let `s talk about old Russian hut, or let’s take it even a little more broadly – a Russian house. Its appearance and internal organization- the result of the influence of many factors, from natural to social and cultural. Peasant society has always been extremely stable in its traditional way of life and ideas about the structure of the world. Even being dependent on the influence of the authorities (the church, Peter’s reforms), Russian folk culture continued its development, the crown of which must be recognized as the formation of a peasant estate, in particular a courtyard house with a residential old Russian hut.

The Russian house remains for many either some kind of allegory of Christian Rus', or a hut with three windows with carved platbands. For some reason, exhibits in museums of wooden architecture do not change this persistent opinion. Maybe because no one has clearly explained what it is, exactly. old Russian hut- literally?

Russian hut from the inside

A stranger explores the home first from the outside, then goes inside. One’s own is born within. Then, gradually expanding his world, he brings it to the size of ours. For him, the outside comes later, the inside comes first.

You and I, unfortunately, are strangers there.

So outside, old Russian hut tall, large, its windows are small, but located high, the walls represent a mighty log massif, not dissected by a base and cornices horizontally, or blades and columns vertically. The roof grows out of the wall like a gable; it is immediately clear that behind the “gable” there are no usual rafters. The ridge is a powerful log with a characteristic sculptural projection. The parts are few and large, there is no lining or lining. In some places, individual ends of logs of not entirely clear purpose may protrude from the walls. Friendly old Russian hut I wouldn't call her, rather, silent and secretive.

There is a porch on the side of the hut, sometimes high and pillared, sometimes low and indistinct. However, it is precisely this that is the first Shelter under which the newcomer enters. And since this is the first roof, it means that the second roof (canopy) and the third roof (the hut itself) only develop the idea of a porch - a covered paved elevation that projects the Earth and Heaven onto itself. The porch of the hut originates in the first sanctuary - a pedestal under the crown of the sacred tree and evolves all the way to the royal vestibule in the Assumption Cathedral. The porch of the house is the beginning of a new world, the zero of all its paths.

From the porch into the entryway there is a low wide door in a powerful oblique frame. Its internal contours are slightly rounded, which serves as the main obstacle to unwanted spirits and people with unclean thoughts. The roundness of the doorway is akin to the roundness of the Sun and Moon. There is no lock, a latch that opens both from the inside and from the outside - from wind and livestock.

The canopy, called a bridge in the North, develops the idea of a porch. Often they have no ceiling, just as there was no hut before - only the roof separates them from the sky, only it overshadows them.

The canopy is of heavenly origin. The bridge is earthly. Again, as in the porch, Heaven meets Earth, and they are connected by those who cut down old Russian hut with a vestibule, and those who live in it are a large family, now represented among the living link of the clan.

The porch is open on three sides, the entryway is closed on four, and there is little light in them from the glass windows (covered with boards).

The transition from the entryway to the hut is no less important than from the porch to the entryway. You can feel the atmosphere heating up...

The inner world of a Russian hut

We open the door, bending down, we enter. Above us low ceiling, although this is not a ceiling, but a floor - a flooring at the level of the stove bench - for sleeping. We are in a blanket shelter. And we can turn to the owner of the hut with good wishes.

Polatny kut - a porch inside a Russian hut. Any kind person can enter there without asking, without knocking on the door. The planks rest on the wall directly above the door with one edge, and on the canvas beam with the other. For this plated beam, the guest, at his will, is not allowed to go. Only the hostess can invite him to enter the next kut - the red corner, to family and ancestral shrines, and sit down at the table.

Polatny kut - a porch inside a Russian hut. Any kind person can enter there without asking, without knocking on the door. The planks rest on the wall directly above the door with one edge, and on the canvas beam with the other. For this plated beam, the guest, at his will, is not allowed to go. Only the hostess can invite him to enter the next kut - the red corner, to family and ancestral shrines, and sit down at the table.

A refectory, consecrated with shrines, that’s what the red corner is.

So the guest masters the whole half of the hut; however, he will never go into the second, far half (behind the pastry beam), the hostess will not invite him there, because the second half is the main sacred part of the Russian hut - the woman's hut and the stove kuta. These two kuts are similar to the altar of the temple, and in fact this is an altar with an oven-throne and ritual objects: a bread shovel, a broom, grips, a kneading bowl. There the fruits of the earth, heaven and peasant labor are transformed into food of a spiritual and material nature. Because for a person of Tradition, food has never been about the number of calories and a set of textures and tastes.

The male part of the family is not allowed into the woman's kut; here the hostess, the big woman, is in charge of everything, gradually teaching future housewives how to perform sacred rites...

Men work most of the time in the field, in the meadow, in the forest, on the water, and in waste industries. In the house, the owner’s place is immediately at the entrance on a bench, in the ward kut, or at the end of the table farthest from the woman’s kut. It is closer to the small shrines of the red corner, further from the center of the Russian hut.

Men work most of the time in the field, in the meadow, in the forest, on the water, and in waste industries. In the house, the owner’s place is immediately at the entrance on a bench, in the ward kut, or at the end of the table farthest from the woman’s kut. It is closer to the small shrines of the red corner, further from the center of the Russian hut.

The housewife's place is in the red corner - at the end of the table from the side of the woman's kut and the oven - she is the priestess of the home temple, she communicates with the oven and the fire of the oven, she starts the kneading bowl and puts the dough in the oven, she takes it out transformed into bread. It is along the semantic vertical of the stove column that it descends through the golbets (a special wooden extension to the stove) into the subfloor, which is also called the golbets. There, in the golbets, in the basement ancestral sanctuary, the habitat of guardian spirits, they keep supplies. It's not so hot in summer, not so cold in winter. The golbets are akin to a cave - the womb of the Mother Earth, from which they come out and into which decaying remains return.

The hostess is in charge, she is in charge of everything in the house, she is in constant communication with the inner (hut) Earth (half-bridge of the hut, half-cabin), with the inner sky (beam-matitsa, ceiling), with the World Tree (stove pillar), connecting them , with the spirits of the dead (the same stove pillar and golbets) and, of course, with the current living representatives of their peasant family tree. It is her unconditional leadership in the house (both spiritual and material) that does not leave empty time for the peasant in a Russian hut, and sends him beyond the boundaries of the home temple, to the periphery of the space illuminated by the temple, to male spheres and affairs. If the housewife (the axis of the family) is smart and strong, the family wheel spins with the desired constancy.

The hostess is in charge, she is in charge of everything in the house, she is in constant communication with the inner (hut) Earth (half-bridge of the hut, half-cabin), with the inner sky (beam-matitsa, ceiling), with the World Tree (stove pillar), connecting them , with the spirits of the dead (the same stove pillar and golbets) and, of course, with the current living representatives of their peasant family tree. It is her unconditional leadership in the house (both spiritual and material) that does not leave empty time for the peasant in a Russian hut, and sends him beyond the boundaries of the home temple, to the periphery of the space illuminated by the temple, to male spheres and affairs. If the housewife (the axis of the family) is smart and strong, the family wheel spins with the desired constancy.

Construction of a Russian hut

Situation old Russian hut full of clear, uncomplicated and strict meaning. There are wide and low benches along the walls, five or six windows are located low above the floor and provide rhythmic illumination rather than flooding with light. Directly above the windows there is a solid black shelf. Above are five to seven unhewn, smoked crowns of a log house; smoke rises here as the black stove is fired. To remove it, there is a smoke pipe above the door leading to the entryway, and in the entryway there is a wooden exhaust pipe that carries the already cooled smoke outside the house. Hot smoke economically warms up and antisepticizes living spaces. Thanks to him, there were no such severe pandemics in Rus' as in Western Europe.

