Introduction

1. Thinkers Ancient China

Three Greatest Thinkers of Ancient China

2.1Lao Tzu

2 Confucius

Conclusion

Bibliography

Introduction

China - country ancient history, culture, philosophy.

Ancient China arose on the basis of Neolithic cultures that developed in the 5-3 millennia BC. in the middle reaches of the Yellow River. The Yellow River basin became the main formation area ancient civilization China, which developed for a long time in conditions of relative isolation. Only from the middle of the 1st millennium BC. e. The process of expanding the territory begins in a southern direction, first to the Yangtze basin area, and then further to the south.

At the end of our era, the state of Ancient China extended far beyond the Yellow River basin, although the northern border of the ethnic territory of the ancient Chinese remained almost unchanged.

Ancient Chinese class society and statehood formed somewhat later than the ancient civilizations of Ancient Western Asia, but nevertheless, after their emergence, they began to develop at a fairly rapid pace and high forms of economic, political and cultural life were created in Ancient China, which led to the formation of the original socio-political and cultural system.

Chinese philosophy is part of Eastern philosophy. Its influence on the cultures of China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam and Taiwan is equivalent to the influence of ancient Greek philosophy on Europe. Thus, the relevance of the topic lies in the fact that the thinkers of Ancient China left their mark on history, whose experience is currently being used.

The purpose of this work: to study the greatest thinkers of Ancient China and characterize the main provisions of their teachings.

. Thinkers of Ancient China

China's religions have never existed in the form of a rigidly centralized "church." The traditional religion of ancient China was a mixture of local beliefs and ceremonies, united into a single whole by the universal theoretical constructs of pundits.

However, the most popular among both the educated and the peasantry were the three great schools of thought, often called the three religions of China: Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism. All these teachings are more philosophical than religious, in contrast to ancient Indian philosophy, which has always been closely connected with the religious tradition.

Ancient Chinese philosophy arose approximately in the middle of the 1st millennium BC. The ideas that formed the basis of philosophy were formed in monuments of the ancient Chinese literary tradition such as “Shu Jing” (“Book of Documentary Writings”), “Shi Jing” (“Book of Poems”), “I Ching” (“Book of Changes”).

Ancient Chinese philosophy is characterized by features that are not characteristic of other Eastern philosophical traditions. It must be said that the ancient Chinese had no idea about a transcendental God, about the creation of the world by God out of nothing, and had no idea about the dualism of the ideal and material principles of the world. In Ancient China, the traditional ideas for the West, India, and the Middle East did not develop about the soul as a kind of immaterial substance that separates from the body after death. Although ideas about the spirits of ancestors existed.

The Chinese worldview is based on ideas about qi. Qi is understood as a kind of vital energy that permeates absolutely everything in the world. Everything in the world is a transformation of Qi.

Qi is a kind of quasi-material substance that cannot be defined only as material or spiritual.

Matter and spirit are inseparable, they are consubstantial and interreducible, that is, spirit and matter are in a state of constant mutual transition.

At the core of existence is the Primordial Qi (Limitless, Chaos, Unity), which is polarized into two parts - yang (positive) and yin (negative). Yang and Yin are mutually transitive. Their transition constitutes the great Tao-path.

The negative potentially contains the positive and vice versa. Thus, Yang power reaches its limit and turns into Yin and vice versa. This position is called the Great Limit and is depicted graphically as a “Monad”.

Considering everything that exists as a unity of opposite principles, Chinese thinkers explained the endless process of movement by their dialectical interaction. Filling the Universe, generating and preserving life, these primary substances or forces determine the essence of the Five Elements: Metal, Wood, Water, Fire and Soil.

Actually, these ideas underlie ancient Chinese philosophy and are supported by all Chinese thinkers, with some differences in interpretation.

Differences between Chinese philosophy and Western philosophy: integral (holic) perception instead of analytical and cyclical processes instead of their static, linear nature. The three greatest thinkers of Ancient China that we will focus on in the next chapter are:

Lao Tzu- covered with an aura of mystery;

Confucius- revered by everyone;

Mo Tzu- now little known, who, however, more than four centuries before the birth of Christ formulated the concept of universal love.

Getting to know the views of these thinkers is made easier by the fact that there are three texts directly related to their names.

2. Three Greatest Thinkers of Ancient China

.1 Lao Tzu

Lao Tzu - a nickname meaning "old teacher" - is the great sage of Ancient China who laid the foundations of Taoism - a direction of Chinese thought that has survived to this day. Approximately, the life of Lao Tzu dates back to the 7th-6th centuries BC. He is considered the author of the main treatise of Taoism, “Tao Te Ching,” which became the most popular test of ancient Chinese philosophy in the West.

Little is known about the life of this sage and the authenticity of the available information is often criticized by scientists. But it is known that he was the custodian of the imperial archive of the Zhou court - the greatest book depository of Ancient China. Therefore, Lao Tzu had free access to various ancient and contemporary texts, which allowed him to develop his own teaching.

The fame of this sage spread throughout the Celestial Empire, so when he decided to leave the kingdom of Zhou, he was stopped at an outpost and asked to leave his teachings in written form for his kingdom. Lao Tzu compiled the treatise “Tao Te Ching”, which translates as “The Canon of the Path and Grace”. The entire treatise talks about the category of Tao.

Tao means “The Way” in Chinese. According to Lao Tzu, Tao lies at the basis of the world and the world realizes Tao. Everything in the world is Tao. Tao is inexpressible, it can be comprehended, but not verbally. Lao Tzu wrote: “The Tao that can be expressed in words is not the permanent Tao.” The doctrine of Tao is closely related to the doctrine of the mutual transition of opposites.

