Individual and market demand is determined for each commodity price. But if the first indicator is the desires and capabilities of one buyer, then the second has a more voluminous meaning.

2. Market demand is a certain amount of a product that a certain number of buyers will acquire at a given price and at a given moment. That is, it is individual demand multiplied by the number of consumers whose capabilities and needs are satisfied by this product.

If we consider graphically the dependence of demand on the cost of goods, then the curve will have a stepped form. Each consumer has a sensitivity threshold. A gradual price reduction will not cause a stir and a sharp increase in demand. But if the cost of the goods becomes lower by a significant amount, then this will cause an increased interest of buyers.

But individual and market demand, in addition to cost, is influenced by other features. Among the main ones are the following:

1. The income of buyers, which determine its budget.

2. The cost of goods that can replace this product.

3. Buyers' preferences, which may change under the influence of certain events.

4. Number of consumers or market size.

5. Customer expectations.

Therefore, these factors may make the cost impact insignificant.

Consumer preferences can significantly affect the demand rate. This is the influence of fashion, national traditions, position in society and technological progress.

Demand depends on many factors. An individual indicator is considered in smaller economic formations. In the field of economics, within enterprises, companies and other large structures, market demand is considered.

1. Demand. The law of demand. Individual and market demand.

The main parameters of the market are: demand, supply, price. Demand is the defining parameter of the market, as it is based on the needs of people. The absence of needs determines the absence of not only demand, but also supply, i.e. no market relations at all.

However, people's needs are not demand. In order for a need to turn into demand, it is necessary that the manufacturer can actually satisfy it, i.e. produce a certain amount of material goods, and the buyer must have enough money to buy this product.

Demand - these are the needs of people in commodities and means of production that can be actually satisfied and provided in cash. It is expressed as a graph showing the amount of a product that consumers are willing to buy at a certain price from the prices that are possible over a certain period of time.

The fundamental property of demand is as follows: with all other parameters unchanged, a decrease in price leads to a corresponding increase in the quantity demanded. Conversely, ceteris paribus, an increase in price leads to a corresponding decrease in the quantity demanded. In other words, there is Feedback between price and quantity demanded. Economists call this feedbackLaw of demand . This law is based on the following facts:

A) common sense and elementary observation of reality. Usually people actually buy a given product more at a low price than at a high one. A high price discourages consumers from buying goods, while a low price increases their desire to buy.

B) In any given period of time, each purchaser of a product receives less satisfaction, or benefit, or utility, from each successive unit of the product. For example, the second chocolate bar eaten brings less pleasure than the first. It follows that since consumption is subject to the principle of diminishing marginal utility—that is, the principle that successive units of a given product bring less and less satisfaction—consumers buy additional units of a product only if its price falls.

C) Income and substitution effects. The income effect indicates that at a lower price, a person can afford to buy more of a given product without forgoing other goods. In other words, a decrease in the price of a product increases the purchasing power of the consumer's money income, and he becomes able and willing to buy more of the product at a lower price than at a high one.

The main factor influencing the magnitude of demand is the price. However, in addition to price, there are so-called non-price factors, the change of which shifts (in parallel) by some amount to the right or left of the demand curve. The most important of these factors include:

consumer tastes.

A favorable change in consumer tastes or preferences for a given product, caused by advertising or fashion changes, will mean that demand is increasing. Conversely, adverse changes will cause a decrease in demand.

Technological changes in the form of the emergence of a new product can also lead to a change in consumer demand. For example, the advent of CDs has led to a decrease in demand for long-playing records.

The number of buyers.

An increase in the number of consumers in the market causes an increase in demand, and vice versa, a decrease in the number of buyers leads to a decrease in demand.

For most goods, an increase in income leads to an increase in demand for them. Goods, the demand for which changes in direct connection with the change in money income, are called goods of the highest category, or normal goods.

But there are a number of goods, the demand for which changes in the opposite direction, that is, with an increase in income, the demand for such goods falls. They are called inferior goods.

In other words, with an increase in the income of the population, the demand for goods of higher quality, albeit at a slightly higher price, increases, and with a decrease in income, the demand for goods of lower quality, but cheaper, increases.