Situation old Russian hut full of clear, uncomplicated and strict meaning. There are wide and low benches along the walls, five or six windows are located low above the floor and provide rhythmic illumination rather than flooding with light. Directly above the windows there is a solid black shelf. Above are five to seven unhewn, smoked crowns of a log house; smoke rises here as the black stove is fired. To remove it, there is a smoke pipe above the door leading to the entryway, and in the entryway there is a wooden exhaust pipe that carries the already cooled smoke outside the house. Hot smoke economically warms up and antisepticizes living spaces. Thanks to him, there were no such severe pandemics in Rus' as in Western Europe.

The ceiling is made of thick and wide blocks (half-logs), and the floor of the bridge is the same. Under the ceiling there is a mighty matrix beam (sometimes two or three).

The Russian hut is divided into kutas by two raven beams (sheet and pie), laid perpendicular to the upper section of the stove column. The pastry beam extends to the front wall of the hut and separates the women's part of the hut (near the stove) from the rest of the space. It is often used to store baked bread.

There is an opinion that the stove column should not break off at the level of the crows, it should rise higher, right under the mother; in this case the cosmogony of the hut would be complete. In the depths of the northern lands, something similar was discovered, only, perhaps, even more significant, statistically reliably duplicated more than once.

In the immediate vicinity of the stove column, between the pastry beam and the mat, the researchers encountered (for some reason no one had seen before) a carved element with a fairly clear, and even symbolic meaning.

In the immediate vicinity of the stove column, between the pastry beam and the mat, the researchers encountered (for some reason no one had seen before) a carved element with a fairly clear, and even symbolic meaning.

The tripartite nature of such images is interpreted by one of the modern authors as follows: the upper hemisphere is the highest spiritual space (the bowl of “heavenly waters”), the receptacle of grace; the lower one is the vault of heaven covering the Earth - our visible world; the middle link is a node, a ventel, the location of the gods who control the flow of grace into our lower world.

In addition, it is easy to imagine him as the upper (inverted) and lower Bereginya, Baba, Goddess with raised hands. In the middle link one can read the familiar horse heads - a symbol of the solar movement in a circle.

The carved element stands on the pastry beam and precisely supports the matrix.

Thus, in the upper level of the hut space, in the center old Russian hut, in the most significant, striking place, which not a single glance will pass by, the missing link is personally embodied - the connection between the World Tree (stove column) and the celestial sphere (matitsa), and the connection in the form of a complex, deeply symbolic sculptural and carved element. It should be noted that it is located immediately on two internal borders of the hut - between the habitable relatively light bottom and the black “heavenly” top, as well as between the common family half of the hut and the sacred altar forbidden for men - the women's and stove kutas.

Thus, in the upper level of the hut space, in the center old Russian hut, in the most significant, striking place, which not a single glance will pass by, the missing link is personally embodied - the connection between the World Tree (stove column) and the celestial sphere (matitsa), and the connection in the form of a complex, deeply symbolic sculptural and carved element. It should be noted that it is located immediately on two internal borders of the hut - between the habitable relatively light bottom and the black “heavenly” top, as well as between the common family half of the hut and the sacred altar forbidden for men - the women's and stove kutas.

It is thanks to this hidden and very timely found element that it is possible to build a series of complementary architectural and symbolic images of traditional peasant cultural objects and structures.

In their symbolic essence, all these objects are one and the same. However, exactly old Russian hut– the most complete, most developed, most in-depth architectural phenomenon. And now, when it seems that she is completely forgotten and safely buried, her time has come again. The Time of the Russian House is coming - literally.

Chicken hut

It should be noted that researchers recognize the Kurna (black, ore) Russian hut as the highest example of material folk culture, in which the smoke from the furnace went directly into the upper part of the internal volume. The high trapezoidal ceiling made it possible to stay in the hut during the fire. The smoke came out of the mouth of the stove directly into the room, spread along the ceiling, and then dropped to the level of the funnel shelves and was pulled out through a fiberglass window cut into the wall, connected to a wooden chimney.

There are several reasons for the long existence of ore huts, and first of all, climatic conditions - high humidity of the area. Open fire and smoke from the stove soaked and dried the walls of the log house, thus, a kind of preservation of the wood occurred, so the life of the black huts was longer. The chicken stove heated the room well and did not require much firewood. It was also convenient for housekeeping. The smoke dried clothes, shoes and fishing nets.

The transition to white stoves brought with it an irreparable loss in the structure of the entire complex of significant elements of the Russian hut: the ceiling was lowered, the windows were raised, the voronets, stove pillar, and golbets began to disappear. The single zoned volume of the hut began to be divided into functional volumes - rooms. All internal proportions were distorted beyond recognition, appearance and gradually old Russian hut ceased to exist, turning into country house with an interior similar to a city apartment. The whole “perturbation”, in fact, degradation, occurred over a hundred years, starting in the 19th century and ending by the middle of the 20th century. The last chicken huts, according to our information, were converted into white ones after the Great Patriotic War, in the 1950s.

But what should we do now? A return to truly smoking huts is possible only as a result of a global or national catastrophe. However, it is possible to return the entire figurative and symbolic structure of the hut, to saturate the Russian country house with it, even in the conditions of technological progress and the ever-increasing well-being of the “Russians”...

To do this, in fact, you just need to start waking up from sleep. A dream inspired by the elite of our people just when the people themselves were creating masterpieces of their culture.

Based on materials from the magazine “Rodobozhie No. 7”

- 6850The part of the hut from the mouth to the opposite wall, the space in which all women’s work related to cooking was carried out, was called stove corner. Here, near the window, opposite the mouth of the stove, in every house there were hand millstones, which is why the corner is also called millstone.

In the corner of the stove there was a bench or counter with shelves inside, used as a kitchen table. On the walls there were observers - shelves for tableware, cabinets. Above, at the level of the shelf-keepers, was located stove beam, on which kitchen utensils were placed and a variety of household items were placed.

The stove corner was considered a dirty place, in contrast to the rest of the clean space of the hut. Therefore, the peasants always sought to separate it from the rest of the room with a curtain made of variegated chintz, colored homespun, or a wooden partition. The corner of the stove, covered by a board partition, formed a small room called a “closet” or “prilub.”

It was an exclusively female space in the hut: here women prepared food and rested after work. During holidays, when many guests came to the house, a second table was placed near the stove for women, where they feasted separately from the men who sat at the table in the red corner. Men, even their own families, could not enter the women’s quarters unless absolutely necessary. The appearance of a stranger there was considered completely unacceptable.

Red corner, like the stove, was an important landmark in the interior space of the hut. In most of European Russia, in the Urals, and Siberia, the red corner was the space between the side and front walls in the depths of the hut, limited by the corner located diagonally from the stove.

The main decoration of the red corner is goddess with icons and a lamp, which is why it is also called "saints". As a rule, everywhere in Russia in the red corner, in addition to the shrine, there is table. All significant events of family life were noted in the red corner. Here, both everyday meals and festive feasts took place at the table, and many calendar rituals took place. During harvesting, the first and last spikelets were placed in the red corner. The preservation of the first and last ears of the harvest, endowed, according to folk legends, with magical powers, promised well-being for the family, home, and entire household. In the red corner, daily prayers were performed, from which any important undertaking began. It is the most honorable place in the house. According to traditional etiquette, a person who came to a hut could only go there at the special invitation of the owners. They tried to keep the red corner clean and elegantly decorated. The name “red” itself means “beautiful”, “good”, “light”. It was decorated with embroidered towels, popular prints, and postcards. The most beautiful household utensils were placed on the shelves near the red corner, the most valuable papers and objects were stored. Everywhere among Russians, when laying the foundation of a house, it was a common custom to place money under the lower crown in all corners, and a larger coin was placed under the red corner.