Lao Tzu, who lived earlier than two other great Chinese thinkers (VI-V centuries BC), is not easy to understand not only because his basic concept of “Tao” is very ambiguous: it is both “the main thing over many things” and “mother earth and sky”, “the fundamental principle of the world”, and “root”, and “path”; but also because in comprehending this concept we do not have the opportunity (as, for example, in ancient Indian and other cultures) to rely on any mythological images that would facilitate assimilation. Tao is as vague in Lao Tzu as the concept of Heaven is in all Chinese culture.

Tao is the source of all things and the basis for the functioning of existence. One of the definitions of Tao is “root.” The root is underground, it is not visible, but it exists before the plant that emerges from it. The invisible Tao, from which the whole world is produced, is also primary.

Tao is also understood as a natural law of the development of nature. The main meaning of the hieroglyph “dao” is “the road along which people walk.” Tao is the path that people follow in this life, and not just something outside it. A person who does not know the path is doomed to error, he is lost.

Tao can also be interpreted as unity with nature through subordination to the same laws. “The path of a noble man begins among men and women, but his deep principles exist in nature." Since this universal law exists, there is no need for any moral law - either in the natural law of karma or in the artificial law of human society.

Ecologists point to the closeness of Taoism to the emerging new understanding of nature. Lao Tzu advises adapting to natural cycles, indicates self-propulsion in nature and the importance of balance, and perhaps the concept of “tao” is a prototype of modern ideas about cosmic information belts.

Tao is sought within oneself. “He who knows himself can find out [the essence of things], and he who knows people is able to do things.” To know the Tao, you need to free yourself from your own passions. He who knows the Tao achieves “natural balance” because he brings all opposites into harmony and achieves self-satisfaction.

Tao desires nothing and strives for nothing. People should do the same. Everything natural happens as if by itself, without any special effort of the individual. The natural course is contrasted with the artificial activity of a person pursuing his own selfish, selfish goals. Such activity is reprehensible, therefore the main principle of Lao Tzu is not action (wu wei) - “non-interference”, “non-resistance”. Wuwei is not passivity, but rather non-resistance to the natural course of events and activity in accordance with it. This is a principle by following which a person maintains his own integrity, while at the same time gaining unity with existence. This is the path to realizing one’s own Tao, which cannot be different from the universal Tao. Finding one’s own Tao is the goal of every Taoist and should be the goal of every person, but this is difficult to achieve and requires a lot of effort, although at the same time it takes away from any strain of strength.

To better understand the teachings of Lao Tzu, it is necessary to immerse yourself in reading his treatise and try to understand it at an internal intuitive level, and not at the level of logical-discursive thinking, which our Western mind always turns to.

.2 Confucius

Taoism thinker Confucius philosophical

A younger contemporary of Lao Tzu, Confucius or Kong Tzu “Master Kun” (c. 551 - c. 479 BC) pays the traditional Chinese cultural tribute to Heaven as the creator of all things and calls for unquestioningly following fate, but pays the main attention to conscious design social connections necessary for the normal functioning of society. Confucius is the founder of the doctrine known as Confucianism.

“Teacher Kun” was born into a poor family, was left an orphan early and experienced poverty, although, according to legend, his family was aristocratic. The men of this family were either officials or military men. His father was already at an advanced age (70 years old) when he married a young girl (16 years old), so it is not surprising that when Confucius, or Qiu as he was called in the family, was 3 years old, his father passed away.

From a young age, Qiu was distinguished by his prudence and desire to learn. When he was seven years old, his mother sent him to a public school, where even then he amazed the teachers with his intelligence and wisdom. After training, Qiu entered the civil service. At first he was a sales officer overseeing the freshness of market products. His next job was as an inspector of arable fields, forests and herds. At this time, the future teacher Kun is still engaged in science and improves his ability to read and interpret ancient tests. Also at the age of 19, Qiu marries a girl from a noble family. He has a son and a daughter, but family life did not bring happiness to Confucius. The service began to bring Confucius popularity among officials and they began to talk about him as a very capable young man and it seemed that a new promotion was waiting for him, but his mother suddenly died. Confucius, faithfully fulfilling traditions, was forced to leave his service and observe three years of mourning.

Afterwards he returns to the work of a servant, but he already has students who have learned about the wisdom and knowledge of the great traditions of Confucius. At the age of 44, he took the high post of governor of the city of Zhongdu. The number of students grew. He traveled a lot and everywhere he found people willing to share his wisdom. After long travels, Confucius returns to his homeland, and last years He spends his life at home surrounded by numerous students.

Confucius's main work, Lun Yu (Conversations and Sayings), was recorded by his students and enjoyed such popularity throughout the subsequent history of China that it was even forced to be memorized in schools. It begins with a phrase that almost word for word coincides with one that is well known to us: “Learn and repeat what you have learned from time to time.”

The activity of Confucius falls on a difficult period for Chinese society of transition from one formation - slave-owning, to another - feudal, and at this time it was especially important to prevent the collapse of social foundations. Confucius and Lao Tzu took different paths to this goal.

The primacy of morality, preached by Confucius, was determined by the desire of the Chinese spirit for stability, tranquility and peace. The teachings of Confucius are devoted to how to make the state happy through the growth of morality, first of all, of the upper strata of society, and then of the lower ones. “If you lead the people through laws and maintain order through punishments, the people will strive to evade punishment and will not feel shame. If you lead the people through virtue and maintain order through rituals, the people will know shame and they will correct themselves.” The moral model for Confucius is a noble husband: devoted, sincere, faithful, fair. The opposite of a noble husband is a low man.

