no personal endings at all, and these forms are the same, coincide: ich muss - I must, er muss - he must (sie muss - she must). Compare with a regular semantic verb: ich trinke, er trinkt.

wollen (will):

ich will nach Hamburg fahren. (I want to go to Hamburg.) wir, sie, siewollen .

er (sie, es) will.

du willst.

Ihr Wollt.

So, modal verbs:

wollen (will) - want:

Wollen wir in die Stadt fahren? - Let's (literally: we want) to go to the city?

Das will ich doch nicht machen! - But I don’t want to do this!

müssen (muss) - to be forced, obliged (to do something):

Sie müssen vorher anrufen. - You must (you need) to call in advance.

Ich muss auf die Toilette. - I need (I have to) go to the toilet.

sollen (soll) - to be obliged, to (do something)(Only this verb has the same plural and singular forms):

Soll ich Sie vom Bahnhof abholen? - Should I meet you at the station (bring you, pick you up from the station?)

Der Arzt sagt, ich soll weniger rauchen. - The doctor says that I should smoke less.

konnen (kann) - be able, have the opportunity, be able to:

Können Sie mir helfen? - Can you help me?

Ich kann Auto fahren. - I can drive a car.

Hier stehe ich - ich kann nicht anders. (Martin Luther) - I stand on this and cannot do otherwise.

durfen (darf) - be able In terms of you can, you are allowed to do something:

Darf ich hier rauchen? - Can I smoke here?

Sie dürfen hier rauchen. - You can, you are allowed to smoke here.

mögen (mag) - be in love- In terms of: like(in this meaning the verb has almost ceased to be modal and is used independently, without another semantic verb); be possible:

Mögen Sie Eis? - Ja, ich mag es. - Do you like ice cream? - Yes I love.

Er mag Recht haben. - He's probably right.

Sie mag krank sein. - She may be sick.

Wie mag es sein? - How is this possible?

Instead of a verb wollen you can use a softer, more polite form möchten:

Ich will ins Theater. - I want to go to the theater.

Ich möchte ins Theater. - I would like to go to the theater.

Möchten Sie Tee trinken? - Would you like to have some tea?

Ich möchte ein Stück Kuchen. - I would like a piece of pie.

This form is conjugated as a modal verb with the only difference that in the forms I And he she it) it has an ending -e:

ich möchte, du möchtest, er möchte; wir möchten, ihr möchtet, sie möchten.

As you already know, verb wollen Can mean let's (do something):

Wollen wir heute Abend essen gehen! - Let's go to a restaurant today!

But, in addition, with the help wollen You can insist quite sharply on your own:

Willst du endlich einmal gehorchen! - You will finally obey!

Have you also noticed that mussen And sollen mean the same thing: to be obliged to do something. But they have different shades of meaning and differ in use. Sollen usually used when there is an indication of someone else's will: you have some kind of obligation to someone, someone gives you an assignment. Mussen it means the need to do something that you personally recognize; you yourself believe or understand that you need to do something. Compare:

Ich muss meine Wohnung renovieren. - I have to renovate the apartment. (These are the circumstances, nothing can be done, I am aware of this.)

Meine Frau sagt, ich soll die Wohnung renovieren. - My wife says that I should do some repairs. (Alien will.)

Herr Müller, Sie sollen bitte zum Chef kommen. - Mr. Muller, please come to the boss. (Chief's will.)

Sollen It is also used in a question when you ask someone else’s will:

Soll ich das Fenster aufmachen? - Open the window? Should I open the window?

Um wie viel Uhr soll ich Sie wecken? - What time should I wake you up?

And also when asking someone else's opinion:

Was soll ich tun? - What should I do?

Woher soll ich das wissen? - How do I know this?

Sollen can also convey what was heard from someone’s words (also, as it were, someone else’s opinion):

Es soll in Südfrankreich sehr warm sein. - It must be (they say, I heard) very hot in southern France.

In meaning let him do something sollen can be replaced with a more polite form möchten. Compare:

Sagen Sie ihm, er sollmichanrufen. - Tell him to call me (let him call).

Sagen Sie ihm, er möchte mich anrufen. - The same thing, but more politely.

Sollen you can also use when giving advice to someone:

Du sollst deine Oma besuchen! - You should visit your grandmother!

Although you are imposing your will on your interlocutor here, it still sounds softer than:

Du musst deinen Opa besuchen! - You should visit your grandfather! (You yourself understand that this is absolutely necessary)

There is a saying:

Muss ist eine harte Nuss! - Must be a hard nut to crack!

Verb können often used with an indefinite personal pronoun man:

Kann man hier telefonieren? - Ja, man kann. - Can I call here? - Yes, you can.

Ja, Sie können hier telefonieren. - Yes, you can call here.

In this case, we are talking more about the physical ability to call, about the presence or absence of a telephone. If you have a telephone and you ask permission, then it is better to use the verb durfen:

Darf ich hier telefonieren? - Can I call here?

Darf man hier fotografieren? - Can I take pictures here?

When answering, however, they often simply say You can, that is, it is not necessary to say You are allowed:

Sie können (dürfen) hier fotografieren.