Some authors associate the religious understanding of the red corner exclusively with Christianity. In their opinion, the only sacred center of the house in pagan times was the stove. God's corner and the oven are even interpreted by them as Christian and pagan centers.

The lower boundary of the living space of the hut was floor. In the south and west of Rus', floors were often made of earthen floors. Such a floor was raised 20-30 cm above ground level, carefully compacted and covered with a thick layer of clay mixed with finely chopped straw. Such floors have been known since the 9th century. Wooden floors are also ancient, but are found in the north and east of Rus', where the climate is harsher and the soil is wetter.

Pine, spruce, and larch were used for floorboards. The floorboards were always laid along the hut, from the entrance to the front wall. They were laid on thick logs, cut into the lower crowns of the log house - crossbars. In the North, the floor was often arranged as double: under the upper “clean” floor there was a lower one - “black”. The floors in the villages were not painted, preserving the natural color of the wood. Only in the 20th century did painted floors appear. But they washed the floor every Saturday and before the holidays, then covering it with rugs.

The upper boundary of the hut served ceiling. The basis of the ceiling was made of matitsa - a thick tetrahedral beam on which the ceiling tiles were laid. Various objects were hung from the motherboard. A hook or ring was nailed here for hanging the cradle. It was not customary for strangers to enter behind the matitsa. The matitsa was associated with ideas about father's house, happiness, good luck. It is no coincidence that when setting off on the road, it was necessary to hold on to the mat.

The ceilings on the motherboard were always laid parallel to the floorboards. Sawdust and fallen leaves were thrown on top of the ceiling. It was impossible to just sprinkle earth on the ceiling - such a house was associated with a coffin. The ceiling appeared in city houses already in the 13th-15th centuries, and in village houses - at the end of the 17th - beginning of the 18th century. But even until the middle of the 19th century, when firing “in black”, in many places they preferred not to install ceilings.

It was important hut lighting. During the day the hut was illuminated with the help of windows. In a hut, consisting of one living space and a vestibule, four windows were traditionally cut: three on the facade and one on the side. The height of the windows was equal to the diameter of four or five crowns of the frame. The windows were cut down by carpenters already in the erected frame. It was inserted into the opening wooden box, to which a thin frame was attached - a window.

The windows in the peasant huts did not open. The room was ventilated through a chimney or door. Only occasionally could a small part of the frame lift up or move to the side. Sash frames that opened outward appeared in peasant huts only at the very beginning of the 20th century. But even in the 40-50s of the 20th century, many huts were built with non-opening windows. They didn’t make winter or second frames either. And in cold weather, the windows were simply covered from the outside to the top with straw, or covered with straw mats. But the large windows of the hut always had shutters. In the old days they were made with single doors.

A window, like any other opening in a house (door, pipe) was considered a very dangerous place. Only light from the street should enter the hut through the windows. Everything else is dangerous for humans. Therefore, if a bird flies into the window - to the deceased, a night knock on the window - the return to the house of the deceased, who was recently taken to the cemetery. In general, the window was universally perceived as a place where communication with the world of the dead takes place.

However, the windows, being “blind”, provided little light. And therefore, even on the sunny day, the hut had to be illuminated artificially. The oldest lighting device is considered to be fireplace- a small recess, a niche in the very corner of the stove (10 X 10 X 15 cm). A hole was made in the upper part of the niche, connected to stove chimney. A burning splinter or smolje (small resinous chips, logs) was placed in the fireplace. Well-dried torch and tar gave a bright and even light. By the light of the fireplace one could embroider, knit and even read while sitting at the table in the red corner. A child was placed in charge of the fireplace, who changed the torch and added tar. And only much later, at the turn of the 19th-20th centuries, did they begin to call a small fireplace brick stove, attached to the main one and connected to its chimney. On such a stove (fireplace) they cooked food in the hot season or additionally heated it in cold weather.

A little later the firelight appeared torch, inserted into secularists. A splinter was a thin sliver of birch, pine, aspen, oak, ash, and maple. To obtain thin (less than 1 cm) long (up to 70 cm) wood chips, the log was steamed in an oven over cast iron with boiling water and split at one end with an ax. The split log was then torn into splinters by hand. They inserted splinters into the lights. The simplest light was a wrought iron rod with a fork at one end and a point at the other. With this tip, the light was stuck into the gap between the logs of the hut. A splinter was inserted into the fork. And for falling embers, a trough or other vessel with water was placed under the light. Such ancient secularists dating back to the 10th century were found during excavations in Staraya Ladoga. Later, lights appeared in which several torches burned at the same time. They remained in peasant life until the beginning of the 20th century.

On major holidays, expensive and rare candles were lit in the hut to provide full light. With candles in the dark they walked into the hallway and went down to the underground. In winter, they threshed on the threshing floor with candles. The candles were greasy and waxy. At the same time, wax candles were used mainly in rituals. Tallow candles, which appeared only in the 17th century, were used in everyday life.

The relatively small space of the hut, about 20-25 sq.m., was organized in such a way that a fairly large family of seven or eight people could comfortably accommodate it. This was achieved due to the fact that each family member knew his place in the common space. Men usually worked and rested during the day in the men's half of the hut, which included a front corner with icons and a bench near the entrance. Women and children were in the women's quarters near the stove during the day.

Each family member knew his place at the table. The owner of the house sat under the icons during a family meal. His eldest son was located at right hand from the father, the second son is on the left, the third is next to his older brother. Children under marriageable age were seated on a bench running from the front corner along the facade. Women ate while sitting on side benches or stools. It was not supposed to violate the established order in the house unless absolutely necessary. The person who violated them could be severely punished.

On weekdays the hut looked quite modest. There was nothing superfluous in it: the table stood without a tablecloth, the walls without decorations. Everyday utensils were placed in the stove corner and on the shelves. On a holiday, the hut was transformed: the table was moved to the middle, covered with a tablecloth, and festive utensils, previously stored in cages, were displayed on the shelves.

Huts were made under the windows shops, which did not belong to the furniture, but formed part of the extension of the building and were fixedly attached to the walls: the board was cut into the wall of the hut at one end, and supports were made on the other: legs, headstocks, headrests. In ancient huts, benches were decorated with an “edge” - a board nailed to the edge of the bench, hanging from it like a frill. Such shops were called “edged” or “with a canopy”, “with a valance”. In a traditional Russian home, benches ran along the walls in a circle, starting from the entrance, and served for sitting, sleeping, and storing various household items. Each shop in the hut had its own name, associated either with the landmarks of the internal space, or with the ideas that had developed in traditional culture about the activity of a man or woman being confined to a specific place in the house (men's, women's shops). Under the benches they stored various items that were easy to get if necessary - axes, tools, shoes, etc. In traditional rituals and in the sphere of traditional norms of behavior, the bench acts as a place in which not everyone is allowed to sit. Thus, when entering a house, especially for strangers, it was customary to stand at the threshold until the owners invited them to come in and sit down. The same applies to matchmakers: they walked to the table and sat on the bench only by invitation. In funeral rituals, the deceased was placed on a bench, but not just any bench, but one located along the floorboards. A long shop is a shop that differs from others in its length. Depending on the local tradition of distributing objects in the space of the house, a long bench could have a different place in the hut. In the northern and central Russian provinces, in the Volga region, it stretched from the conic to the red corner, along the side wall of the house. In the southern Great Russian provinces it ran from the red corner along the wall of the facade. From the point of view of the spatial division of the house, the long shop, like the stove corner, was traditionally considered a women's place, where at the appropriate time they did certain women's work, such as spinning, knitting, embroidery, sewing. The dead were placed on a long bench, always located along the floorboards. Therefore, in some provinces of Russia, matchmakers never sat on this bench. Otherwise, their business could go wrong. A short bench is a bench that runs along the front wall of a house facing the street. During family meals, men sat on it.