The desire for realism led Confucius to follow the rule “ golden mean"- avoiding extremes in activity and behavior. "A principle such as the 'golden mean' is the highest principle." The concept of the middle is closely related to the concept of harmony. A noble husband “... strictly adheres to the middle and does not lean in either direction. This is where true strength lies! When order reigns in the state, he does not abandon the behavior that he had before... When there is no order in the state, he does not change his principles until his death.” Greek philosophers responded the same way. But the noble man is not reckless. When order reigns in the state, his words contribute to prosperity; when there is no order in the state, its silence helps it preserve itself.

Of great importance both in the history of China and in the teachings of Confucius is the adherence to certain, once and for all established rules and ceremonies. “The use of ritual is valuable because it brings people to agreement. Ritual recognizes only those actions that are sanctified and verified by tradition. Reverence without ritual leads to fussiness; caution without ritual leads to timidity; courage without ritual leads to turmoil; directness without ritual leads to rudeness.” The purpose of the ritual is to achieve not only social harmony within, but also harmony with nature. “The ritual is based on the constancy of the movement of the sky, the order of phenomena on earth and the behavior of the people. Since heavenly and earthly phenomena occur regularly, then the people take them as a model, imitating the clarity of heavenly phenomena, and are consistent with the nature of earthly phenomena... But if this is abused, then everything will get confused and the people will lose their natural qualities. Therefore, a ritual was created to support these natural qualities.”

Ritual, in a picturesque expression, “is the beauty of duty.” What is a person's debt? The father must show parental feelings, and the son must show respect; the elder brother - kindness, and the younger - friendliness, the husband - justice, and the wife - obedience, the elders - mercy, the younger - obedience, the sovereign - philanthropy, and the subjects - devotion. These ten qualities are called human duty.

Confucius proclaimed a principle that runs like a red thread through the entire history of ethics: “Do not do to others what you do not wish for yourself.” He was not the first to formulate this moral maxim, which was later called the “golden rule of ethics.” It is found in many ancient cultures, and then among modern philosophers. But this saying expresses the essence of the basic concepts of Confucius - philanthropy, humanity.

We find in Confucius many other thoughts regarding the rules of community life. Don’t be sad that people don’t know you, but be sad that you don’t know people.” “Do not enter into the affairs of another when you are not in his place.” “I listen to people’s words and look at their actions.”

Understanding the importance of knowledge, Confucius warned against an exaggerated idea of one's own knowledge: “When you know something, consider that you know; Without knowing, consider that you don’t know - this is the correct attitude towards knowledge.” He emphasized the importance of combining learning with reflection: “Learning without thought is in vain, thought without learning is dangerous.”

The similarity between Lao Tzu and Confucius is that both of them, in accordance with the archetype of Chinese thought, sought permanence, but Lao Tzu found it not in action, but Confucius found it in permanence of activity - ritual. The call for limiting needs was also common.

The difference between them is what they considered more important. But Lao Tzu also wrote about philanthropy, and Confucius said: “If you know the right path in the morning, you can die in the evening.”

.3 Mo Tzu

Mo Tzu (Mo Di) - the founder of the teachings and school of the Mohists, identified wisdom and virtue, and with his preaching of love he was close to Christ.

The years of Mozi's life are approximately 479 - 381. BC. He was born in the kingdom of Lu and belonged to the "Xia", that is, wandering warriors or knights. "Xia" were often recruited not only from the impoverished houses of the nobility, but also from the lower strata of the population. Mo Tzu was initially an admirer of Confucianism, but then moved away from it and created the first oppositional teaching. The critical attitude towards Confucianism was due to dissatisfaction with the existing traditional and rather burdensome system of rules of behavior and ritual. Compliance with all the rules of the ritual often required not only internal, but also external efforts. The ritual took a lot of time and sometimes forced one to spend a lot of money on its exact observance. As a result, Mo Tzu comes to the conclusion that ritual and music are a luxury inaccessible to the lower strata or the impoverished nobility, and therefore require abolition.

Mo Tzu and his followers organized a strictly disciplined organization that was even capable of conducting military operations. Mo Tzu was “perfectly wise” in the eyes of his disciples.

Mo Di preached the principle of universal love and the principle of mutual benefit. Mo Tzu formulated the principle of universal love in a clear form, contrasting love that “knows no differences but the degree of kinship” with separate, egoistic love, that each person should love another as the closest, for example, like his father or mother. Note that love (in the understanding of Mo Tzu) concerns relationships between people, and not towards God, as in Christianity.

The principle of mutual benefit suggested that everyone should share their sorrows and joys, as well as poverty and wealth with everyone, then all people would be equal. These principles were implemented within the organization created by Mo Di.

Lao Tzu and Confucius emphasized the importance of the will of Heaven as a higher power. According to Mo Tzu, the events of our life do not depend on the zero of Heaven, but on the efforts made by man. However, Heaven has thoughts and desires. “To follow the thoughts of Heaven means to follow universal mutual love, mutual benefit of people, and this will certainly be rewarded. Speaking against the thoughts of Heaven sows mutual hatred, encourages them to do harm to each other, and this will certainly entail punishment.” The authors of “The History of Chinese Philosophy” correctly write that Mo Tzu used the authority of Heaven as an ideological weapon to justify the truth of his views. Marx also subsequently used the idea of objective laws of social development.

Like all the great utopians, Mozi created his own concept of an ideal state and even an idea of three successive phases of social development: from the era of “disorder and unrest” through the era of “great prosperity” to a society of “great unity.” But not all people want a transition from disorder and unrest to prosperity and unity.