Prices for related products.

A change in demand due to a change in prices for related goods depends on whether these goods are interchangeable or complementary. A fungible good is a good whose use value is identical to that of another good. For example, butter is a substitute for margarine and vice versa. With an increase in the price of one of them (butter), the demand for a substitute product (margarine) immediately increases.

Complementary goods are goods, these are goods, the set of which constitutes a single use value. For example, a watch and a strap for them; tape recorder and cassette. An increase in price and a decrease in demand for one of the complementary goods simultaneously causes a decrease in demand for the other good.

Expectations.

They are usually associated with the orientation of people to increase prices and incomes in the future. So, for example, in conditions of unstable money circulation, inflationary expectations lead to a rush demand for goods and services. Expectations of lower incomes may cause consumers to limit their spending and make less demand for goods and services in a given period.

In addition to these factors, the state of demand in a particular country is determined by the level of economic, social, cultural and political development of society, the structure of the gross national product produced, the size of the national income and the nature of its distribution, the standard of living of the population, the policy of the state in a particular period of time and other factors. .

We depicted the feedback between the price of a product and the quantity demanded in the form of a two-dimensional graph, on which the quantity demanded is plotted along the horizontal axis and the price is plotted along the vertical axis.

10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 Q

The process depicted is to place five price-quantity options on the chart, as shown in the following table:

We have drawn a graph by drawing perpendiculars from the corresponding points on the two axes. Each point on the graph represents a specific price and the corresponding quantity of a product that a consumer will buy at that price. On the graph, the resulting demand curve slopes down and to the right, since the relationship between price and quantity demanded by it is inverse. In the downward direction of the demand curve, the law of demand is reflected - people buy more of a product at a low price than at a high one.

So far, we have considered the question of the position of a single consumer. But there are usually many consumers in the market. The transition from the scale of individual demand to the scale of market demand can be carried out by summing up the quantities demanded by each consumer at different possible prices. The following table shows the case where there are three buyers in the market.

|

Unit price, R, |

The value of individual demand |

|||

|

buyer Q 1 |

2nd buyer Q 2 |

3rd customer Q 3 |

Total value demand per week (market demand) Q total \u003d Q 1+ Q 2+ Q 3 |

|

The following figures show the summation process in a graphical representation, and only one price is used for this - 3 conventional units. units To derive a demand curve, we combine the three individual demand curves horizontally.

35Q1 39Q2 26Q3

G  )

P

)

P

Market Demand Curve - Sum of Individual Demand Curves

35 + 39 + 26 = 100Q

2. Perfect competition and its main features

In a market economy, all business entities act separately and act in relation to each other as competitors.

Under economic competition understand the competition of economic entities in the market for the preference of consumers in order to obtain the greatest profit (income). Competition is a necessary and important element of the market mechanism, but its very nature and forms are different in different markets and in different market situations.

In a market economy, competition is an important mechanism of economic relations between producers and consumers. So, if more goods are delivered to the market than buyers are able to purchase, then sellers will fight for the buyer, while lowering prices. If fewer goods are delivered to the market than the buyers are willing to purchase, then the latter will compete for the seller, thereby raising prices.

Competition, although it is associated with certain costs (increases socio-economic differentiation in society, causes the loss of economic resources from the ruin of the vanquished, etc.), at the same time provides a considerable economic effect, stimulating price reduction, improving quality and expanding the range of products , introduction of scientific and technological achievements, etc.

In modern economic science, there are four market models, and, accordingly, types of competition:

perfect (pure) competition

monopolistic competition,

oligopoly

pure monopoly.

The last three types of competition are combined into a common name - "imperfect competition". The degree of market competitiveness is determined by the ability of firms to influence it and, above all, prices. The smaller this influence, the more competitive the market is considered.