The shop located near the stove was called kutnaya. Buckets of water, pots, cast iron pots were placed on it, and freshly baked bread was placed on it.

The threshold bench ran along the wall where the door was located. It was used by women instead of a kitchen table and differed from other benches in the house in the absence of an edge along the edge.

A bench is a bench that runs from the stove along the wall or door partition to the front wall of the house. The surface level of this bench is higher than other benches in the house. The bench at the front has folding or sliding doors or can be closed with a curtain. Inside there are shelves for dishes, buckets, cast iron pots, and pots. Konik was the name for a men's shop. It was short and wide. In most of Russia, it took the form of a box with a hinged flat lid or a box with sliding doors. The konik probably got its name from the horse’s head carved from wood that adorned its side. Konik was located in the residential part of the peasant house, near the door. It was considered a "men's" shop because it was a men's workplace. Here they were engaged in small crafts: weaving bast shoes, baskets, repairing harnesses, knitting fishing nets, etc. Under the bunk were also the tools necessary for these works. A place on a bench was considered more prestigious than on a bench; the guest could judge the attitude of the hosts towards him, depending on where he was seated - on a bench or on a bench.

A necessary element of home decoration was a table that served for daily and holiday meals. The table was one of the most ancient types of movable furniture, although the earliest tables were made of adobe and fixed. Such a table with adobe benches around it were discovered in Pronsky dwellings of the 11th-13th centuries (Ryazan province) and in a Kyiv dugout of the 12th century. The four legs of a table from a dugout in Kyiv are racks dug into the ground. In a traditional Russian home, a movable table always had permanent place, he stood in the most honorable place - in the red corner, in which the icons were located. In Northern Russian houses, the table was always located along the floorboards, that is, with the narrower side towards the front wall of the hut. In some places, for example in the Upper Volga region, the table was placed only for the duration of the meal; after eating it was placed sideways on a shelf under the images. This was done so that there was more space in the hut.

In the forest zone of Russia, carpentry tables had a unique shape: a massive underframe, that is, a frame connecting the legs of the table, was covered with boards, the legs were made short and thick, the large tabletop was always made removable and protruded beyond the underframe in order to make it more comfortable to sit. Under the table there was a cabinet with double doors for tableware and bread needed for the day. In traditional culture, in ritual practice, in the sphere of behavioral norms, etc., the table was given great importance. This is evidenced by its clear spatial location in the red corner. Any promotion of him from there can only be associated with a ritual or crisis situation. The exclusive role of the table was expressed in almost all rituals, one of the elements of which was a meal. It manifested itself with particular brightness in the wedding ceremony, in which almost every stage ended with a feast. The table was conceptualized in the popular consciousness as “God’s palm”, giving daily bread, therefore knocking on the table at which one eats was considered a sin. In ordinary, non-feast times, only bread, usually wrapped in a tablecloth, and a salt shaker could be on the table.

In the sphere of traditional norms of behavior, the table has always been a place where the unity of people took place: a person who was invited to dine at the master’s table was perceived as “one of our own.”

The table was covered with a tablecloth. In the peasant hut, tablecloths were made from homespun, both simple plain weave and made using the technique of bran and multi-shaft weaving. Tablecloths used every day were sewn from two motley panels, usually with a checkered pattern (the colors are very varied) or simply rough canvas. This tablecloth was used to cover the table during lunch, and after eating it was either removed or used to cover the bread left on the table. Holiday tablecloths were different best quality fabrics, such additional details as lace stitching between two panels, tassels, lace or fringe around the perimeter, as well as a pattern on the fabric. In Russian life, the following types of benches were distinguished: saddle bench, portable bench and extension bench. Saddle bench - a bench with a folding backrest ("saddleback") was used for sitting and sleeping. If it was necessary to arrange a sleeping place, the backrest along the top, along the circular grooves made in the upper parts of the side stops of the bench, was thrown to the other side of the bench, and the latter was moved towards the bench, so that a kind of bed was formed, limited in front by a “crossbar”. The back of the saddle bench was often decorated through thread, which significantly reduced its weight. This type of bench was used mainly in urban and monastic life.

Portable bench- a bench with four legs or two blank boards, as needed, attached to the table, used for sitting. If there was not enough sleeping space, the bench could be moved and placed along the bench to increase space for an additional bed. Portable benches were one of the oldest forms of furniture among the Russians.

An extension bench is a bench with two legs, located only at one end of the seat; the other end of such a bench was placed on a bench. Often this type of bench was made from a single piece of wood in such a way that the legs were two tree roots, cut to a certain length. The dishes were placed in shelves: these were pillars with numerous shelves between them. On the lower, wider shelves, massive dishes were stored; on the upper, narrower shelves, small dishes were placed.

A crockery dish was used to store separately used dishes: a wooden shelf or an open shelf cabinet. The vessel could have the shape of a closed frame or be open at the top, often its side walls decorated with carvings or had figured shapes (for example, oval). Above one or two shelves of the dishware, a rail could be nailed on the outside to stabilize the dishes and to place the plates on edge. As a rule, the dishware was located above the ship's bench, at hand at the hostess. He has long been necessary part in the motionless decoration of the hut.

The red corner was also decorated with a shroud, a rectangular piece of fabric sewn from two pieces of white thin canvas or chintz. The dimensions of the shroud can be different, usually 70 cm long, 150 cm wide. White shrouds were decorated along the lower edge with embroidery, woven patterns, ribbons, and lace. The shroud was attached to the corner under the images. At the same time, the shrines or icons were girded with a shrine on top. For the festive decoration of the hut, a towel was used - a sheet of white fabric, home-made or, less often, factory-made, trimmed with embroidery, a woven colored pattern, ribbons, stripes of colored calico, lace, sequins, braid, braid, fringe. It was decorated, as a rule, at the ends. The panel of the towel was rarely ornamented. The nature and quantity of decorations, their location, color, material - all this was determined by local tradition, as well as the purpose of the towel. In addition, towels were hung during weddings, at a christening dinner, on the day of a meal on the occasion of a son’s return from military service or the arrival of long-awaited relatives. Towels were hung on the walls that made up the red corner of the hut, and in the red corner itself. They were put on wooden nails - “hooks”, “matches”, driven into the walls. According to custom, towels were a necessary part of a girl's trousseau. It was customary to show them to the husband's relatives on the second day of the wedding feast. The young woman hung towels in the hut on top of her mother-in-law’s towels so that everyone could admire her work. The number of towels, the quality of the linen, the skill of embroidery - all this made it possible to appreciate the hard work, neatness, and taste of the young woman. The towel generally played a big role in the ritual life of the Russian village. It was an important attribute of wedding, birth, funeral and memorial rituals. Very often it acted as an object of veneration, an object of special importance, without which the ritual of any ceremony would not be complete. On the wedding day, the towel was used by the bride as a veil. Throwed over her head, it was supposed to protect her from the evil eye and damage at the most crucial moment of her life. The towel was used in the ritual of “union of the newlyweds” before the crown: they tied the hands of the bride and groom “forever and ever, for many years to come.” The towel was given to the midwife who delivered the baby, and to the godfather and godmother who baptized the baby. The towel was present in the “babina porridge” ritual that took place after the birth of a child.

However, the towel played a special role in funeral and memorial rituals. According to legends, a towel hung on the window on the day of a person’s death contained his soul for forty days. The slightest movement of the fabric was seen as a sign of its presence in the house. In the forties, the towel was shaken outside the village, thereby sending the soul from “our world” to the “other world.” All these actions with the towel were widespread in the Russian village. They were based on ancient mythological ideas of the Slavs. In them, the towel acted as a talisman, a sign of belonging to a certain family group, and was interpreted as an object that embodied the souls of the ancestors of the “parents” who carefully observed the lives of the living. This symbolism of the towel excluded its use for wiping hands, face, and floor. For this purpose, they used a rukoternik, a wiping machine, a wiping machine, etc.