Mozi's views were very popular in IV-III centuries BC, but then the realism of Confucius still won in the practical soul of the Chinese. After the death of Mo Di, at the end of the 4th century BC. The Mo Di school undergoes a disintegration into two or three organizations. In the second half of the 3rd century BC. There was a practical and theoretical collapse of the organization and teachings of Mo Di, after which it was no longer able to recover, and in the future this teaching existed only as the spiritual heritage of Ancient China.

The teachings of Confucius are also aimed at an ideal, but the ideal of moral self-improvement. Mo Tzu was a social utopian and wanted the forced introduction of universal equality. Confucius took his place between Lao Tzu, with his actions, and Mo Tzu, with his violence; and his concept turned out to be the “golden mean” between passivity and extremism.

Conclusion

The most prominent philosophers of Ancient China, who largely determined its problems and development for centuries to come, are Lao Tzu (second half of the 6th - first half of the 5th century BC) and Confucius (Kung Fu-tzu, 551-479 BC). BC), as well as other thinkers, and primarily the philosophical heritage of Mo Tzu. These teachings give a fairly objective idea of the philosophical quests of ancient Chinese thinkers.

Lao Tzu is an ancient Chinese philosopher of the 6th-4th centuries BC, one of the founders of the teachings of Taoism, the author of the treatise “Tao Te Ching” (“Canon of the Way and Grace”). The central idea of Lao Tzu's philosophy was the idea of two principles - Tao and De. The word "Tao" literally means "way"; in this philosophical system it received a much broader metaphysical content. “Tao” means both the essence of things and the total existence of the universe. The very concept of “Tao” can also be interpreted materialistically: Tao is nature, the objective world.

Confucius is an ancient thinker and philosopher of China. His teachings had a profound influence on life in China and East Asia, becoming the basis of the philosophical system known as Confucianism. Although Confucianism is often called a religion, it does not have the institution of a church and is not concerned with theological issues. Confucian ethics is not religious. The teachings of Confucius concerned mainly social and ethical problems. The ideal of Confucianism is the creation of a harmonious society according to the ancient model, in which every individual has his own function. A harmonious society is built on the idea of devotion, aimed at preserving the harmony of this society itself. Confucius formulated Golden Rule ethics: “Do not do to a person what you do not wish for yourself.”

Mo Tzu is an ancient Chinese philosopher who developed the doctrine of universal love. The religious form of this teaching - Moism - for several centuries competed in popularity with Confucianism.

So, we can rightfully say that Laozi, Confucius and Mozi, with their philosophical creativity, laid a solid foundation for the development of Chinese philosophy for many centuries to come.

Bibliography

1.Gorelov A.A. Fundamentals of philosophy: textbook. allowance. - M.: Academy, 2008. - 256 p.

2.History of Chinese philosophy / Ed. M.L. Titarenko. - M.: Progress, 1989.- 552 p.

3.Lukyanov A.E. Lao Tzu and Confucius: Philosophy of Tao. - M.: Eastern literature, 2001. - 384 p.

.Rykov S. Yu. The doctrine of knowledge among the late Mohists // Society and state in China: XXXIX scientific conference / Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences. - M. - 2009. - P.237-255.

.Shevchuk D.A. Philosophy: lecture notes. - M.: Eksmo, 2008. - 344 p.

Tutoring

Need help studying a topic?

Our specialists will advise or provide tutoring services on topics that interest you.

Submit your application indicating the topic right now to find out about the possibility of obtaining a consultation.

Philosophy of ancient China: Lao Tzu's Book of Changes, the works of the thinkers Lao Tzu and Confucius - without these three things, the philosophy of ancient China would have resembled a building without a foundation - so great is their contribution to one of the most profound philosophical systems in the world.

Philosophy of ancient China: Lao Tzu's Book of Changes, the works of the thinkers Lao Tzu and Confucius - without these three things, the philosophy of ancient China would have resembled a building without a foundation - so great is their contribution to one of the most profound philosophical systems in the world.

The I Ching, that is, the Book of Changes, is one of the earliest monuments of the philosophy of Ancient China. The title of this book has a deep meaning, which lies in the principles of variability of nature and human life as a result of a natural change in the energies of Yin and Yang in the Universe. The Sun and Moon and other celestial bodies in the process of their rotation create all the diversity of the constantly changing celestial world. Hence the name of the first work of philosophy of Ancient China - “The Book of Changes”.

In the history of ancient Chinese philosophical thought, the “Book of Changes” occupies a special place. For centuries, almost every ancient Chinese thinker tried to comment on and interpret the content of the Book of Changes. This commentary and research activity, which lasted for centuries, laid the foundations of the philosophy of Ancient China and became the source of its subsequent development.

The most prominent representatives of the philosophy of Ancient China, who largely determined its problems and studied issues for two millennia to come, were Lao Tzu and Confucius. They lived during the 5th–6th centuries. BC e. Although Ancient China also remembers other famous thinkers, the legacy of these two people is considered the foundation of the philosophical quest of the Celestial Empire.

Lao Tzu - "The Wise Old Man"

The ideas of Lao Tzu (real name - Li Er) are set out in the book “Tao Te Ching”, in our opinion - “The Canon of Tao and Virtue”. Lao Tzu left this work, consisting of exactly 5 thousand hieroglyphs, to a guard on the Chinese border when he went to the West at the end of his life. The significance of the Tao Te Ching for the philosophy of ancient China can hardly be overestimated.

The central concept that is discussed in the teachings of Lao Tzu is "Tao". The main meaning of the character “dao” in Chinese is “path”, “road”, but it can also be translated as “root cause”, “principle”.