Character traits The main market models can be represented as follows:

|

Character traits |

Market Models |

|||

|

Pure competition |

monopoly competition |

Oligopoly |

monopoly |

|

|

Number of firms |

Very big |

Some |

||

|

Product type |

Standardization roved |

Differentiated |

Standardized and differentiated |

Unique; no close substitutes |

|

Price control |

Absent |

Some but in narrow confines |

Limited mutual dependence bridge; signifi- telny with tai- nom collusion |

Significant |

|

Availability of information |

Equal and own baud access |

Some difficulties |

Some restrictions |

Some restrictions |

|

Conditions for entering the industry |

Very light obstacles missing |

Relatively |

significant obstacles |

Blocked |

|

Non-price competition |

Absent |

Very typical especially when differentiation product |

companies with public organizations |

|

|

rural economy |

Production clothes, shoes |

Production cars |

public utilities |

|

Let's take a closer look at perfect competition and its main features.

Pure (perfect) competition characterized a large number competing sellers who offer a standard, homogeneous product to many buyers. The volume of production and supply by each individual producer is so insignificant that none of them can have a noticeable effect on the market price. The price of homogeneous products in such a market develops spontaneously under the influence of supply and demand. It is based on the social value of commodities, which is determined not by individual, but by socially necessary expenditures of labor for the production of a unit of output. At a given price, the consumer does not care which seller to buy the product from. In a competitive market, the products of firms B, C, D, D, etc. are considered by buyers as exact analogues of the product of company A. Due to the standardization of products, there is no basis for non-price competition, that is, competition based on differences in product quality, advertising or sales promotion.

Competitive market participants have equal access to information, i.e. all sellers have an idea about prices, production technology, and possible profits. In turn, buyers are aware of prices and their changes. In such a market, new firms are free to enter and existing firms are free to leave. There are no legislative, technological, financial or other serious obstacles for this. The limiter here is only the profit received. Each entrepreneur will produce goods up to the point where price and marginal cost do not equalize. Up to this point, he will exist in this industry, after it he leaves the industry, moving capital to the one that brings the highest profit. This in turn means that resources under conditions of pure competition are distributed efficiently.

It should be noted that perfect competition in its purest form is a rather rare phenomenon. However, the study of this market model is of great analytical and practical importance and its purpose is:

study demand from the point of view of a competitive seller,

understand how a competitive manufacturer adjusts to the market price in the short run,

explore the nature of long-term changes and adjustments in the industry,

to assess the effectiveness of competitive industries from the point of view of society as a whole.

Task number 1.

Suppose there are 10 million workers in Canada, each of whom can produce 2 cars or 30 tons of wheat per year.

What is the opportunity cost of producing 1 car in Canada?

What is the opportunity cost of producing 1 ton of wheat per year?

Draw the Canadian production possibilities frontier. If Canada consumes 10 million cars, how much wheat will it consume?

Limited economic resources and unlimited

human needs give rise to fundamental economic

problem - choice problem directions and methods of distribution

limited resources between different competing goals.

Obviously, the choice in favor of one of the directions implies

inevitable rejection of alternative industries. The resulting

losses (in physical or value terms) are called alter-

native costs, or opportunity cost

(opportunity cost - English) production of this product. Opportunity cost is the monetary gain from the most beneficial of all alternative uses of resources.

In this example, 10 million workers could produce 20 million cars a year, but if they produced 1 car instead, the opportunity cost would be 20 million cars - 1 car. = 19 999 999 cars, i.e. this is the number of cars that were not produced.

The situation is similar with the cost of lost opportunities for the production of 1 ton of wheat per year. 10 million workers multiplied by 30 tons of wheat = 300 million tons per year can be produced by workers, but if they produce 1 ton, then the opportunity cost will be 300 million tons - 1 ton =

299 999 999 tons of wheat.

Now let's draw the Canadian production possibilities frontier:

0![]() 100 200 300

100 200 300

On the Canadian production possibilities graph, the horizontal is the amount of wheat, and the vertical is the number of cars. The chart data is, of course, only an abstract model of Canada's actual manufacturing potential. But it is important for us to show that at any moment in time the country has limited capabilities and cannot break out of the production possibilities frontier.

The graph shows that if Canada consumes 10 million cars, then the amount of wheat consumed will be 250 million tons.

Task number 2.