Utensil

Utensils are utensils for preparing, preparing and storing food, serving it on the table; various containers for storing household items and clothing; items for personal hygiene and home hygiene; items for starting a fire, for cosmetics. In the Russian village, mainly wooden pottery utensils were used. Metal, glass, and porcelain were less common. According to the manufacturing technique, wooden utensils could be chiseled, hammered, cooper's, carpentry, or lathe. Utensils made from birch bark, woven from twigs, straw, and pine roots were also in great use. Some of the wooden items needed in the household were made by the male half of the family. Most of the items were purchased at fairs and markets, especially for cooperage and turning utensils, the manufacture of which required special knowledge and tools. Pottery was used mainly for cooking food in an oven and serving it on the table, sometimes for salting and fermenting vegetables. Metal utensils of the traditional type were mainly copper, tin or silver. Its presence in the house was a clear indication of the family’s prosperity, its thriftiness, and respect for family traditions. Such utensils were sold only at the most critical moments of a family’s life. The utensils that filled the house were made, purchased, and stored by Russian peasants, naturally based on their purely practical use. However, in some cases, from the point of view of the peasant important points In life, almost every one of its objects turned from a utilitarian thing into a symbolic one. At one point during the wedding ceremony, the dowry chest turned from a container for storing clothes into a symbol of the family’s prosperity and the bride’s hard work. A spoon with the scoop facing up meant that it would be used at a funeral meal. An extra spoon on the table foreshadowed the arrival of guests, etc. Some utensils had a very high semiotic status, others a lower one. Bodnya, an item of household utensils, was a wooden container for storing clothes and small items household items. In the Russian village, two types of bodny were known. The first type was a long hollowed-out wooden log, the side walls of which were made of solid boards. A hole with a lid on leather hinges was located at the top of the deck. Bodnya of the second type is a dugout or cooper's tub with a lid, 60-100 cm high, bottom diameter 54-80 cm. Bodnya were usually locked and stored in cages. From the second half of the 19th century. began to be replaced by chests.

To store bulky household supplies in cages, barrels, tubs, and baskets were used different sizes and volume. In the old days, barrels were the most common container for both liquids and bulk solids, for example: grain, flour, flax, fish, dried meat, horse meat and various small goods.

To prepare pickles, pickles, soaks, kvass, water for future use, and to store flour and cereals, tubs were used. As a rule, the tubs were made by coopers, i.e. were made from wooden planks - rivets, fastened with hoops. they were made in the shape of a truncated cone or cylinder. they could have three legs, which were a continuation of the rivets. The necessary accessories for the tub were a circle and a lid. The food placed in the tub was pressed in a circle, and oppression was placed on top. This was done so that the pickles and pickles were always in the brine and did not float to the surface. The lid protected food from dust. The mug and lid had small handles. Lukoshkom was an open cylindrical container made of bast, with a flat bottom, made of wooden planks or bark. It was done with or without a spoon handle. The size of the basket was determined by its purpose and was called accordingly: “nabirika”, “bridge”, “berry”, “mycelium”, etc. If the basket was intended for storing bulk products, it was closed with a flat lid placed on top. For many centuries, the main kitchen vessel in Rus' was a pot - a cooking utensil in the form of a clay vessel with a wide open top, having a low rim, a round body, smoothly tapering towards bottom. Pots could be different sizes: from a small pot for 200-300 g of porridge to a huge pot that could hold up to 2-3 buckets of water. The shape of the pot did not change throughout its existence and was well suited for cooking in a Russian oven. They were rarely ornamented; they were decorated with narrow concentric circles or a chain of shallow dimples and triangles pressed around the rim or on the shoulders of the vessel. In the peasant house there were about a dozen or more pots of different sizes. They treasured the pots and tried to handle them carefully. If it cracked, it was braided with birch bark and used for storing food.

Pot- an everyday, utilitarian object, in the ritual life of the Russian people acquired additional ritual functions. Scientists believe that this is one of the most ritualized household utensils. In popular beliefs, a pot was conceptualized as a living anthropomorphic creature that had a throat, a handle, a spout, and a shard. Pots are usually divided into pots that carry a feminine essence, and pots with a masculine essence embedded in them. Thus, in the southern provinces of European Russia, the housewife, when buying a pot, tried to determine its gender: whether it was a pot or a potter. It was believed that food cooked in a pot would be more tasty than in a pot. It is also interesting to note that in the popular consciousness there is a clear parallel between the fate of the pot and the fate of man. The pot found quite wide application in funeral rituals. Thus, in most of the territory of European Russia, the custom of breaking pots when removing the dead from the house was widespread. This custom was perceived as a statement of a person’s departure from life, home, or village. In Olonets province. this idea was expressed somewhat differently. After the funeral, a pot filled with hot coals in the deceased’s house was placed upside down on the grave, and the coals scattered and went out. In addition, the deceased was washed with water taken from a new pot two hours after death. After consumption, it was taken away from the house and buried in the ground or thrown into water. It was believed that the last life force a person, which is drained while washing the deceased. If such a pot is left in the house, the deceased will return from the other world and frighten the people living in the hut. The pot was also used as an attribute of some ritual actions at weddings. So, according to custom, the “wedding celebrants,” led by groomsmen and matchmakers, came in the morning to break pots to the room where the wedding night of the newlyweds took place, before they left. Breaking pots was perceived as demonstrating a turning point in the fate of a girl and a guy who became a woman and a man. Among the Russian people, the pot often acts as a talisman. In Vyatka province, for example, to protect chickens from hawks and crows, they hung them upside down on the fence old pot. This was done without fail on Maundy Thursday before sunrise, when witchcraft spells were especially strong. In this case, the pot seemed to absorb them into itself and receive additional magical power.

To serve food on the table, such tableware was used as a dish. It was usually round or oval in shape, shallow, on a low tray, with wide edges. Wooden dishes were mainly common in everyday life. Dishes intended for holidays were decorated with paintings. They depicted plant shoots, small geometric figures, fantastic animals and birds, fish and skates. The dish was used both in everyday and festive life. On weekdays, fish, meat, porridge, cabbage, cucumbers and other “thick” dishes were served on a platter, eaten after soup or cabbage soup. On holidays, in addition to meat and fish, pancakes, pies, buns, cheesecakes, gingerbread cookies, nuts, candies and other sweets were served on the platter. In addition, there was a custom to serve guests a glass of wine, mead, mash, vodka or beer on a platter. The horses of the festive meal were indicated by bringing out an empty dish, covered with another or a cloth. The dishes were used during folk ritual actions, fortune telling, and magical procedures. In maternity rituals, a dish of water was used during the ritual of magical cleansing of the woman in labor and the midwife, which was carried out on the third day after childbirth. The woman in labor “silvered her grandmother,” i.e. threw silver coins into the water poured by the midwife, and the midwife washed her face, chest and hands. In the wedding ceremony, the dish was used for public display of ritual objects and the presentation of gifts. The dish was also used in some rituals of the annual cycle. The dish was also an attribute of the girls’ Christmas fortune-telling, called “podblyudnye”. In the Russian village there was a ban on its use on some days of the folk calendar. A bowl was used for drinking and eating. The wooden bowl is a hemispherical vessel with small pallet, sometimes with handles or rings instead of handles, without a lid. Often an inscription was made along the edge of the bowl. Either along the crown or along the entire surface, the bowl was decorated with paintings, including floral and zoomorphic ornaments (bowls with Severodvinsk painting are widely known). Bowls of various sizes were made, depending on their use. Large bowls, weighing up to 800 g or more, were used along with scrapers, brothers and ladles during holidays and eves for drinking beer and mash, when many guests gathered. In monasteries, large bowls were used to serve kvass to the table. Small bowls, hollowed out of clay, were used in peasant life during lunch - for serving cabbage soup, stew, fish soup, etc. During lunch, food was served on the table in a common bowl; separate dishes were used only during holidays. They began to eat at a sign from the owner; they did not talk while eating. Guests who entered the house were treated to the same thing that they ate themselves, and from the same dishes.