“Tao” for Lao Tzu means the natural path of all things, the universal law of development and change in the world. “Tao” is the immaterial spiritual basis of all phenomena and things in nature, including humans.

These are the words with which Lao Tzu begins his Canon on Tao and Virtue: “You cannot know Tao only by talking about It. And it is impossible to call by a human name that beginning of heaven and earth, which is the mother of everything that exists. Only one freed from worldly passions is able to see Him. And the one who preserves these passions can only see His creations.”

Lao Tzu then explains the origin of the concept “Tao” he uses: “There is such a thing formed before the appearance of Heaven and Earth. It is independent and unshakable, changes cyclically and is not subject to death. She is the mother of everything that exists in the Celestial Empire. I don't know her name. I’ll call it Tao.”

Philosophy of ancient China: the hieroglyph “Dao” (ancient style) consists of two parts. The left side means “to go forward”, and the right side means “head”, “prime”. That is, the hieroglyph “Tao” can be interpreted as “to walk along the main road.” Lao Tzu also says: “Tao is immaterial. It is so foggy and uncertain! But in this fog and uncertainty there are images. It is so foggy and uncertain, but this fog and uncertainty hides things within itself. It is so deep and dark, but its depth and darkness conceals the smallest particles. These smallest particles are characterized by the highest reliability and reality."

Speaking about the style of government, the ancient Chinese thinker considers the best ruler to be the one about whom the people only know that this ruler exists. A little worse is the ruler whom people love and exalt. Even worse is a ruler who inspires fear in the people, and the worst are those whom people despise.

Great importance in the philosophy of Lao Tzu is given to the idea of renouncing “worldly” desires and passions. Lao Tzu spoke about this in the Tao Te Ching using his own example: “All people indulge in idleness, and society is filled with chaos. I am the only one who is calm and does not expose myself to everyone. I look like a child who was not born into this idle world at all. All people are overwhelmed by worldly desires. And I alone gave up everything that was valuable to them. I’m indifferent to all this.”

Lao Tzu also cites the ideal of the perfectly wise man, emphasizing the achievement of "non-action" and modesty. “A wise person gives preference to non-action and remains at peace. Everything around him happens as if by itself. He has no attachment to anything in the world. He does not take credit for what he has done. Being the creator of something, he is not proud of what he created. And since he does not extol himself or boast, and does not strive for special respect for his person, he becomes pleasant to everyone.”

In his teachings, which had a great influence on the philosophy of ancient China, Lao Tzu encourages people to strive for Tao, talking about a certain blissful state that he himself achieved: “All Perfect people flock to the Great Tao. And you follow this Path! … I, being in inaction, wander in the boundless Tao. This is beyond words! Tao is the subtlest and most blissful."

Confucius: the immortal teacher of the Celestial Empire

The subsequent development of the philosophy of ancient China is associated with Confucius, the most popular Chinese thinker, whose teachings today have millions of admirers both in China and abroad.

The views of Confucius are set out in the book “Conversations and Judgments” (“Lun Yu”), which was compiled and published by his students based on the systematization of his teachings and sayings. Confucius created an original ethical and political teaching that guided the emperors of China as an official doctrine throughout almost the entire subsequent history of the Celestial Empire, until the communists gained power.

The basic concepts of Confucianism that form the foundation of this teaching are “ren” (humanity, philanthropy) and “li” (respect, ceremony). The basic principle of “ren” is don’t do to others what you wouldn’t want for yourself. “Li” covers a wide range of rules that essentially regulate all spheres of social life - from family to state relations.

Moral principles, social relations and problems of government are the main themes in the philosophy of Confucius.

In relation to knowledge and awareness of the surrounding world, Confucius mainly echoes the ideas of his predecessors, in particular Lao Tzu, even inferior to him in some ways. An important component of nature for Confucius is fate. The teachings of Confucius speak about fate: “Everything is initially predetermined by fate, and here nothing can be added or subtracted. Wealth and poverty, reward and punishment, happiness and misfortune have their own root, which cannot be influenced by the power of human wisdom.”

Analyzing the possibilities of knowledge and the nature of human knowledge, Confucius says that by nature people are similar to each other. Only the highest wisdom and extreme stupidity are unshakable. People begin to differ from each other due to their upbringing and as they acquire different habits.

Regarding the levels of knowledge, Confucius offers the following gradation: “The highest knowledge is the knowledge that a person has at birth. Below is the knowledge that is acquired in the process of studying. Even lower is the knowledge gained as a result of overcoming difficulties. The most insignificant is the one who does not want to learn an instructive lesson from difficulties.”

Philosophy of Ancient China: Confucius and Lao Tzu

Sima Qian, the famous ancient Chinese historian, describes in his notes how two philosophers once met each other.

He writes that when Confucius was in Xiu, he wanted to visit Lao Tzu to listen to his opinion regarding rituals (“li”).

Note, Lao Tzu said to Confucius, that those who taught the people have already died, and their bones have long since decayed, but their glory, nevertheless, has not yet faded. If circumstances favor the sage, he rides in chariots; and if not, he will begin to carry a load on his head, holding its edges with his hands.

China is known for its picturesque nature, majestic architecture and unique culture. But besides all this, the Celestial Empire is a country with a rich historical past, which includes the birth of philosophy. According to research, this science began its development in China. The treasury of eastern wisdom has been replenished over the years, centuries, centuries. And now, using quotes from the great sages of China, we don’t even suspect it. Moreover, we know nothing about their authors, although this is not only useful, but also interesting information.

The main book of ancient Chinese philosophers is "Book of Changes" . Its key role lies in the fact that most famous philosophers turned to it, tried to interpret it in their own way and based their philosophical reflections on it.