Determine the average and marginal product of the firm if the following data are known:

When will the law of diminishing returns come into play in this case? Draw a graph of the firm's average and marginal products. What is the relationship between these curves?

marginal product - these are changes in the total (cumulative) product per 1 worker, with an increase or decrease in the number of employed workers.

For example, in our problem: when the number of workers increases from 4 to 5, then the total product per year increases from 120 to 130. Therefore, the marginal product of the 5th worker will be = 130 - 120 = 10. Similarly, we calculate the marginal product of the remaining workers.

Average product is the output per worker employed. The average product is equal to the ratio of the total output to the number of workers.

|

Number of workers |

Aggregate (general) product, TR |

Ultimate |

|

Law of diminishing returns states that, starting from a certain moment, the successive addition of units of a variable resource to an unchanged, fixed resource gives a decreasing marginal product per each subsequent unit of a variable resource.

For this example, the law of diminishing returns will begin to operate from the moment the number of employees increases to 3 people.

Graphically, the firm's average and marginal products would look like this:

Increasing Decreasing marginal Negative

Ultimate return Ultimate return

50 recoil

4 0

0

30 average product

20 limit

product

number of workers

The relationship between the curves of average and marginal product is as follows: where marginal product exceeds the average, the latter increases. Wherever marginal product is less than average product, average product declines. It follows that the curve of marginal product intersects the curve of average product just at the point at which the latter reaches its maximum.

List of used literature:

Dolan E.J., Lindsay D. Microeconomics. SPb., 1997

Zubko N.M. Economic theory - Mn .: "NTC API", 1998.

Demand and offer elements market mechanism

Law >> EconomicsDemand and sentence - elements market mechanism. Demand. Law demand. Demand- this is a form of expression of need, the amount ... will best satisfy him individual needs in general. Formed individual demand Buyers' intention to buy...

Kazakov A.P., Minaeva N.V. Economy. Fundamentals training course economic theory. - M .: LLC "GNOMPRESS", 1998.

The system and its structure. Demand and patterns of its change: a) law demand. Individual And market demand; b) change factors demand; c) price elasticity demand ...

Demand, supply and their interaction

The logic of behavior of the main market participants ¾ buyers and sellers ¾ is reflected by two market forces: demand And offer . The result of their interaction is a transaction ¾ agreement of the parties on the sale of goods and / or services in a certain quantity and for a certain price .

All market transactions are interconnected. If a certain commodity is sold to anyone at a certain price, then a similar commodity cannot, under the same conditions, cost more or less. One transaction affects another, the demand (or supply) that has appeared in one place affects general state market . In other words, competitive pricing accumulates in the price a huge amount of various information about the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of economic processes, forms the information-incentive basis of a market economy.

Supply and demand are, in a certain sense, a market substitute (or market equivalent) for the regulatory mechanism that was characteristic of the planned economy, when it was assumed that all the variety of economic information was known to the central planning authority. And if the planners only tried, on the basis of their own “comprehensive” awareness, to develop the most rational ways to achieve socio-economic goals and determine the directions of action for all persons involved in economic processes, then the mechanism of supply and demand really implements all these goals in a market economy.

Law of demand

The concept of demand

The demand of buyers for certain goods is formed under the influence of needs , i.e., the desire of a person to provide for himself better conditions life. Needs are highly individual; they are different for each person and are formed under the influence of a number of factors that determine the conditions of existence:

· himself (for example, the need or lack of need for warm clothes is determined by the climate of the country, the degree of hardening of a person, his tastes);

his family and close circle (for example, the need for educating children and the strength of its manifestation depend on the level of development of society and on the place that this individual occupies in society);

The social, national, religious and other community to which a person belongs (say, the need for national defense depends on the international position of the state of which the person is a citizen).

At the same time, out of a huge range of human needs, economic science is primarily interested in those that are supported by appropriate financial opportunities, in other words, it is interested in “effective demand”. Thus, demand ¾ is the desire and ability of buyers to make transactions to purchase goods available on the market.. And the quantity demanded is the amount of goods that buyers are willing and able to purchase at a given price within a certain time.