The cup was used in various rituals, especially in life cycle rituals. It was also used in calendar rituals. Signs and beliefs were associated with the cup: at the end of the festive dinner, it was customary to drink the cup to the bottom for the health of the host and hostess; those who did not do this were considered an enemy. Draining the cup, they wished the owner: “Good luck, victory, health, and that there would be no more blood left in his enemies than in this cup.” The cup is also mentioned in conspiracies. A mug was used to drink various drinks.

A mug is a cylindrical container of varying volume with a handle. Clay and wood mugs were decorated with paintings, and wooden mugs were decorated with carvings; the surface of some mugs was covered with birch bark weaving. They were used in everyday and festive life, and they were also the subject of ritual actions. A glass was used to drink intoxicating drinks. It is a small round-shaped vessel with a leg and a flat bottom, sometimes there could be a handle and a lid. The glasses were usually painted or decorated with carvings. This vessel was used as an individual vessel for drinking mash, beer, intoxicated mead, and later wine and vodka on holidays, since drinking was allowed only on holidays and such drinks were a festive treat for guests. It was accepted to drink for the health of other people, and not for oneself. When presenting a glass of wine to a guest, the host expected a glass of wine in return. The glass was most often used in wedding ceremonies. The priest offered a glass of wine to the newlyweds after the wedding. They took turns taking three sips from this glass. Having finished the wine, the husband threw the glass under his feet and trampled it at the same time as his wife, saying: “Let those who begin to sow discord and dislike among us be trampled under our feet.” It was believed that whichever spouse stepped on it first would dominate the family. The owner presented the first glass of vodka at the wedding feast to the sorcerer, who was invited to the wedding as an honored guest in order to save the newlyweds from damage. The sorcerer asked for the second glass himself and only after that began to protect the newlyweds from evil forces.

Until forks appeared, the only utensils for eating were spoons. They were mostly wooden. Spoons were decorated with paintings or carvings. Various signs associated with spoons were observed. It was impossible to place the spoon so that it rested with its handle on the table and the other end on the plate, since evil spirits could penetrate along the spoon, like across a bridge, into the bowl. It was not allowed to knock spoons on the table, as this would make “the evil one rejoice” and “the evil ones would come to dinner” (creatures personifying poverty and misfortune). It was considered a sin to remove spoons from the table on the eve of the fasts prescribed by the church, so the spoons remained on the table until the morning. You cannot put an extra spoon, otherwise there will be an extra mouth or evil spirits will sit at the table. As a gift, you had to bring a spoon for a housewarming, along with a loaf of bread, salt and money. The spoon was widely used in ritual actions.

Traditional utensils for Russian feasts were valleys, ladles, bratins, and brackets. Valley valleys were not considered valuable items that needed to be displayed at the most the best place in the house, as, for example, was done with brother or ladles.

A poker, a grip, a frying pan, a bread shovel, a broom - these are objects associated with the hearth and stove.

Poker- This is a short, thick iron rod with a curved end, which was used to stir coals in the stove and rake up the heat. Pots and cast iron pots were moved in the oven with the help of a grip; they could also be removed or installed in the oven. It consists of a metal bow mounted on a long wooden handle. Before planting the bread in the oven, coal and ash were cleared from under the oven by sweeping it with a broom. A broomstick is a long wooden handle, to the end of which pine, juniper branches, straw, a washcloth or a rag were tied. Using a bread shovel, they put bread and pies into the oven, and also took them out of there. All these utensils participated in certain ritual actions. Thus, the Russian hut, with its special, well-organized space, fixed decoration, movable furniture, decoration and utensils, was a single whole, constituting the whole world.

Residents of villages in Ancient Rus' built wooden huts. Since there was plenty of forest in the country, everyone could stock up on logs. Over time, a full-fledged house-building craft arose and began to develop.

So by the 16th century. In princely Moscow, districts filled with log houses were formed that were ready for sale. They were transported to the capital of the principality along the river and sold at low prices, which made foreigners surprised at the cost of such housing.

To repair the hut, only logs and boards were required. Depending on the required dimensions, it was possible to select a suitable log house and immediately hire carpenters who would assemble the house.

Log cabins have always been in high demand. Due to frequent massive fires, cities (sometimes even due to careless handling of fire) and villages had to be rebuilt. Enemy raids and internecine wars caused great damage.

How were huts built in Rus'?

The logs were laid in such a way that they were connected to each other at all 4 corners. There were two types of wooden buildings: summer (cold) and winter (equipped with a stove or hearth).

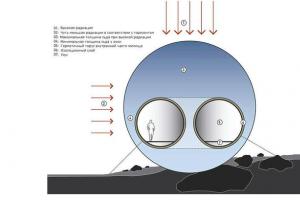

1. To save wood, they used semi-earth technology, when the lower part was dug in the ground, and on top there was a cage with windows (they were tightened bullish bubble or covered with a lid-shutter).

For such housing, light, sandy, not saturated soil was more preferable. The walls of the pit were lined with boards and sometimes coated with clay. If the floor was compacted, then it was also treated with a clay mixture.

2. There was another way - laying a finished pine frame in the dug up ground. Crushed stones, stones and sand were poured between the walls of the pit and the future house. There were no structures inside the floor. And there was no ceiling as such either. There was a roof covered with straw and dry grass and branches, which was supported on thick poles. The standard area of the hut was approximately 16 square meters. m.

3. The wealthier peasants of Ancient Rus' built houses that were completely above the ground and had a roof covered with boards. A mandatory attribute of such housing was a stove. In the attic, rooms were organized that were mainly used for household needs. Fiberglass windows were cut into the walls. They were ordinary openings, which in the cold season were covered with shields made of boards, that is, “clouded.”

Until the 14th century. in the huts of wealthy residents (peasants, nobles, boyars), the windows were made not of fiberglass, but of mica. Over time, glass replaced mica plates. However, back in the 19th century. in villages window glass were a great and valuable rarity.

How did they live in Russian huts?

In Rus', huts were very practical housing, which were installed in such a way as to retain heat. The entrance to the house was on the south side; there was a blank wall on the north side. The space was divided into 2 parts: cold and warm cages, their area was not the same. The first housed livestock and equipment; the warm one was equipped with a stove or hearth, and a bed was placed for rest.

Russian huts were heated in a black way: smoke swirled across the floor and came out of the door, which is why the ceiling and walls were covered with a thick layer of soot. In wealthy houses, the firebox was done in a white way, that is, through a chimney in the stove.

In the houses of the boyars, an additional third floor was built - the chamber. As a rule, chambers for the wife or daughters were located there. The type of wood that was used in the construction of housing was important. Representatives of the upper class chose oak as it was considered the most durable material. The rest built buildings from pine logs.

Old Russian mansions

In Rus', mansions were called huts from wooden log house, which consisted of several buildings connected to each other. Together the buildings formed the prince's court.

Each component had its name:

- false - sleeping area;

- medusha - a pantry for storing supplies of honey and mash;

- soap house - a room for washing, a bathhouse;

- gridnitsa - front hall for receiving guests.