Man darf hier fotografieren.

Können also means be able to:

Kannst du schwimmen? - You can swim?

Ich kann (kein) Deutsch. - I do not speak German.

I wonder what the meaning is man kann (possible) is also expressed using a special suffix (that is, an addition to the word) -bar:

Das ist machbar. = Das kann man machen. - It can be done, it is feasible, literally: doable.

Das Gerät ist reparierbar. = Man kann das Gerät reparieren. - This device can be repaired, it is “fixable”.

Das ist unvorstellbar! = Das kann man sich nicht vorstellen. - This cannot be imagined, it is “unimaginable”!

Germans don't speak I need..., they say instead I have to... (do something) or I need...:

Ich muss einkaufen. - I need (I must) to the store (literally: to purchase).

Ich brauche Entspannung. - I need rest (literally: relaxation).

When denying the need to do something, verb mussen often replaced by a verb brauchen (to need something):

Must du wirklich auf den Markt gehen? - Do you really have to go to the market?

Du brauchst heute nicht auf den Markt (zu) gehen. - You don't need to go to the market today.

From here it is easy to go to Imperative with negation, that is, to expressions like Don't do this!

Da brauchst du nicht (zu) lachen! - There’s no need to laugh here (at this)!

Ihr braucht keine Angst (zu) haben! - You don't need to be afraid, don't be afraid!

pay attention to zu. Important rule: a particle is always placed before the second verb in a sentence zu, if the first verb is not modal (as for the verb brauchen, then in this meaning it is so close to modal that it can do without a particle):

Es "ist" schwierig, viel Geld zu"verdienen". - It's hard to earn a lot of money.

Schwierig, viel Geld zu verdienen.(The first verb here is implied, invisibly present.)

And finally, this statement can be turned around:

Viel Geld zu verdienen, ist schwierig.(Wherein es- formal subject is no longer necessary.)

A few more examples:

Es wird immer leichter, Deutsch zu sprechen. - It is becoming increasingly easier to speak German.

Deutsch zu sprechen, wird immer leichter. - Speaking German is becoming easier and easier.

Ich versuche es, einen guten Job zu finden. - I’ll try (this), try to find a good job.(It's interesting here es- like a support for further statements).

Sie scheint uns nicht zu erkennen. - She doesn’t seem to recognize us (literally: she doesn’t seem to recognize us).

Er pflegt jeden Tag zu joggen. - He has the habit of going for a run every day.

Sie sucht immer ihren Freunden zu helfen. - She always tries (literally: seeks) to help her friends.

Der Entführer droht die Maschine in die Luft zu sprengen. - The hijacker threatens to blow up the plane (literally: blow it up into the air).

Here's an interesting case:

der Entschluss nach Amerika zu reisen - the decision to go to America.

There's only one verb here, but it's still necessary zu, since the word solution means action and replaces the corresponding verb:

sich entschließen, nach Amerika zu reisen - decide to go to America.

Pay attention to the turnover sein + Infinitive, which can mean two things. First, the possibility:

Die Ausstellung ist bis Ende Juni zu sehen. = Man kann diese Ausstellung bis Ende Juni sehen. - This exhibition can be viewed until the end of June.

Diese Frage ist schwierig zu beantworten. - This question is difficult to answer.

Er ist nirgends zu finden. - He can’t be found anywhere (i.e. he disappeared somewhere).

Von meinem Platz ist nichts zu sehen und zu hören. - From my place you can’t see or hear anything.

Die Reiselust der Deutschen ist nicht zu bremsen. - The desire of the Germans to travel cannot be slowed down (i.e. this desire knows no limit).

Secondly, obligation:

Diese Arbeit ist bis morgen zu machen. - This work must be done by tomorrow.

If we want to indicate who exactly should do this, then we need to use another phrase, namely haben + zu:

Sie haben diese Arbeit bis morgen zu machen. - You must do this work by tomorrow.

= Sie müssen diese Arbeit bis morgen machen.

Sie hat alle Hände voll zu tun. - She has a lot to do (literally: she has all her hands full of things to do).

This turn can also express the possibility:

Ich habe viel Interessantes zu erzählen. - I can tell you a lot of interesting things (I have something to tell).

But a combination is also possible haben + Infinitive, Where haben will not be used in the meaning to have to do something and in its usual meaning - have. Note that then zu no need:

Er hat Geld auf der Bank liegen. - His money is in the bank (literally: he has money in the bank).

Pay attention to three special turns with zu:

Er fährt nach Deutschland, um seine Freunde zu besuchen. - He is going to Germany to visit his friends.

Ich möchte in Urlaub fahren, ohne mich um meine Arbeit zu kümmern. - I want to go on vacation without worrying about work.

Sie geht, ohne sich zu verabschieden. - She leaves without saying goodbye.

Er sieht fern, (an)statt mir zu helfen. - He watches TV instead of helping me.

Similar phrases can be reversed, as in Russian:

Um uns zu amüsieren, gehen wir in den Zirkus. - To have fun, we go to the circus.