The most famous philosopher of Ancient China - (604 BC - 5th century BC e.)

It is he who is the creator of the treatise Tao Te Tzu. He is considered the founder of Taoism - the doctrine according to which Tao is the highest matter, which gives rise to everything that exists. It is a universally accepted fact that “Lao Tzu” is not the real name of the philosopher. His birth name Li Er, but in ancient times the names Li and Lao were similar. The name "Lao Tzu" translates to "Old Sage". There is a legend that the sage was born an old man, and his mother was pregnant for more than 80 years. Of course, modern researchers critically question this information. Lao Tzu's life was unremarkable: work at the emperor's court and philosophical reflections. But it was these reflections and works that made him the most famous philosopher and sage of Ancient China.

2.Confucius

3.Mencius

The next philosopher, about whom many who were interested in the culture of China have also heard, is Mencius. Philosopher whose teachings became the basis for Neo-Confucianism. The sage argued that a person is born initially good, and under the influence of his environment becomes what he is in the end. I published my thoughts in the book Mengzi. The philosopher also believed that any type of activity should be distributed according to a person’s abilities. For example, high ranks should be held by those who are intellectually gifted, and people capable only of physical activities should be subordinate to them. From a logical point of view, the theory is quite reasonable.

4. Gongsun Long

Have you ever heard of the School of Names? An analogue of such a school in Greece was the School of Sophists. The representative of the School of Names of China was a philosopher Gongsun Long. It is he who owns the quote “a white horse is not a horse.” Sounds absurd, doesn't it? Thanks to such statements, Gongsun deservedly received the nickname “master of paradoxes.” His statements are not clear to everyone, even if there is an interpretation. Perhaps for this you need to retire somewhere in the valley, with a cup of Chinese tea, and think about why a white horse is not really white.

5. Zou Yan

But the philosopher who decided to discuss the horse - Zou Yan- argued that the white horse is, in fact, white. This sage was a representative of the Yin Yang school. However, he was not only engaged in philosophy. His works in the field of geography and history have been preserved, which are confirmed even now. In other words, the definitions and patterns of Zou Yan, which were created thousands of years ago, are confirmed by modern scientists. Just imagine how intellectually developed this person was to describe the world around him so accurately!

6. Xunzi

An atheist sage can be considered Xunzi. The philosopher held high ranks more than once, but, unfortunately, did not last long in any of them. I had to part with one position because of slander, and I had to resign from another. Deciding that he could not build a successful career, Xunzi plunged headlong into thought and the creation of the treatise “Xugenzi” - the first philosophical work in which the thoughts of the sage were not only presented, but also systematized. Thanks to this, his quotes have come to us in the exact wording of their creator. The Chinese philosopher believed that a person’s Spirit appears only when he has fulfilled his true destiny. And all processes in the world are subject to the laws of Nature.

7. Han Fei

Taking his place among philosophers with rather strange statements Han Fei. The sage was born in the royal house and studied under Xun Tzu. But from birth he had speech defects, which undoubtedly influenced the attitude of others towards him. Perhaps this is why his thoughts differ significantly from the thoughts of his predecessors. For example, according to his treatise, mental and moral data do not in any way affect the qualities of the ruler as such, and subjects are obliged to obey any of his orders. For him, the ideal form of government was despotism. Although given his noble origins, this is not surprising. It seems that Han Fei, in his thoughts, imagined himself in the place of a ruler and sovereign.

8. Dong Zhongshu

A significant figure in the history of the development of Confucianism was Dong Zhongshu. This man not only thought, but also acted. It was thanks to this philosopher that Confucianism was presented as the main teaching of the Han Dynasty. It was according to his dogmas that life in the state developed, rulers were elected and decisions were made. According to his worldview, the ruler was sent to people from Heaven and all his further actions should be for the benefit of the people and to maintain harmony. But Heaven in its own way controls this process and if something goes wrong, it sends various natural disasters (flood, drought, etc.) to the state. Dong Zhongshu outlined all his ideas in the work “The Abundant Dew of the Chronicle of Chunqiu.”

9. Wang Chong

Not only was Zou Yan a philosopher and scientist, but also Wang Chong, who worked both in the fields of philosophy and in the fields of medicine and astronomy. He owns detailed description natural water cycle. And in philosophical ideas, the sage adhered to Taoism and interpreted the “Book of Changes.” The philosopher was repeatedly offered the position of court scientist, but having a freedom-loving and fairly independent character, Wang Chong refused each time, explaining this by poor health.

The philosophy of Ancient China dates back to the beginning of the 1st millennium BC. The formation of philosophical ideas in China took place in difficult social conditions. Already in the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. e. In the state of Shang-Yin (XVII-XII centuries BC), a slave-owning economic system emerged, and the emergence of the economy of Ancient China began.

The labor of slaves, into whom captured prisoners were converted, was used in cattle breeding and agriculture. In the 12th century BC. e. As a result of the war, the state of Shan-Yin was defeated by the Zhou tribe, which founded its own dynasty that lasted until the 3rd century. BC e.

In the era of Shang-Yin and in the initial period of the existence of the Jou dynasty, the dominant religious-mythological worldview was dominant. One of the distinctive features of Chinese myths is the zoomorphic nature of the gods and spirits acting in them.

The supreme deity was Shang Di - the first ancestor and patron of the Chinese state. Both gods and spirits obeyed him. Often the personified power of Heaven appeared in the image of Shan-di. According to the ideas of the ancient Chinese, the impersonal but all-seeing Heaven controlled the entire course of events in the Universe, and its high priest and only representative on earth was the emperor, who bore the title of Son of Heaven.