Law of demand

It is well known that, generally, at a low price, goods can be sold more quickly and in greater quantities than at a higher price. At the same time, increased, rush demand leads to price gouging, and sluggish and reduced ¾ to their reduction. This inverse relationship between the market price of a commodity and the quantity that can be bought or sold at that price is called the law of demand.

According to According to the law of demand, consumers, ceteris paribus, will buy the greater the quantity of goods, the lower their market price. Another formulation of this law is also possible: The law of demand consists in an inverse relationship between the price level and the quantity of goods purchased.

Immediate premises of the law of demand

The law of demand is one of the fundamental laws of a market economy. The deepest reasons for its existence are rooted in the very nature of value and prices. These will be discussed later in the analysis of theories of value. For now, we confine ourselves to listing the immediate prerequisites for its occurrence:

1) a decrease in price leads to an increase in the number of buyers to whom this product becomes available;

2) the same consumer can afford to buy more of the cheaper product. In the economic literature, this phenomenon is called income effect , since a decrease in prices is tantamount to an increase in consumer income;

3) the cheaper product "draws off" part of the demand, which otherwise would be directed to the purchase of other goods. This phenomenon also has special name ¾ substitution effect .

Demand and price

The law of demand establishes an inverse relationship between the price and the volume of products that consumers want to buy. Thus, this law proclaims price as the main factor determining the size of demand. But economic practice convinces us of the opposite: market economy 1 Demand is largely determined by price. Not by chance, if you do not take into account extreme situations, it is the price that primarily interests the consumer who decides to buy the product. And all other characteristics are necessarily considered through the prism of prices (remember how we argue, for example, about such an important characteristic as quality: expensive car but worth the money.

The relationship between the price of a product and the demand for it can be represented in tabular, graphical and functional ways. Suppose we know how many kilograms of sausage can be sold in a neighboring supermarket in a week at various price levels. Then the relationship between at the price And demand can be presented in the form of a table.

The same dependence can be presented in the form of a graph in the coordinates of sausage prices (P ¾ independent variable) and the amount of sausage purchased (Q ¾ dependent variable 2) (Fig. 4.1.). To build a graph, we use the data of our hypothetical example (Table 4.1)

Table 4.1.A conditional example of the relationship between the size of demand for sausage and its price

Line D is called the demand curve. It shows how much (Q) of the product buyers are willing to buy:

a) at any given price level;

b) in a specific period of time;

c) with other factors unchanged.

In other words, movement along the demand curve (from one point to another) reflects a change in the amount of a good that consumers demand as a result of a change in the price of the good.

The functional relationship between the volume of demand (Q D) and the price can also be presented in analytical form, i.e., in the form of a formula

Rice. 4.1. Dependence of demand on price

However, in such general form it does not reflect the inverse relationship between demand and price, and practical application formula needs to be specified. For example, if the dependence is linear, it will take the form:

where a, b ¾ are numerical coefficients.

In our conditional example, it will look like this:

Q D \u003d 300 - 5P.

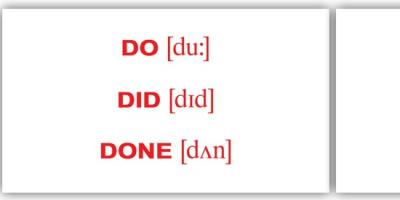

Individual and market demand

IN economic theory it is customary to distinguish between individual demand, as the demand of an individual buyer for a particular product, and market demand, i.e., the total demand of all buyers for each product price. If we denote by qij the individual demand for i-th product j-th buyer, then the market demand can be expressed as

where Q i ¾ market demand, n ¾ the number of buyers in the market.

The individual demand curve, having, like the market demand curve, a negative slope, that is, reflecting the inverse relationship between demand and price already described, is not smooth, but rather has a stepped form.

To induce a person, say, to buy two packs of butter instead of one, a small reduction in price from the usual level is not enough. That is, if instead of 10 rubles. (Moscow price at the beginning of 1999) it will cost 9 rubles. 80 kopecks, then 9 rubles. 60 kopecks, then 9 rubles. 40 kopecks, then all these changes, most likely, will not force one particular buyer to double the purchase volume. But at some point (for example, at a price of 8 rubles), he will react by increasing the purchased quantity of the product. There will be a jump in demand on the chart, a “step”. Since the “sensitivity threshold” of consumers is different, then, summing up, the step curves of individual demand will smooth each other out and eventually create a smooth curve of market demand.