Decoration of an ancient Russian hut

The furnishings and interior of the wooden hut were organized in compliance with traditions. Most of the space was given to the stove, which was located on the right or left side of the entrance. This attribute performed several functions at once: they slept on it, cooked food in the stove, and when there was no separate bathhouse in the yard, they also washed in the stove!

A red corner was placed opposite the stove (diagonally) - a place for the owner and guests of honor. There was also a place for icons and shrines that protected the home.

The corner opposite the stove was a kitchen space, which was called a woman's kut. The peasant women stayed at the stove for long evenings: in addition to cooking, they did handicrafts there - sewing and spinning by the light of a torch.

The men's kut had its own household chores: they repaired equipment, wove bast shoes, etc.

The huts were furnished with the simplest furniture - benches, tables. They slept on palats - wide benches installed high near the wall of the stove.

Peasant houses were not decorated with decorative elements. In the princes' chambers, carpets, animal skins and weapons were hung on the walls.

A child is not a vessel that needs to be filled, but a fire that needs to be lit.

The table is decorated by the guests, and the house by the children.

He who does not abandon his children does not die.

Be truthful even towards a child: keep your promise, otherwise you will teach him to lie.

— L.N. Tolstoy

Children need to be taught to speak and adults to listen to children.

Let childhood mature in children.

Life needs to be interrupted more often so that it doesn’t turn sour.

— M. Gorky

Children need to be given not only life, but also the opportunity to live.

Not the father-mother who gave birth, but the one who gave him water, fed him, and taught him goodness.

Interior arrangement of a Russian hut

The hut was the most important keeper of family traditions for the Russian people; a large family lived here and children were raised. The hut was a symbol of comfort and tranquility. The word “izba” comes from the word “to heat.” The furnace is the heated part of the house, hence the word “istba”.

The interior decoration of a traditional Russian hut was simple and comfortable: a table, benches, benches, stoltsy (stools), chests - everything was done in the hut with your own hands, carefully and with love, and was not only useful, beautiful, pleasing to the eye, but carried its own protective properties. For good owners, everything in the hut was sparkling clean. There are embroidered white towels on the walls; the floor, table, benches were scrubbed.

There were no rooms in the house, so all the space was divided into zones, according to functions and purpose. The separation was made using a kind of fabric curtain. In this way, the economic part was separated from the residential part.

The central place in the house was reserved for the stove. The stove sometimes occupied almost a quarter of the hut, and the more massive it was, the more heat it accumulated. The internal layout of the house depended on its location. That’s why the saying arose: “Dancing from the stove.” The stove was an integral part not only of the Russian hut, but also of Russian tradition. It served simultaneously as a source of heat, a place for cooking, and a place for sleeping; used in the treatment of most various diseases. In some areas people washed and steamed in the oven. The stove, at times, personified the entire home; its presence or absence determined the nature of the building (a house without a stove is non-residential). Cooking food in a Russian oven was a sacred act: raw, unmastered food was transformed into boiled, mastered food. The stove is the soul of the home. The kind, honest Mother Oven, in whose presence they did not dare to say a swear word, under which, according to the beliefs of their ancestors, the keeper of the hut, the Brownie, lived. Rubbish was burned in the stove, since it could not be taken out of the hut.

The place of the stove in a Russian house can be seen by the respect with which the people treated their hearth. Not every guest was allowed to the stove, but if they allowed someone to sit on their stove, then such a person became especially close and welcome in the house.

The stove was installed diagonally from the red corner. This was the name for the most elegant part of the house. The word “red” itself means: “beautiful”, “good”, “light”. The red corner was located opposite front door so that everyone who enters can appreciate the beauty. The red corner was well lit, since both of its constituent walls had windows. They treated the decoration of the red corner with particular care and tried to keep it clean. It was the most honorable place in the house. Particularly important family values, amulets, and idols were located here. Everything was placed on a shelf or table lined with an embroidered towel, in a special order. According to tradition, a person who came to the hut could only go there at the special invitation of the owners.

As a rule, everywhere in Russia there was a table in the red corner. In a number of places it was placed in the wall between the windows - opposite the corner of the stove. The table has always been a place where family members come together.

In the red corner, near the table, two benches meet, and on top there are two shelves of a shelf holder. All significant events of family life were noted in the red corner. Here, at the table, both everyday meals and festive feasts took place; Many calendar rituals took place. In the wedding ceremony, the matchmaking of the bride, her ransom from her girlfriends and brother took place in the red corner; they took her away from the red corner of her father’s house; They brought him to the groom’s house and also led him to the red corner.

Opposite the red corner there was a stove or “woman’s” corner (kut). There the women prepared food, spun, weaved, sewed, embroidered, etc. Here, near the window, opposite the mouth of the stove, in every house there were hand millstones, which is why the corner is also called a millstone. On the walls there were observers - shelves for tableware, cabinets. Above, at the level of the shelf holders, there was a stove beam, on which kitchen utensils were placed, and various household utensils were stacked. The corner of the stove, closed by a board partition, formed a small room called a “closet” or “prilub.” It was a kind of women's space in the hut: here women prepared food and rested after work.

The relatively small space of the hut was organized in such a way that a fairly large family of seven or eight people could comfortably accommodate it. This was achieved due to the fact that each family member knew his place in the common space. The men worked and rested during the day in the men's half of the hut, which included the front corner and a bench near the entrance. Women and children spent the day in the women's quarters near the stove. Places for sleeping at night were also allocated. Sleeping places were located on benches and even on the floor. Under the very ceiling of the hut, between two adjacent walls and the stove, a wide plank platform was laid on a special beam - “polati”. Children especially loved to sit on the beds - it was warm and you could see everything. Children, and sometimes adults, slept on the floors; clothes were also stored here; onions, garlic and peas were dried here. A baby cradle was secured under the ceiling.

All household belongings were stored in chests. They were massive, heavy, and sometimes reached such sizes that an adult could easily sleep on them. Chests were made to last for centuries, so they were reinforced at the corners with forged metal; such furniture lived in families for decades, passed down by inheritance.

In a traditional Russian home, benches ran along the walls in a circle, starting from the entrance, and served for sitting, sleeping, and storing various household items. In ancient huts, benches were decorated with an “edge” - a board nailed to the edge of the bench, hanging from it like a frill. Such benches were called “edged” or “with a canopy”, “with a valance. Under the benches they kept various items that, if necessary, were easy to get: axes, tools, shoes, etc. In traditional rituals and in the sphere of traditional norms of behavior, a bench acts as a place in which not everyone is allowed to sit. Thus, when entering a house, especially strangers, it was customary to stand at the threshold until the owners invited them to come in and sit down. The same applies to matchmakers - they walked to the table and sat down to the shop by invitation only.

There were many children in the Russian hut, and the cradle was as necessary an attribute of the Russian hut as a table or stove. Common materials for making cradles were bast, reeds, pine shingles, and linden bark. More often the cradle was hung in the back of the hut, next to the flood. A ring was driven into a thick ceiling log, a “jock” was hung on it, onto which the cradle was attached with ropes. It was possible to rock such a cradle using a special strap with your hand, or if your hands were busy, with your foot. In some regions, the cradle was hung on an ochep - a rather long wooden pole. Most often, well-bending and springy birch was used for ochepa. Hanging the cradle from the ceiling was not accidental: the most warm air, which provided warmth for the child. There was a belief that heavenly forces protect a child raised above the floor, so he grows better and accumulates vital energy. The floor was perceived as the border between the human world and the world where evil spirits live: the souls of the dead, ghosts, brownies. To protect the child from them, amulets were always placed under the cradle. And on the head of the cradle they carved the sun, in the legs there was a month and stars, multi-colored rags and painted wooden spoons were attached. The cradle itself was decorated with carvings or paintings. A mandatory attribute was a canopy. The most beautiful fabric was chosen for the canopy; it was decorated with lace and ribbons. If the family was poor, they used an old sundress, which, despite the summer, looked elegant.

In the evenings, when it got dark, Russian huts were illuminated by torches. The torch was the only source of lighting in the Russian hut for many centuries. Usually, birch was used as a torch, which burned brightly and did not smoke. A bunch of splinters was inserted into special forged lights that could be fixed anywhere. Sometimes they used oil lamps - small bowls with edges curved up.

The curtains on the windows were plain or patterned. They were woven from natural fabrics and decorated with protective embroidery. White lace self made All textile items were decorated: tablecloths, curtains and sheet valance.

On a holiday, the hut was transformed: the table was moved to the middle, covered with a tablecloth, and festive utensils, previously stored in cages, were displayed on the shelves.

As the main color range for the hut, golden ocher was used, with the addition of red and white flowers. Furniture, walls, dishes, painted in golden ocher tones, were successfully complemented by white towels, red flowers, and beautiful paintings.

The ceiling could also be painted with floral patterns.

Thanks to the exclusive use natural materials During construction and interior decoration, the huts were always cool in summer and warm in winter.

In the setting of the hut there was not a single unnecessary random object; each thing had its strictly defined purpose and a place illuminated by tradition, which is a distinctive feature of the character of the Russian home.

Russian national housing - in Russian traditional culture, which was widely used back in the late 19th - early 20th centuries, was a structure made of wood - a hut, built using log or frame technology.

The basis of the Russian national dwelling is a cage, a rectangular covered one-room simple log house without extensions (log house) or hut. The dimensions of the cages were small, 3 by 2 meters, and there were no window openings. The height of the cage was 10-12 logs. The cage was covered with straw. A cage with a stove is already a hut.

How did our ancestors choose places to live and building materials for their homes?

Settlements often arose in wooded areas, along the banks of rivers and lakes, since waterways were then natural roads that connected numerous cities of Rus'. In the forest there are animals and birds, resin and wild honey, berries and mushrooms, “To live near the forest, you won’t go hungry” they said in Rus'. Previously, the Slavs conquered living space from the forest, cutting and cultivating the cornfield. Construction began with the felling of forests and a settlement - a “village” - appeared on the cleared land. The word “village” is derived from the word “derv” (from the action “d’arati”) - something that is torn out by the roots (forest and thickets). It didn't take a day or two to build. First it was necessary to develop the site. They prepared the land for arable land, cut down, and uprooted the forest. This is how “zaimka” arose (from the word “to borrow”), and the first buildings were called “repairs” (from the word “initial”, i.e. beginning). Relatives and just neighbors settled nearby (those who “sat down” nearby). To build a house, our ancestors cut down coniferous trees (the most resistant to decay) and took only those that fell with their tops to the east. Young and old trees, as well as dead wood, were unsuitable for this. Single trees and groves that grew on the site of a destroyed church were considered sacred, so they were also not taken to build a house. They cut it down in cold weather because the tree was considered dead at that time (wood is drier at this time). They chopped it down, not sawed it: it was believed that the tree would be better preserved this way. The logs were stacked, the bark was removed from them in the spring, they were leveled, collected in small log houses and left to dry until the fall, and sometimes until the following spring. Only after this did they begin to select a location and build a house. This was the experience of centuries-old wooden construction.

“The hut is not cut for summer, but for winter” - what was the name of the peasant log house and how did they choose the place for it?

The most ancient and simplest type of Russian buildings consists of “cages” - small tetrahedral log houses. One of the cages was heated by a “hearth” and therefore was called “istba”, from the word “istobka”, hence the name of the Russian house - “izba”. IZBA is a wooden (log) log residential building. Large houses were built, grandfathers and fathers, grandchildren and great-grandchildren all lived together under one roof - “A family is strong when there is only one roof over it.” The hut was usually cut from thick logs, stacking them in a log house. The log house consisted of “crowns”. The crown is four logs laid horizontally in a square or rectangle and connected at the corners with notches (recesses so that the logs “sit” tightly on top of one another). From the ground to the roof, about 20 such “crowns” had to be assembled. The most reliable and warmest was considered to be the fastening of logs “in the oblo” (from the word “obly” - round), in which the round log ends of the logs were cut into each other and they came out a little outside the wall, the corners of such a house did not freeze. The logs of the log house were tied together so tightly that even a knife blade could not pass between them. The location for the house was chosen very carefully. They never built a hut on the site of an old one if the previous housing burned down or collapsed due to troubles. In no case was a hut built “on blood” or “on bones” - where even a drop of human blood fell on the ground or bones were found, this happened! A place where a cart once overturned (there will be no wealth in the house), or where a road once passed (misfortunes could come to the house along it), or where a crooked tree grew, was considered bad. People tried to notice where the cattle liked to rest: this place promised good luck to the owners of the house built there.

What are the names of the main elements of the decorative decoration of a hut?

1. “The Little Horse” is a talisman for the home against evil forces. The horse was hewn out of a very thick tree, which was dug up by the roots, the root was processed, giving it the appearance of a horse's head. Skates look into the sky and protect the house not only from bad weather. In ancient times, the horse was a symbol of the sun; according to ancient beliefs, the sun was carried across the sky by winged invisible horses, so they piled the horse on the roof to support the sun. 2. From under the ridge descended a skillfully carved board - “Towel”, so named for its resemblance to the embroidered end of a real towel and symbolizing the sun at its zenith; to the left of it the same board symbolized the sunrise, and to the right it symbolized sunset. 3. The facade of the house is a wall facing the street - it was likened to a person’s face. There were windows on the façade. The word "window" comes from ancient name eyes - “eye”, and windows were considered the eyes on the face of the house, so wooden carved decorations windows are called “platbands”. Often the windows were supplemented with “shutters”. In the southern huts you could reach the windows with your hands, but in the north the houses were placed on a high “basement” (that is, what is under the cage). Therefore, to close the shutters, special bypass galleries were arranged - “gulbishchas”, which encircled the house at the level of the windows. Windows used to be closed with mica or bull's bubbles; glass appeared in the 14th century. Such a window let in little light, but in winter the hut retained heat better. 4. Roof of the house from the front and back walls in the form of log triangles symbolized the “forehead” on the face of the house, the Old Russian name for the forehead sounds like “chelo”, and the carved boards protruding from under the roof are “Prichelina”.

What did the upper and lower boundaries in the living space of the hut symbolize and how were they arranged?

The ceiling in the hut was made of planks (that is, from boards hewn from logs). The upper boundary of the hut was the ceiling. The boards were supported by “Matitsa” - a particularly thick beam, which was cut into the upper crown when the frame was erected. The matitsa ran across the entire hut, fastening and holding the walls, ceiling and base of the roof. For a house, the mother was the same as the root for a tree, and the mother for a person: the beginning, support, foundation. Various objects were hung from the motherboard. A hook was nailed here for hanging the ochep with a cradle (a flexible pole, even with a slight push, such a cradle swayed). Only that house was considered full-fledged, where the fireplace creaks under the ceiling, where the children, growing up, nurse the younger ones. Ideas about the father's house, happiness, and good luck were associated with the mother. It is no coincidence that when setting off on the road, it was necessary to hold on to the mat. The ceilings on the motherboard were always laid parallel to the floorboards. Floor is the boundary separating people from “non-humans”: brownies and others. The floor in the house was laid from halves of logs (hence the word “floorboards”), and it rested on thick beams cut into the lower crowns of the log house. The floorboards themselves were associated with the idea of the path The bed (and in the summer they often slept right on the floor) was supposed to be laid across the floorboards, otherwise the person would leave the house. And during matchmaking, the matchmakers tried to sit so that they could look along the floorboards, then they would conspire and take the bride away from the house.