The “first” feature of Chinese philosophy (or rather mythology) was the cult of ancestors, which was built on the recognition of the influence of the spirits of the dead on the life and fate of descendants. The responsibility of the ancestors who became spirits was to constantly care for their descendants living on earth.

The “second” feature of ancient Chinese philosophy is the idea of the world as an interaction of opposite principles: female yin and male yang. In ancient times, when there was neither heaven nor earth, the Universe was a dark, formless chaos. Two spirits were born in him - yin and yang, who began to organize the world. The yang spirit began to rule the sky, and the yin spirit began to rule the earth. In the myths about the origin of the Universe there are very vague, timid beginnings of natural philosophy.

To understand Chinese philosophy, it is necessary to take into account that China is a world of right-hemisphere culture, which is expressed in culture of ancient China

The right hemisphere contains the world of visual images, musical melodies, and the centers of hypnosis and religious experiences are localized. In left-hemisphere cultures, the speech center and the center of logical thinking are powerfully developed. In right-hemisphere cultures, they hear and perceive sounds differently; it is very difficult for representatives of these cultures to express sounds literally; they perceive the world in specific, individual images.

Chinese philosophical thinking

Holism – The world and each individual are viewed as a “single whole”, more important than its constituent parts. Chinese holistic thinking emphasizes such characteristics of a phenomenon as “structure - function” rather than “substance - element”. The idea of the harmonious unity of man and the world is central to this thinking. Man and nature are considered not as subject and object opposing each other, but as a “holistic structure” in which body and spirit, somatic and mental are in harmonious unity.

Intuitiveness – in Chinese traditional philosophical thinking, methods of cognition similar to intuition are of great importance. The basis of this is holism. The “One” cannot be analyzed through concepts and reflected through language. To understand the “single integrity” one must rely only on intuitive insight.

Symbolism– traditional Chinese philosophical thinking used images (xingxiang) as a tool of thinking.

Tiyan - knowledge of the principles of the macrocosm was carried out through a complex cognitive act , including cognition, emotional experience and volitional impulses. Cognition was combined with aesthetic sensation and the will to implement moral norms in practice. The leading role in this complex was played by moral consciousness.

Philosophy – schools of ancient China

The beginning of a violent ideological struggle between various philosophical and ethical schools of ancient China caused deep political upheavals in the 7th-3rd centuries. BC e.- the collapse of the ancient unified state and the strengthening of individual kingdoms, intense struggle between large kingdoms.

The Zhanguo period in the history of Ancient China is often called the “golden age of Chinese philosophy.” It was during this period that concepts and categories emerged, which would then become traditional for all subsequent Chinese philosophy, right up to modern times.

At that time, there were 6 (six) main philosophical schools:

- Taoism: The Universe is the source of harmony, therefore everything in the world, from plants to humans, is beautiful in its natural state. The best ruler is the one who leaves people alone. Thinkers: Lao Tzu, Le Tzu, Zhuang Tzu, Yang Zhu; Wen Tzu, Yin Xi. Representatives of later Taoism: Ge Hong, Wang Xuanlan, Li Quan, Zhang Boduan

- Confucianism: The ruler and his officials should govern the country according to the principles of justice, honesty and love. Ethical rules, social norms, and regulation of the governance of an oppressive centralized state were studied. Thinkers: Confucius, Tseng Tzu, Tzu Si, Yu Ruo, Tzu Gao, Mencius, Xun Tzu.

- Moism: the meaning of the doctrine was the ideas of universal love and prosperity, everyone should care about mutual benefit. Representatives of Mohism: Mo Tzu, Qin Huali, Meng Sheng, Tian Xiang Tzu, Fu Dun.

- school of lawyers: dealt with problems of social theory and government controlled. Representatives of the philosophical school: Ren Buhai, Li Kui, Wu Qi, Shang Yang, Han Feizi; They also include Shen Dao.

- school of names: the discrepancy between the names of the essence of things leads to chaos. Representatives of Shola names: Deng Xi, Hui Shi, Gongsun Long; Mao-kung.

- “Yin-Yang” school (natural philosophers). Representatives of this school: Tzu-wei, Zou Yan, Zhang Tsang.

Another fundamental concept of Taoism, closely related to the concept of qi and the yin-yang principle, is the concept five primary elements, which are ranked as follows in terms of importance: water, fire, wood, earth and metal. These primary elements are given great importance throughout traditional Chinese philosophy, science, astrology and medicine; references to them are often found in Chinese texts; Chinese folklore is unthinkable without them, and, to one degree or another, they influence the everyday affairs of the Chinese.

STUDYING THE FIVE PRIMARY ELEMENTS

Any person who tries to seriously study the Taoist postulate of the five primary elements inevitably encounters an unusual mixture of mystery, superstition and logical constructions full of common sense. And the realization that this conglomeration of concepts has puzzled many of the best minds in the West, and even some thinkers in China itself, can hardly serve as sufficient consolation. The attitude of modern Chinese towards the five elements is similar to the attitude of Western Europeans towards the texts of the Old Testament: many unconditionally believe in what is written there, others tend to interpret them critically. And although the Chinese are ardent adherents of traditions, at the same time they are also characterized by pragmatism of thinking; It is unlikely that many of them perceive all the provisions of their traditional teaching without a certain amount of skepticism.

WHAT ARE THE FIVE PRIMARY ELEMENTS?

When defining the conceptual essence of the five primary elements, it is easier to identify what they are not than what is hidden under these categories. They are clearly not adequate to the four elements of the ancient Greeks - air, earth, fire and water, which were considered as the main components of the entire material Universe. They cannot in any way be linked with the hundred elements with which modern chemistry operates, such as oxygen, hydrogen, carbon, sulfur, iron, etc., and which are capable, in their various combinations, of forming a great variety of complex compounds. The five primary elements of the Chinese are intangible and poorly correlated with real entities. In other words, fire is not fire as such, water is not water, and so on.

These elements can be briefly and far from exhaustively represented as certain properties and influences. So, for example, those things that have the property of emitting heat, heating, be it feverish heat or sunlight, are considered to be related to or caused by the fire element. And with this approach, it is completely understandable why ancient Chinese philosophers describe the sun as a “fiery force,” but it is much more difficult to explain why they call the heart a “fiery organ” - although the warmth of the human body is maintained by the circulation of blood provided by the pulsation of the heart. Likewise, the kidneys and taste are associated with the water element, since both urine (produced by the kidneys) and sea water are equally salty in taste. Metals often have a shine, and therefore other objects, such as glass or a polished surface, are associated with the metal, or the shine of these objects is attributed to the influence of this element.

Ancient Chinese philosophers also used these five elements to explain phenomena that, although they did not fully understand them, existed in reality - the change of seasons, the movements of the planets, some functions of the body, as well as those concepts that in modern Western science are designated by letters from the Greek alphabet (for example, ψ) or special terms with the help of which the laws of nature are formulated in astronomy, chemistry, physics, biology, etc.

ESSENCE OF LANGUAGE

Although the origin of the five elements is shrouded in mystery, it is reasonable to assume that their development coincided with the development of language, having been an elementary idea thousands of years ago. There is evidence that yin-yang symbols were inscribed on turtle shells at a time when most people were very far from any education. The simple word “fire,” the meaning of which was clear to everyone without exception, was used to denote such concepts as heat, warmth, temperature, dryness, excitement, passion, energy, etc., the subtle semantic differences between which were simply not accessible to people’s understanding. In the same way, the word “water” concentrated the concepts: coldness, humidity, dampness, dew, current, etc.

ESSENCE OF PHILOSOPHY

The Huai Nan Zu, or Book of Huai Nan, written for one of the ancient princes and consisting of 21 volumes, explains how heaven and earth became yin and yang, how the four seasons arose from yin and yang, and how Yang gave birth to fire, the quintessence of which was embodied in the Sun.

Confucian sage Zhou Dunyi(1017-73) wrote about yin and yang:

Yin arises from inaction, while yang arises from action. When inaction reaches its climax, action is born, and when action reaches its maximum, inaction occurs again. This alternation of yin and yang gives rise to the five primary elements: water, fire, wood, metal and earth; and when they are in harmony with each other, the seasons smoothly follow each other.

In the treatise Shujing it is said that the purpose of water is to soak and fall; The purpose of fire is to warm and rise; The purpose of wood is to bend or be straight; the purpose of metal is to obey or change; The purpose of the earth is to influence sowing and harvest. Accordingly, the five primary elements also correlate with the five taste qualities recognized by the Chinese as salty, bitter, sour, dry and sweet.

Such explanations may seem far-fetched, but they also contain a certain logic. And it should be remembered that the ancient sages built their concepts without possessing the knowledge that is available to modern people.

RELATIONS

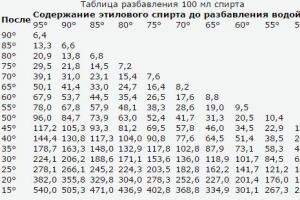

The table below shows how the five elements relate to different concepts. But if the parallel between fire, Mars, red color and bitterness is obvious, then some other associative chains are not so easy to explain logically.

| Water | Fire | Tree | Metal | Earth |

| Mercury | Mars | Jupiter | Venus | Saturn |

| black | red | green | white | yellow |

| salty | bitter | sour | dry | sweet |

| fear | pleasure | anger | anxiety | passion |

| rotten | caustic | rancid | disgusting | fragrant |

| cold | hot | windy | dry | wet |

| six | seven | eight | nine | five |

| pig | horse | rooster | dog | bull |

| kidneys | heart | liver | lungs | spleen |

ESSENCE OF MEDICINE

In Traditional Chinese Medicine, the five elements along with the five colors are used to represent the relationship between treatments and different organs, since vital organs are associated with certain emotions, herbal remedies have different tastes, and some disease conditions may be accompanied by a characteristic odor emanating from the human body. Such symbolic connections certainly had some benefit in times when doctors had limited scientific knowledge.

It is clear that the first healers in China were shamans, or sorcerers. Their treatment was reduced to a combination of sound therapy and various magical actions. And naturally, the sick, unless they were shamans themselves, had to believe that the elements had a beneficial effect.

ESSENCE OF ASTROLOGY

The five primary elements are given great importance in Chinese astrology, which is based on a 60-year cycle, which in turn is composed of two shorter cycles, the Ten Heavenly Stems and the Twelve Earthly Branches. Each of the Ten Heavenly Stems is designated by one of the five elements, both of yin and yang nature. And the Twelve Earthly Branches bear the names of twelve animals, each of which corresponds to one year of the so-called 12-year “animal” cycle. Moreover, each “animal” year also correlates with one of the five primary elements and can be of either a yin or yang nature. For example, 1966, which passed under the sign of the horse, fire and yang, symbolized the essence of a horse with a hot temperament. 1959 was the year of the pig, earth and yin and embodied the essence of the fair and impartial pig. Within a 60-year cycle, 60 different combinations are possible. Moreover, each combination is repeated only once in sixty years. So, 1930 was the year of the horse, metal and yang. 1990 passed under the same signs.

The characteristics of “animal” years are given in more detail in the section.