Demand is the main factor determining what and how to produce. Distinguish between individual and market demand.

The consumer's individual demand function characterizes his reaction to a change in the price of a given good, assuming that his income and the prices of other goods remain unchanged.

INDIVIDUAL DEMAND - the demand of a particular consumer; is the amount of goods corresponding to each given price that a particular consumer would like to buy at market.

Rice. 12.1. Effect of price changes

On fig. 12.1 shows the consumer choice on which the individual stops, distributing a fixed income between two benefits when food prices change.

Initially, the price of food was 25 rubles, the price of clothing was 50 rubles, and the income was 500 rubles. The utility-maximizing consumer choice is at point B (Figure 12.1a). In this case, the consumer buys 12 units of food and 4 units of clothing, which makes it possible to provide a level of utility determined by an indifference curve with a utility value equal to U 2 .

On fig. 12.16 interrelation between the price for the foodstuffs and their required volume is represented. The abscissa shows the volume of consumed good, as in Fig. 12.1a, but food prices are now plotted on the y-axis. Point E in fig. 12.16 corresponds to point B in fig. 12.1a. At point E, the price of food is 25 rubles. and the consumer purchases 12 units.

Let us assume that the price of food has risen to 50 r. Since the budget line in Fig. 12.1a rotates clockwise, it becomes twice as steep. The higher food price increased the slope of the budget line, and the consumer in this case achieves maximum utility at point A, located on the indifference curve U 1 . At point A, the consumer chooses 4 units of food and 6 units of clothing.

On fig. 12.16 it is shown that the modified choice of consumption corresponds to point D, depicting that at a price of 50 rubles. 4 units of food are required.

Let us assume that the price of food falls to 12.5 rubles, which will cause the budget line to rotate counterclockwise, providing more high level utility corresponding to the indifference curve U 3 in Fig. 12.1a, and the consumer will choose point C with 20 food items and 5 clothing items. Point F in fig. 12.16 corresponds to a price of 12.5 rubles. and 20 units of food.

From fig. 12.1a it follows that with a decrease in food prices, clothing consumption can both increase and decrease. Consumption of food and clothing may increase as a fall in the price of food increases the purchasing power of the consumer.

The demand curve in fig. 12.16 depicts the amount of food that the consumer purchases as a function of the price of food. The demand curve has two peculiarities.

First. The level of utility achieved changes as one moves along the curve. The lower the price of a good, the higher the level of utility.

Second. At each point on the demand curve, the consumer maximizes utility under the condition that the marginal rate of substitution of food for clothing is equal to the ratio of food to clothing prices. As food prices fall, so does the price ratio and the marginal rate of substitution.

Change along the curve individual demand The marginal rate of substitution indicates the benefits delivered to consumers from goods.

MARKET DEMAND characterizes the total demand of all consumers at any given price of a given good.

The total market demand curve is formed as a result of horizontal addition of individual demand curves (Fig. 12.2).

The dependence of market demand on the market price is determined by summing the demand volumes of all consumers at a given price.

Graphical way the summation of the volumes of demand of all consumers is shown in fig. 12.2.

It must be borne in mind that hundreds and thousands of consumers operate in the market, and the volume of demand for each of them can be represented as a point. In this case, the demand point A is shown on the DD curve (Fig. 12.2c).

Each consumer has its own demand curve, that is, it differs from the demand curves of other consumers, because people are not the same. Some have a high income, while others have a low income. Some want coffee, others want tea. To obtain the overall market curve, it is necessary to calculate the total amount of consumption of all consumers at each given price level.

Rice. 12.2. Building a market curve based on individual demand curves

The market demand curve generally slopes less than individual demand curves, which means that when the price of a good falls, the quantity demanded in the market increases more than the quantity demanded by the individual consumer.

Market demand can be calculated not only graphically, but also through tables and analytical methods.

The main drivers of market demand are: