Sholom Aleichem is a Jewish address exchanged between ordinary people when they meet. “Peace be with you” is what it means. This fictitious name was chosen for himself by a young author who wrote about ordinary people in their native language - Yiddish. Here is Sholom Aleichem, a writer. The photo shows a man with kind, insightful eyes and humor, which he transferred to the pages of his stories, novels and novels.

Childhood

Sholom Nokhumovich Rabinovich was born in 1859 into a poor family in Pereyaslavl in Little Russia. Then the family moved to the town of Voronkovo, also in Ukraine. The teenager's childhood was poisoned by her stepmother from the age of 13. In the cold winter, he often sat outside near the house, where he was not allowed. Now, if a cart or a cab had arrived, then the boy could have led them into an inhospitable house, where there were several closets with beds for guests. Then he himself could warm up. But in winter there are rich guests who do not stay at the visiting house of Nokhum Rabinovich. They prefer the hotel of Naum Yasnogradsky. Freezing Sholom dreams of finding a treasure that is buried somewhere in Voronkovo, and now, after the family went bankrupt, they live again in Pereyaslavl. So Sholom lived in a large, bankrupt family, where there were brothers, sisters, and stepmother’s children. Jews had great respect for learning; they always had a reverent attitude toward books. Therefore, everyone, even the poorest boys, went to school (for girls this was considered optional). The first “work” he wrote was a list of his stepmother’s curses, which he arranged in alphabetical order. It is at home that Sholom Aleichem looks at the changing guests. His biography is replenished by meeting many people who will later turn to the pages of his books. After school, the young man graduated from college and dreamed of continuing his studies in Zhitomir at the institute and becoming a teacher.

Wandering

But young Sholom Aleichem must earn his living. He wanders around small places, working as a tutor. No one stands on ceremony with him. He is often offered the floor instead of a bed, and his hunger annoys his hosts, who glare as food disappears from the table. At night it even happens to cradle small children. Finally, Sholom was lucky. At the age of 17, he ended up in a very rich house, where he teaches a fourteen-year-old girl. Everything is fine. But, as has been described more than once in literature, the teacher and student begin to experience tender feelings for each other. This is noticed by the father, who is a good judge of people. This will be Sholom Aleichem. The photo shows a kind but impractical man.

The girl's father immediately realized that young man no entrepreneurial streak. This guy won't suit you as a son-in-law. This glorious dreamer will not even make a good assistant in business. Therefore, the whole family leaves secretly at night. Waking up in the morning, Sholom Aleichem, whose biography suddenly takes a terrible turn, discovers that he is completely alone in the house. The payment is left in a visible place for him, and that’s it. It is unknown where to look for your love.

Marriage

Sholom wandered around Little Russia for many years until he persuaded his beloved to run away from home. They got married against her parents' wishes. And two years later the father-in-law died, and in 1885 a huge fortune fell on the young family. An inexperienced player on the Kyiv and Odessa stock exchanges quickly lost his entire inheritance in five years. He is not a businessman - a simple-minded Sholom Aleichem. His biography, as his father-in-law had foreseen, would take a different path.

Becoming a writer

In 1888, Sholom Aleichem began to engage in publishing with the remainder of his funds. Collections of the “Jewish People's Library” appear in print. He looked for Jewish talents throughout vast Russia and found them in shops, shoemakers, and funeral parlors. He paid very high fees and financially supported elderly writers. He began writing and publishing himself. His novels “Stempenyu” and “Iosele the Nightingale” are published. And in 1894 he began a new novel, the main one in his life, “Tevye the Milkman.” This is how Sholom Aleichem, a Jewish writer, is gradually born.

Jewish pogroms

In 1903-1905, the writer's family lived poorly on literary fees in Kyiv. It is big, there are six children in it. And now in the south and southwest of the country there is a terrible wave of Jewish pogroms. People are tortured before they die.

Innocent people are beaten with stones, shovels, axes, women and girls are raped. Jewish houses and shops are destroyed, property is destroyed, synagogues are destroyed, holy books. But the police are silent, as if nothing is happening, and if they react, it is very sluggish. At this time, the writer was actively writing pamphlets, feuilletons and stories dedicated to these nightmares (“Gold”, “Shmulik”, “Joseph”). Because of these horrors, the writer’s family leaves first for Switzerland and then for the USA. This is how Sholom Aleichem becomes a wanderer. The biography turns new pages.

Overseas

The first time in the “land of freedom” goes well. He is advertised by both the Jewish press and American publications, comparing him to Mark Twain. But this quickly stops. Less than a year has passed since the publication of his new book “Motl Boy” is suspended, and the writer and his family are forced to return to Russia.

At home

There is no money in the family, and the writer travels around the country with readings of his books. In 1908 he fell ill with tuberculosis. He has been engaged in literary activity for 25 years, he is loved and appreciated, and publishers make money from his works.

The family is poor. And now Jews all over the country are raising money to buy the rights to publish his books. This was successful, and they were handed over to the author. A sick writer goes to Germany for treatment. Finds him there World War. He and his family are deported to Russia. But due to hostilities, it is impossible to return to it.

America again

Here he will spend two years before his death, dreaming of returning to his native land and being buried next to his father in Kyiv. His grandchildren are already growing up. Bel Kaufman, who wrote Up the Down Staircase, is his own granddaughter and has many fond memories of her grandfather.

In 1916, Sholem Aleichem died in America, far from his homeland. The biography, briefly outlined, has come to an end. It must be said that he will be buried in front of a huge crowd of people in a cemetery in New York. And his books live on and are read with no less interest than at the time they were written.

As in any other language, in Hebrew you can greet each other with the most different ways. And just like most other languages, greetings in Hebrew go back a very long time. They reflect the history of cultural contacts of the people, their psychological type and characteristics of thinking.

Speaking about Jewish greetings, we must not forget about borrowings (direct or indirect) from “Jewish languages of the Diaspora,” for example, Yiddish.

Features of secular and religious speech etiquette

Modern Hebrew is the language of everyday communication in Israel, and it reflects the peculiarities of today's life in the country. Therefore, we can say that there are two linguistic structures in Israel. One of them is more consistent with the secular population of Israel, and the second with the traditional, religious population.

Hebrew greetings illustrate this division. Of course, one cannot say that these “sets do not intersect at all.” However, secular and religious types of speech etiquette differ from each other.

Some expressions characteristic of the speech of religious people are included in secular speech etiquette. Sometimes they are used deliberately to give the statement an ironic tone with a “taste” of the archaic - “antique.” As if, for example, in Russian speech, you turned to a friend: “Be healthy, boyar!” or greeted their guests: “Welcome, dear guests!” at a friendly party.

The difference between greetings in Russian and Hebrew

In Russian, when meeting, people usually wish them health by saying “Hello!” (that is, literally: “Be healthy!” But hearing a wish for health in Hebrew - לבריות le-vriYut — your Israeli interlocutor will most likely say in surprise: “I didn’t sneeze” or “I guess we didn’t raise our glasses.” Wishing health as a greeting is not customary in Hebrew.

Expression

תהיה בריאquiet bars, which can be translated as “Hello!”, will be, rather, an informal form of farewell - “Be healthy!” (as in Russian).

Common greetings in Hebrew

The basic Jewish greeting is שלום shalom ( literally , "world"). People used this word to greet each other back in Biblical times. Interestingly, in Jewish tradition it also sometimes replaces the name of God. Meaning of the word shalom in the language it is much broader than just “the absence of war”, and in the greeting it is not just a wish for “peaceful skies above your head”.

Word שלום shalom- cognate with adjective שלם SHALEM- “whole, filled.” Greetings " shalom“means, therefore, not only a wish for peace, but also for inner integrity and harmony with oneself.

“Shalom” can be said both when meeting and when parting.

Expressions שלום לך Shalom LechA(with or without addressing a person by name) (“peace be upon you”) and לום אליכם shalom aleikhem(MM) (“peace be upon you”) refer to a higher style. It is customary to answer the latter ואליכם שלום ve-aleikhem shalom. This is a literal translation (tracing) from Arabic Hello. This answer also suggests high style, and in some cases, a certain amount of irony. You can answer more simply, without a conjunction ve,אליכם שלום AleikhEm shalom.

In a conversation with a religious person in response to a greeting שלום can often be heard שלום וברכה shalom at vrakha- “peace and blessings.” Or he may continue your greeting שלום shalom in words - וברכה u-vrahA. This is also acceptable in small talk, although too elegant.

In the mornings in Israel, people exchange greetings טוב בוקר boker tov! ("Good morning!"). Sometimes in response to this you can hear: בוקר אור boker or ("bright morning") or בוקר מצויין boxer metsuYan. ("great morning"). But they rarely say that.

As for the Russian expression “Good day!”, then when translated literally into Hebrew - יום טוב yom tov, it will turn out more like congratulations on the holiday (although more often in this case a different expression is used). The interlocutor may be surprised.

Instead they say צהוריים טובים TzohorAim ToVim(literally, “Good afternoon!”). But when we say goodbye, it’s quite possible to say יום טוב לך yom tov lecha. Here – precisely in the meaning of “Have a nice day!”

Expressions ערב טוב Erev tov“good evening” and לילה טוב Layla tov“Good night” in Hebrew is no different in usage from Russian. It is perhaps worth paying attention to the fact that the word “night” in Hebrew is male, therefore the adjective טוב “good, kind” will also be masculine.

Greetings from other languages

In addition to greetings that have Hebrew roots, greetings from other languages can often be heard in Israel.

At the beginning of a new era spoken language The language of ancient Judea was not Hebrew, but Aramaic. Nowadays it is perceived as high style, the language of the Talmud, and is sometimes used to give words a touch of irony.

In modern colloquial Hebrew the expression צפרא טבא numeral tab- “good morning” in Aramaic. Sometimes it can be heard in response to the usual טוב בוקר boker tov.

In this case, your interlocutor will turn out to be either a religious person of advanced age, or someone who wants to demonstrate his education and give the morning greeting a touch of light irony.

You can, for example, compare this with the situation when, in response to a neutral “Good morning!” you will hear “Greetings!”

Young Israelis often use English word"Hai!" Perhaps it caught on because it sounds similar to the Hebrew word for “life” (remember the popular toast לחיים le-chaim- "for a life").

In colloquial Hebrew you can also find greetings from Arabic: ahalan or, less commonly, marhaba(the second is more often pronounced with a joking tone).

Greetings and wishes on Shabbat and holidays

In most languages, greetings depend on the time of day, and in Jewish culture, also on the days of the week.

On Shabbat and holidays, special greetings are used in Hebrew.

On Friday evening and Saturday it is customary to greet each other with the words שבת שלום Shabbat Shalom. Saturday evening, after מו צאי שבת MotzaHey Shabbat(“the outcome of the Sabbath”) you can often hear the wish שבוע טוב ShavUa tov (“good week”). This applies to both religious and secular circles

Among older people or repatriates, instead of Shabbat shalom, you can hear greetings in Yiddish: gut Shabes(“good Saturday”), and at the end of Saturday - and gute wow(“good week”)

Just as in the case of Aramaic, the use of Yiddish in Israel in greetings has an informal, slightly humorous connotation.

Before the beginning of a new month (according to the Jewish calendar) and on its first day, the greeting is חודש טוב Khodesh tov - “Good month.”

"Holiday" in Hebrew is called חג hag, מועד mOed or טוב יום yom tov. However, to greet a holiday, only one of these words is most often used - חג שמח hag samEah! – « Happy holiday! In Jewish New Year people wish each other “Have a good year!” – שנה טובה SHANA TOVA! The word shana ("year") in Hebrew female, accordingly, the adjective - tovA will also be feminine.

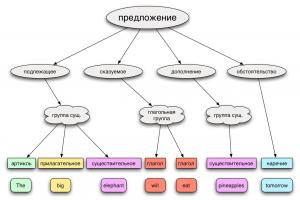

Greetings in the form of questions

Greeting each other, wishing good morning or evenings, people often ask, “How are you?” or “How are you?”

In Hebrew the expressions מה שלומך? ma shlomkha?(M) ( mA shlomEh? (F)) are similar to the Russian “How are you?” By the way, they are written the same way, and you can read them correctly only based on the context.

Literally, these phrases would mean something like: “How is your world doing?” We can say that each person has his own world, his own inner “shalom”. Naturally, in ordinary speech this expression is not taken literally, but serves as a neutral greeting formula.

In rare cases, you may be addressed in the third person: שלומו של כבודו? מה Ma shlomO shel kvodO?(or - ma shlom kvodO?) - “How are you doing, dear one?” This will mean either irony or high style and emphasized respect (as in Polish language address "pan")

In addition, such a refined address can be used in youth speech and slang as a reference to comedic dialogues from the “cult” Israeli film “ Hagiga ba-snooker" - "Billiards party."

One of the most common and style-neutral greetings in Hebrew is נשמה? מה ma nishma? (literally, “What do you hear?”).

The expressions מה קורה are used in a similar sense. Ma kore? – (literally, “What’s going on?”) and מה העניינים ma HainyangIm? ("How are you?"). Both of them are used in informal settings, in colloquial speech, in a friendly conversation.

Even more simply, in the “that’s what they say on the street” style, it sounds אתך מה ma itkhA? (M) or (ma itAkh? (F) (literally, “What’s wrong with you?”). However, unlike Russian, this jargon does not correspond to the question: “What’s wrong with you?”, but simply means : “How are you?” However, in a certain situation it can actually be asked if the state of the interlocutor causes concern.

It is customary to answer all these polite questions in a secular environment בסדר הכל תודה TodA, Akol be-sEder or simply בסדר be-seder(literally, “thank you, everything is fine.” In religious circles, the generally accepted answer is השם ברוך barUh ours(“Glory be to God,” literally, “Blessed be the Lord”). This expression is often used in everyday communication of secular people, without giving the speech any special connotation.

Greeting the New Arrivals

Greetings can also include addressing “new arrivals.”

When people come or arrive somewhere, they are addressed with the words “Welcome!” In Russian, this phrase is usually used in formal speech.

Hebrew expressions הבא ברוך barUh habA(M), ברוכה הבאה bruhA habaA(F) or ברוכים הבאים BruhIm habaIm(MM and LJ) (literally, “blessed is the one who has arrived (the ones who arrived)”) are found in ordinary colloquial speech. This is how you can greet your guests, for example.

In general, in Hebrew, as in any other language, greetings are closely related to cultural and religious traditions. The differences in their use depend on general style communication situations, as well as the level of education and age of the speakers.

SHALOM ALEYCHEM ( שָׁלוֹם עֲלֵיכֶם , Sholem Aleichem, Sholem Aleichem; pseudonym, real name Shalom (Sholem) Rabinovich; 1859, Pereyaslavl, Poltava province, now Pereyaslav-Khmelnitsky, Kyiv region, – 1916, New York), Jewish writer. One of the classics (along with Mendele Mokher Sfarim and I. L. Perets) of Yiddish literature. He wrote in Yiddish, as well as Hebrew and Russian.

Born into a family that observed Jewish traditions, but was not alien to ideas X askals. Father Shalom Aleichem a, Menachem-Nokhum Rabinovich, was a wealthy man, but later he went bankrupt; his mother worked in a shop. Shalom Aleichem spent his childhood in the town of Voronkovo (Voronka) in the Poltava province (Voronkovo became the prototype of Kasrilovka-Mazepovka in the writer’s stories). Then, impoverished, the family returned to Pereyaslavl. Shalom Aleichem received a thorough Jewish education, studying the Bible and Talmud at cheder and at home, under the supervision of his father, until he was almost 15 years old. In 1873–76 studied at the Russian gymnasium in Pereyaslavl, after graduating from which he became a private teacher of the Russian language. At the same time, he wrote his first story in Russian, “The Jewish Robinson Crusoe.”

In 1877–79 was a home teacher in the family of a wealthy tenant Loev in the town of Sofievka, Kyiv province. Having fallen in love with his young student, Olga Loeva, Shalom Aleichem wooed her, but was refused and, leaving Loeva’s house, returned to Pereyaslavl. In 1881–83 was a state rabbi in the city of Lubny, where he became involved in social activities, trying to renew the life of the local Jewish community. At the same time, he published articles in the Hebrew magazine “ X Ha-Tzfira" and the newspaper " X a-Melitz." He also wrote in Russian, sent stories to various periodicals, but received refusals. Only in 1884 was the story “The Dreamers” published in the “Jewish Review” (St. Petersburg).

In May 1883, Shalom Aleichem married Olga Loeva, left his position as a government rabbi and moved to Bila Tserkva near Kyiv. For some time he worked as an employee for the sugar factory I. Brodsky (see Brodsky, family). In 1885, after the death of his father-in-law, Shalom Aleichem became the heir to a large fortune, started commercial affairs in Kiev, played on the stock exchange, but unsuccessfully, which soon led him to bankruptcy, but provided invaluable material for many stories, in particular for the cycle “ Menachem Mendel" (see below). Shalom Aleichem lived in Kyiv until 1890, after which, hiding from creditors, he traveled, visited Odessa, Chernivtsi, and went abroad to Paris and Vienna. In 1893 he returned to Kyiv after his mother-in-law collected the remains of her late husband’s fortune and helped repay his debts.

In 1888–90 acted as the publisher of the almanac-yearbook “Di Yiddishe Folks Libraries” (see below). In 1892, having settled in Odessa, he tried to continue his publishing activities, publishing the magazine “Kol Mevasser”, a supplement to the “Di Yiddish Folks Library”. In 1893, Shalom Aleichem returned to Kyiv and again took up stock exchange activities.

In 1900, he took part in performances at evenings in Kyiv, Berdichev and Bila Tserkva together with M. Varshavsky, who in 1901 Shalom Aleichem helped to publish a collection of poems and songs (with his preface).

Shalom Aleichem’s favorite form of communication with readers was the evenings at which he spoke reading stories; during 1905 he performed in Vilna, Kovno, Riga, Lodz, Libau and many other cities. A significant event of this year was the acquaintance with I. D. Berkovich, future son-in-law and translator of almost all of Shalom Aleichem’s works into Hebrew.

The turbulent revolutionary events in Russia and especially the pogrom in Kyiv in October 1905 forced Shalom Aleichem and his family to leave. In 1905–1907 he lived in Lvov, visited Geneva, London, visited many cities in Galicia and Romania, and at the end of October 1906 he arrived in New York, where he was warmly received by the Jewish community. He performed at the Grand Theater in front of the famous Jewish troupe of J. Adler, and in the summer of 1907 he moved to Switzerland. In New York, Shalom Aleichem managed to publish the first chapters of the story “The Boy Motl”, and in May 1908 he went on a tour reading his stories in Poland and Russia. During his performances, Shalom Aleichem fell ill with pulmonary tuberculosis and was confined to bed for several months. At the insistence of doctors, he went to a resort in Italy. In connection with the 25th anniversary of Shalom Aleichem’s creative activity, which was solemnly celebrated in October 1908, an anniversary committee was created in Warsaw, which bought all rights to publish Shalom Aleichem’s works from the publishers and handed them over to the writer. In the same year, a multi-volume collection of the works of Shalom Aleichem, the so-called “Yubileum-oysgabe” (“Anniversary Edition”, vol. 1–14, 1908–14), began to be published in Warsaw, which included almost all of the writer’s works published before the First World War . In 1909, the publishing house Contemporary issues"(St. Petersburg) released a collection of works by Shalom Aleichem in Russian, which was warmly received by the public. Financial difficulties, however, haunted Shalom Aleichem until the end of his life.

From 1908 to 1914, Shalom Aleichem was treated at resorts in Italy, Switzerland, Austria and Germany, but did not interrupt his creative activity, following socio-political and literary events. However, at the beginning of 1913, the disease worsened again. The First World War found Shalom Aleichem in Germany. As a Russian citizen, he was interned in neutral Denmark, from where he moved to New York in December 1914.

In 1915–16 continued public speaking, including to earn money. He visited Cleveland, Detroit, Cincinnati, Toronto and Montreal. The last performance took place in Philadelphia in March 1916. For treatment, the writer often went to a sanatorium in the town of Lakewood (near New York). In May 1916, Shalom Aleichem died. Several hundred thousand people came to the writer's funeral (Jewish businesses in New York were closed that day).

In the early 1880s, after much thought, Shalom Aleichem came to the decision to write in Yiddish. In 1883, in A. Tsederbaum’s weekly “Yudishes Folksblat” (St. Petersburg), Shalom Aleichem published works in Yiddish - the story “Zvei Steiner” (“Two Stones”) and the story “Di Vybores” (“Elections”), first signed with a pseudonym Shalom Aleichem (“Peace be with you” - roughly equivalent to the Russian “Hello!”). The weekly published most of his works of this period: the humorous story “An iberschreibung zwishn zwei alte haveyrim” (“Correspondence of two old friends”, 1884), the novel “Natasha” (in later editions “Taibele”, 1885), “Kontor-geshichte "("Office History", 1885), "Di Veltraise" (" Trip around the world", 1886) and others.

In the 1880s. Shalom Aleichem developed as a writer. He tried himself in poetry, wrote several poems in Russian (clearly imitating N.A. Nekrasov), including “The Jew’s Daughter”, “Jewish Tricksters”, “Sleep, Alyosha” and others. He published newspaper sketches: “Pictures of Berdichevskaya Street”, “Pictures of Zhytomyr Street”, “Letters Intercepted at the Post Office”, “From the Road” and others, in which the denunciation of the morals of the Jewish quarters was accompanied by a sad lyrical intonation.

Story " X eher un Niedereker" ("Higher and Inferior") deals with the social stratification of society, and the author sympathizes with the poor, following the tradition of Mendele Moher Sfarim. Shalom Aleichem brought a reconciling note of humor to the feuilleton genre and a light of hope to the realistic narrative, a confidential tone to the conversation with the reader. Shalom Aleichem used a variety of artistic techniques in a realistic story (for example, writing, caricature, Gogol's hyperbolization of the situation, expressive characterization and many others).

In the second half of the 1880s. Shalom Aleichem began a fight against pulp literature, of which the novelist Shomer was a vivid embodiment for him. In his pamphlet “The Trial of Shomer” (1888), Shalom Aleichem denounced the epigonic lightweight plots and far-fetched collisions of pulp novels. In the article “The Theme of Poverty in Jewish Literature,” he contrasted them with the works of Mendele Moher Sfarim, I. Linetsky and M. Spector; he later published a series of essays entitled Yiddishe Shreibers (Jewish Writers), in which he advocated the vernacular nature of literature capable of defending the humane ideals of the Enlightenment.

In 1887, Shalom Aleichem published a story for children, “Dos Meserl” (“The Knife”), in the newspaper Judishes Folksblat, which was warmly received by Jewish criticism of all directions. In 1888, Shalom Aleichem's father died, to whose memory he dedicated the book of stories “A bintle blumen, oder Poetry on gramen” (“Bouquet of Flowers, or Poems in Prose”).

An important stage in the creative biography of Shalom Aleichem was the publication in 1888–90. almanac-yearbook “Di Yiddishe Folksbibliotek”, in which he collected the best writing forces of that time (Mendele Moher Sfarim, I. L. Perets, I. Linetsky, A. Gottlober, J. Dinezon and others). Shalom Aleichem published in this almanac his novels “Stempenyu” (1888) and “Yosele the Nightingale” (1889), which describe tragic fates talented people-nuggets. A continuation of the satirical line of early stories and feuilletons was the novel “Sender Blank un zain gezindl” (“Sender Blank and his family”, 1888).

The collections of “Di Yiddish folk libraries” caused controversy in the Hebrew and Russian-Jewish press about the role of the Yiddish language and literature in the life of Jews. The almanac strengthened the position of the Yiddish language and literature in it. However, financial collapse did not allow Shalom Aleichem to continue publishing.

In the next publication that Shalom Aleichem undertook, the magazine “Kol Mevasser” (see above), he was the only author. The publication did not last long, but Shalom Aleichem managed to publish in it a number of literary critical articles and the first cycle of stories “London” from the satirical novel he conceived in the letters “Menachem-Mendl” (the novel is constructed in the form of correspondence between an unlucky stockbroker and his wife Sheine-Sheindl). For the first time in Jewish literature the image of the so-called Luftmench (“man of the air” appeared); This is a small-town Jew who tirelessly tries to get rich and invariably slides to the social bottom. This novel, which Shalom Aleichem wrote throughout his life, brought him worldwide fame.

In 1891–92 Shalom Aleichem also collaborated in the Russian-language “Odessa List” and in the Hebrew press. Together with I. Ravnitsky he published in the newspaper “ X a-Melits” critical articles-feuilletons in the section “Kvurat Sofrim” (“Burial Ground of Writers”, under the joint pseudonym “Eldad u-Meydad”).

Satirical comedy about stock speculators “Yakne” X oz, oder Der gräuser bersen-spiel" ("Yakne X Oz, or the Great Exchange Game", 1894; staged on stage under the title “Oyswurf /“The Monster”/ or “Shmuel Pasternak”) was a huge success with the public. Published as a separate book, it was confiscated by the censor. In the same year, the writer in the almanac “Der X oizfreund" (Warsaw, vol. 4) published the beginning of one of his most significant works, "Tevye der Milhiker" ("Tevye the Milkman"): Tevye's letter to the narrator and his first monologue, "Happiness has arrived." A charming, simple village worker, standing firmly on the ground, he was, as it were, the antipode of Menachem Mendel, the lightweight “man of air.” Shalom Aleichem continued to work on the novel Menachem Mendel. Already in the next, fifth volume of “Der X oizfrend" (1896) Shalom Aleichem published the second chapter of the series, thematically related to his own stock exchange game ("Paper"). Two images in the work of Shalom Aleichem - comically touching and lyrically epic - developed in parallel.

At the same time, Shalom Aleichem continued to publish satirical feuilletons in the American press in Yiddish: in the newspapers Di Toib (Pittsburgh) and Philadelfer Stotzeitung. Since the 1890s Shalom Aleichem became interested in Palestinophilism, and then in Zionism, which was reflected in the writing of a number of propaganda brochures: “Oif Yishuv Eretz Yisroel” (“On the Settlement of Eretz Israel”, Kiev, 1890), “Oif vos badarfn idn a land?” (“Why do the Jews need a country?”, Warsaw, 1898), “Doctor Theodor Herzl” (Odessa, 1904), “Tsu unzere schwester in Zion” (“To our sisters in Zion”, Warsaw, 1917). Shalom Aleichem's controversial (sympathetic, but also skeptical) attitude towards Zionism is expressed in the unfinished novel “Mashiehs Tsaytn” (“Times of the Messiah”). The story “Don Quixote from Mazepovka” was published in Hebrew in I. Linetsky’s magazine “Pardes”, in “Voskhod” in Russian - a series of fairy tales “Ghetto Tales” (1898), and in “Voskhod Books” - the stories “Pinta- robber" and "His Excellency's Caftan" (both 1899).

The beginning of the publication of the Krakow weekly Der Yud (1899–1902) served as a creative stimulus for Shalom Aleichem. In the first issues of Der Yud, Shalom Aleichem published two new monologues from Tevye the Milkman: “The Chimera” and “The Children of Today” and the third series of letters from Menachem-Mendl entitled “Millions.” He is also published in the weekly newspapers “Di Yiddishe Volkszeitung” and “Froenvelt” (1902–1903) and the daily newspaper “Der Freund” (since 1903). At the turn of the century, the following stories were also published: “Der Zeiger” (“The Hours”), “Purim”, “Hanukkah-gelt” (“Hanukkah Money”) and others, in which mature mastery was already felt. At the same time, Shalom Aleichem published the first stories from the series “Gantz Berdichev” (“All Berdichev”; later called “Naye Kasrilevke” / “New Kasrilovka”) and the cycle “Di kleine menchelekh mit di kleine X asheiges" (in Russian translation: "In small world little people"). In the Warsaw publishing house "Bildung" Shalom Aleichem published the story "Dos farkischefter schneiderl" ("The Enchanted Tailor", 1901), permeated with folklore, humor and elements of mysticism. Later, it was included in one cycle with the stories “Finf un zibtsik toiznt” (“Seventy-five thousand”, 1902), “A vigrishner ticket” (“Winning ticket”, 1909) and others dedicated to the life of the town.

Since the early 1900s. Shalom Aleichem was engaged exclusively in literature, and his writing skills grew noticeably. Published in 1902 in Der Yud, the stories (including in the form of monologues) “Ven ikh bin Rothschild” (“If I were a Rothschild”), “Oifn fiddle” (“On the violin”), “Dreyfus in Kasrilevke” ( “Dreyfus in Kasrilovka”), “Der Deitsch” (“The German”) and many others are examples of that special humor, “laughter through tears”, which became known in world literature as “the humor of Shalom Aleichem” and was most fully manifested in the story “Motl Pacey dem haznes” (in Russian translation “Boy Motl”, 1907). After the Kishinev pogrom (see Kishinev) in 1903, Shalom Aleichem became the compiler of the collection “ X ilf" ("Help"), which the Warsaw publishing house "Tushia" published to help victims of the pogrom, and entered into correspondence with L. Tolstoy, A. Chekhov, V. Korolenko, M. Gorky, inviting them to take part in the collection. Soon, the Tushiya publishing house published the first collected works of Shalom Aleichem in four volumes, Ale verk fun Sholem Aleichem (Warsaw, 1903). Another Warsaw publishing house, Bicher Far Ale, published a two-volume book, Derzeilungen un monologn (Stories and Monologues, 1905). In 1909, Shalom Aleichem published the story “Kaver oats” (“Graves of the Ancestors”) from the series “Railway Stories” in the newspaper “Di naye welt” (Warsaw).

One of the main works of Shalom Aleichem was the novel “Di blondzhde stern” (“Wandering Stars”), on which Shalom Aleichem worked in 1909–10. The first part of the novel “The Actors” first appeared in the newspaper “Di Naye Welt” in 1909–10, the second part “The Drifters” was published in the newspaper “Der Moment” (1910–11). The novel became, as it were, the completion of Shalom Aleichem’s trilogy about the plight of Jewish talents (see above “Yosele the Nightingale” and “Stempenya”). “Wandering Stars” is Shalom Aleichem’s highest achievement in the genre of the novel, which was not hindered by some sentimentality of the plot. The novel went through a huge number of editions in Yiddish, English, Russian and many other languages of the world. Numerous dramatizations of the novel have entered the repertoire of Jewish theater troupes in America and Europe. In the 1920s I. Babel wrote a script for a silent film based on the novel (published as a separate book: “Wandering Stars. Film Script.” M., 1926). In 1992, the film “Wandering Stars” (directed by V. Shidlovsky) was released in Russia.

A kind of literary commentary on the trial of M. Beilis was published in the newspaper “ X aint" novel by Shalom Aleichem "Der blutiker shpas" ("The Bloody Joke", Lodz, 1912; in the stage version "Shwer zu zayn aid" / "It's hard to be a Jew" /), which caused conflicting responses in the press of that time, but later highly appreciated by critics, in particular, by S. Niger. The plot is based on a hoax: two student friends, a Jew and a Christian, exchanged passports as a joke; As a result, a Christian with a Jewish passport becomes a victim of a blood libel and undergoes painful trials. Shalom Aleichem hoped to publish the novel in Russian translation, but due to censorship obstacles during his lifetime this did not materialize. The novel appeared in Russian only in 1928 (translation by D. Glickman; republished in 1991 in the almanac “Year after Year” - an appendix to the “Soviet Gameland” with an afterword by H. Bader (1920–2003); in Israel - a separate book translated by Gita and Miriam Bachrach, T.-A., 1990).

The American stage in the work of Shalom Aleichem was, despite his fatal illness, extremely eventful. In 1915–16 Shalom Aleichem worked intensively on the autobiographical novel “Funem Yarid” (“From the Fair”), in which he gave an epic description of his father’s house, courtyard, his childhood, and adolescence. According to the plan, the novel was supposed to consist of ten parts. The first two parts of the novel were published as a separate book in New York in 1916. The third part began to be published in February 1916 by the newspaper Var X ait" (N.-Y.), but it remained unfinished. Shalom Aleichem considered this novel to be his spiritual testament: “I put into it the most valuable thing I have - my heart. Read this book from time to time. Perhaps she... will teach us how to love our people and appreciate the treasures of their spirit.”

During the same period, Shalom Aleichem published the second part of his already famous story “The Boy Motl” - “In America”. It was also published in 1916 in the newspaper Var X ait.” Shalom Aleichem, through the mouth of the orphan Motla, the son of Pacey the Cantor, talks about the life of Jewish emigrants in America. Sometimes ironically, sometimes humorously, Shalom Aleichem depicts the life and morals of the former Kasrilov residents who found refuge in the “blessed” America, which the author, with all his skepticism, evaluates positively, contrasts it with Russia, shaken by pogroms, the destruction of towns and a disastrous war. Anti-war motives were reflected in the cycle of stories by Shalom Aleichem “Maises mit toyznt un ein nakht” (“Tales of the Thousand and One Nights”, 1914).

At the beginning of 1915, Shalom Aleichem was hired as a contract employee new newspaper Der Tog, where he posted his correspondence twice a week. Chapters of the novel “From the Fair” were also published here. In this newspaper, Shalom Aleichem began publishing the novel “Der Mistake” (“The Mistake”), but did not complete the publication due to a breakdown in relations with the newspaper. At the same time, the comedy “Der Groiser Gevins” (“Big Win”) was written; in some stage versions it was called “Zwei X undert toyznt” - “200 thousand”), first published in the magazine “Zukunft” (N.Y., 1916). The play is based on the plot of sudden enrichment and the associated changes in human character and way of life. The play entered the repertoire of many theater groups and became one of the highest achievements of the Moscow GOSET (Sh. Mikhoels in the role of Shimele Soroker).

The significance of Shalom Aleichem's work for Jewish literature is enormous. More than the work of any other Jewish writer, the works of Shalom Aleichem express the desire and ability of the Jewish people to be reborn. Shalom Aleichem was able to show Jewish life as a “Jewish comedy”, and not as the tragedy of dispersion, which most of his predecessors and contemporaries wrote about. At the same time, the works of Shalom Aleichem contain a pronounced tragic element, but it arises against the background not of hopelessness, but of the breadth of opportunities that life provides. The reader comes to the conclusion that destructive forces will give way to creation.

After the death of Shalom Aleichem in the American Jewish press (the newspaper “Var” X ait", "Zukunft") were published in 1916–18. individual works from his creative heritage. In the newspaper "Tog" in 1923–24. materials “From the Archives of Sholem Aleichem” were published (including 166 letters from the writer). In 1918, the collection “Tsum gedank fun Sholem Aleichem” (“In Memory of Shalom Aleichem”; edited by S. Niger and I. Tsinberg with the assistance of the I. L. Peretz Foundation) was published in Petrograd, which collected memories of the writer and his letters. The publication in 1926 in New York of the book “Dos Sholem Aleichem Bukh” (“The Book of Shalom Aleichem”; edited and with comments by I. D. Berkovich; 2nd edition 1958, with the assistance of the Yiddisher Kultur-Farband) marked the beginning of the scientific studying the life and work of Shalom Aleichem. In 1917–25 In New York, 28 volumes of the most complete edition of the works of Shalom Aleichem “Ale Verk” were published.

In Soviet Russia, the work of Shalom Aleichem was initially perceived as a legacy of Jewish “bourgeois culture”, which did not fit into the framework of proletarian revolutionary culture, but by the mid-1930s, with the appeal of the Soviet ideological leadership to the “national idea”, the bans were lifted, and the name Shalom Aleichem is recognized as the property of “Jewish folk literature.” Shalom Aleichem was recognized as a classic; hundreds of articles and reviews were written about his work. The works of Shalom Aleichem were studied by critics M. Wiener, A. Gurshtein, I. Dobrushin, I. Drucker, X. Remenik and others. A monograph by E. Spivak “Sholem Aleichems shprakh un style” (“Language and Style of Shalom Aleichem”, Kyiv, 1940) and a collective collection “Sholem Aleichem. Zamlung fun kritishe artiklen un material" - "Shalom Aleichem. Collection of critical articles and materials" (Kyiv, 1940). The 80th anniversary of the birth of Shalom Aleichem was celebrated at the state level. In 1948, the scientific publication of Shalom Aleichem’s works “Ale Verk” began (M., publishing house “Der Emes”), only three volumes were published, the publication ceased due to the general defeat of Jewish culture in 1948–52. (See Jews in the Soviet Union 1945–53). For the 100th anniversary of the birth of Shalom Aleichem, a collection of works in six volumes was published in Russian (M., publishing house " Fiction", 1959–61, with a foreword by R. Rubina). A decade later, a new, expanded six-volume edition was launched there (M., 1971–74). In 1994, a facsimile collection of the works of Shalom Aleichem in 4 volumes in Yiddish was published in Riga (Vaidelote publishing house with a foreword by A. Gurshtein and illustrations by the artist G. Inger /1910-95/).

Research work on cataloging and collecting articles and books by Shalom Aleichem in various languages, as well as letters and manuscripts of the writer, is carried out by the Beth Shalom Aleichem museum in Tel Aviv, founded in 1964 on the initiative of I. D. Berkovich (officially opened since 1967). It has a publishing department, which over 30 years has published 17 books dedicated to the life and work of Shalom Aleichem, in particular, the collection of Shalom Aleichem “Oif vos badarfn idn a land?” (“Why do the Jews need a country?”, T.-A., 1978), which included his appeals and “Zionist stories,” including the forgotten story “Di Ershte Yiddishe Republik” (“The First Jewish Republic”), as well as the book “Briv fun Sholem Aleichem” (“Letters of Shalom Aleichem”, T.-A., 1995, editor A. Lis), which published 713 letters of Shalom Aleichem for the period from 1879 to 1916; many saw the light for the first time. Beth Shalom Aleichem also conducts cultural and educational events dedicated to Jewish culture and literature in Yiddish.

The works of Shalom Aleichem have been translated into dozens of languages around the world. He, along with M. Twain, A.P. Chekhov and B. Shaw, is recognized by UNESCO as one of the greatest humorous writers in world literature. Monographs have been written about Shalom Aleichem - in Yiddish: D. Lobkovsky “Sholem Aleichem un zaine X eldn" ("Shalom Aleichem and His Heroes", T.-A., 1959), collective "Sholem Aleichem's Bukh" ("The Book of Shalom Aleichem", edited by I. D. Berkovich, N.-Y., 1967; Soviet monographs - see above), in Hebrew: A. Beilin (Merhavia, 1945, 2nd edition 1959), G. Kresel (T.-A., 1959), Sh. Niger (T.-A., 1960 ), M. Play (N.-Y., 1965), D. B. Malkina " X a-universali be-Shalom Aleichem” (“Universal in the works of Shalom Aleichem”, T.-A., 1970), D. Miron (T.-A., 1970; 2nd edition 1976), I. Sha- Lavan (T.-A., 1975), M. Zhitnitsky (T.-A., 1977), H. Shmeruk (T.-A., 1980).

The Shalom Aleichem Memorial House-Museum also exists in Ukraine, in the writer’s homeland in the city of Pereyaslav-Khmelnitsky. In 1997, a monument to Shalom Aleichem was erected in Kyiv.

Brother of Shalom Aleichem, Wolf (Vevik) Rabinovich(1864–1939), a glove maker by profession, author of a book of memoirs about Shalom Aleichem “Mein Bruder Sholem Aleichem” (“My brother Shalom Aleichem”, Kiev, 1939; partially published in Russian in the collection “Sholom Aleichem - Writer and Man” , M., 1984, in full in the “Collection of articles on Jewish history and literature”, Rehovot, 1994; books 3 and 4, translation by Sh. Zhidovetsky).

Granddaughter of Shalom Aleichem, Bel Kaufman(1912, Odessa, – 2014, New York), American writer. She came to the USA with her parents in 1924. Author of stories about New York children and the work of teachers. Her novel “Up the Staircase Leading Down” (N.Y., 1966; Russian translation in the journal “Foreign Literature”, M., 1967, No. 6) was published in the 1970s. popular in the USSR. She also wrote the novel “Love and So On” (N.Y., 1981). Author of memoirs about Shalom Aleichem: “Papa Sholom Aleichem” (published in Russian in the collection “Sholom Aleichem - Writer and Man”, M., 1984). Every year, on the anniversary of the death of Shalom Aleichema, she gathered fans of the writer’s work in her home, in the synagogue or in the IVO building and organized public readings of his stories. She gave lectures on the work of Shalom Aleichem.

SHALOM ALEYCHEM ( שָׁלוֹם עֲלֵיכֶם , Sholem Aleichem, Sholem Aleichem; pseudonym, real name Shalom (Sholem) Rabinovich; 1859, Pereyaslavl, Poltava province, now Pereyaslav-Khmelnitsky, Kyiv region, – 1916, New York), Jewish writer. One of the classics (along with Mendele Mokher Sfarim and I. L. Perets) of Yiddish literature. He wrote in Yiddish, as well as Hebrew and Russian.

Born into a family that observed Jewish traditions, but was not alien to ideas X askals. Shalom Aleichem's father, Menachem-Nochum Rabinovich, was a wealthy man, but later went bankrupt; his mother traded in a shop. Shalom Aleichem spent his childhood in the town of Voronkovo (Voronka) in the Poltava province (Voronkovo became the prototype of Kasrilovka-Mazepovka in the writer’s stories). Then, impoverished, the family returned to Pereyaslavl. Shalom Aleichem received a thorough Jewish education, studying the Bible and Talmud at cheder and at home, under the supervision of his father, until he was almost 15 years old. In 1873–76 studied at the Russian gymnasium in Pereyaslavl, after graduating from which he became a private teacher of the Russian language. At the same time, he wrote his first story in Russian, “The Jewish Robinson Crusoe.”

In 1877–79 was a home teacher in the family of a wealthy tenant Loev in the town of Sofievka, Kyiv province. Having fallen in love with his young student, Olga Loeva, Shalom Aleichem wooed her, but was refused and, leaving Loeva’s house, returned to Pereyaslavl. In 1881–83 was a state rabbi in the city of Lubny, where he became involved in social activities, trying to renew the life of the local Jewish community. At the same time, he published articles in the Hebrew magazine “ X Ha-Tzfira" and the newspaper " X a-Melitz." He also wrote in Russian, sent stories to various periodicals, but received refusals. Only in 1884 was the story “The Dreamers” published in the “Jewish Review” (St. Petersburg).

In May 1883, Shalom Aleichem married Olga Loeva, left his position as a government rabbi and moved to Bila Tserkva near Kyiv. For some time he worked as an employee for the sugar factory I. Brodsky (see Brodsky, family). In 1885, after the death of his father-in-law, Shalom Aleichem became the heir to a large fortune, started commercial affairs in Kiev, played on the stock exchange, but unsuccessfully, which soon led him to bankruptcy, but provided invaluable material for many stories, in particular for the cycle “ Menachem Mendel" (see below). Shalom Aleichem lived in Kyiv until 1890, after which, hiding from creditors, he traveled, visited Odessa, Chernivtsi, and went abroad to Paris and Vienna. In 1893 he returned to Kyiv after his mother-in-law collected the remains of her late husband’s fortune and helped repay his debts.

In 1888–90 acted as the publisher of the almanac-yearbook “Di Yiddishe Folks Libraries” (see below). In 1892, having settled in Odessa, he tried to continue his publishing activities, publishing the magazine “Kol Mevasser”, a supplement to the “Di Yiddish Folks Library”. In 1893, Shalom Aleichem returned to Kyiv and again took up stock exchange activities.

In 1900, he took part in performances at evenings in Kyiv, Berdichev and Bila Tserkva together with M. Varshavsky, who in 1901 Shalom Aleichem helped to publish a collection of poems and songs (with his preface).

Shalom Aleichem’s favorite form of communication with readers was the evenings at which he spoke reading stories; during 1905 he performed in Vilna, Kovno, Riga, Lodz, Libau and many other cities. A significant event of this year was the acquaintance with I. D. Berkovich, future son-in-law and translator of almost all of Shalom Aleichem’s works into Hebrew.

The turbulent revolutionary events in Russia and especially the pogrom in Kyiv in October 1905 forced Shalom Aleichem and his family to leave. In 1905–1907 he lived in Lvov, visited Geneva, London, visited many cities in Galicia and Romania, and at the end of October 1906 he arrived in New York, where he was warmly received by the Jewish community. He performed at the Grand Theater in front of the famous Jewish troupe of J. Adler, and in the summer of 1907 he moved to Switzerland. In New York, Shalom Aleichem managed to publish the first chapters of the story “The Boy Motl”, and in May 1908 he went on a tour reading his stories in Poland and Russia. During his performances, Shalom Aleichem fell ill with pulmonary tuberculosis and was confined to bed for several months. At the insistence of doctors, he went to a resort in Italy. In connection with the 25th anniversary of Shalom Aleichem’s creative activity, which was solemnly celebrated in October 1908, an anniversary committee was created in Warsaw, which bought all rights to publish Shalom Aleichem’s works from the publishers and handed them over to the writer. In the same year, a multi-volume collection of the works of Shalom Aleichem, the so-called “Yubileum-oysgabe” (“Anniversary Edition”, vol. 1–14, 1908–14), began to be published in Warsaw, which included almost all of the writer’s works published before the First World War . In 1909, the publishing house “Modern Problems” (St. Petersburg) published a collection of works by Shalom Aleichem in Russian, which was warmly received by the public. Financial difficulties, however, haunted Shalom Aleichem until the end of his life.

From 1908 to 1914, Shalom Aleichem was treated at resorts in Italy, Switzerland, Austria and Germany, but did not interrupt his creative activity, following socio-political and literary events. However, at the beginning of 1913, the disease worsened again. The First World War found Shalom Aleichem in Germany. As a Russian citizen, he was interned in neutral Denmark, from where he moved to New York in December 1914.

In 1915–16 continued public speaking, including to earn money. He visited Cleveland, Detroit, Cincinnati, Toronto and Montreal. The last performance took place in Philadelphia in March 1916. For treatment, the writer often went to a sanatorium in the town of Lakewood (near New York). In May 1916, Shalom Aleichem died. Several hundred thousand people came to the writer's funeral (Jewish businesses in New York were closed that day).

In the early 1880s, after much thought, Shalom Aleichem came to the decision to write in Yiddish. In 1883, in A. Tsederbaum’s weekly “Yudishes Folksblat” (St. Petersburg), Shalom Aleichem published works in Yiddish - the story “Zvei Steiner” (“Two Stones”) and the story “Di Vybores” (“Elections”), first signed with a pseudonym Shalom Aleichem (“Peace be with you” - roughly equivalent to the Russian “Hello!”). The weekly published most of his works of this period: the humorous story “An iberschreibung zwishn zwei alte haveyrim” (“Correspondence of two old friends”, 1884), the novel “Natasha” (in later editions “Taibele”, 1885), “Kontor-geshichte "("Office History", 1885), "Di Veltraise" ("Trip Around the World", 1886) and others.

In the 1880s. Shalom Aleichem developed as a writer. He tried himself in poetry, wrote several poems in Russian (clearly imitating N.A. Nekrasov), including “The Jew’s Daughter”, “Jewish Tricksters”, “Sleep, Alyosha” and others. He published newspaper sketches: “Pictures of Berdichevskaya Street”, “Pictures of Zhytomyr Street”, “Letters Intercepted at the Post Office”, “From the Road” and others, in which the denunciation of the morals of the Jewish quarters was accompanied by a sad lyrical intonation.

Story " X eher un Niedereker" ("Higher and Inferior") deals with the social stratification of society, and the author sympathizes with the poor, following the tradition of Mendele Moher Sfarim. Shalom Aleichem brought a reconciling note of humor to the feuilleton genre and a light of hope to the realistic narrative, a confidential tone to the conversation with the reader. Shalom Aleichem used a variety of artistic techniques in a realistic story (for example, writing, caricature, Gogol's hyperbolization of the situation, expressive characterization and many others).

In the second half of the 1880s. Shalom Aleichem began a fight against pulp literature, of which the novelist Shomer was a vivid embodiment for him. In his pamphlet “The Trial of Shomer” (1888), Shalom Aleichem denounced the epigonic lightweight plots and far-fetched collisions of pulp novels. In the article “The Theme of Poverty in Jewish Literature,” he contrasted them with the works of Mendele Moher Sfarim, I. Linetsky and M. Spector; he later published a series of essays entitled Yiddishe Shreibers (Jewish Writers), in which he advocated the vernacular nature of literature capable of defending the humane ideals of the Enlightenment.

In 1887, Shalom Aleichem published a story for children, “Dos Meserl” (“The Knife”), in the newspaper Judishes Folksblat, which was warmly received by Jewish criticism of all directions. In 1888, Shalom Aleichem's father died, to whose memory he dedicated the book of stories “A bintle blumen, oder Poetry on gramen” (“Bouquet of Flowers, or Poems in Prose”).

An important stage in the creative biography of Shalom Aleichem was the publication in 1888–90. almanac-yearbook “Di Yiddishe Folksbibliotek”, in which he collected the best writing forces of that time (Mendele Moher Sfarim, I. L. Perets, I. Linetsky, A. Gottlober, J. Dinezon and others). Shalom Aleichem published in this almanac his novels “Stempenyu” (1888) and “Yosele the Nightingale” (1889), which describe the tragic fates of talented people-nuggets. A continuation of the satirical line of early stories and feuilletons was the novel “Sender Blank un zain gezindl” (“Sender Blank and his family”, 1888).

The collections of “Di Yiddish folk libraries” caused controversy in the Hebrew and Russian-Jewish press about the role of the Yiddish language and literature in the life of Jews. The almanac strengthened the position of the Yiddish language and literature in it. However, financial collapse did not allow Shalom Aleichem to continue publishing.

In the next publication that Shalom Aleichem undertook, the magazine “Kol Mevasser” (see above), he was the only author. The publication did not last long, but Shalom Aleichem managed to publish in it a number of literary critical articles and the first cycle of stories “London” from the satirical novel he conceived in the letters “Menachem-Mendl” (the novel is constructed in the form of correspondence between an unlucky stockbroker and his wife Sheine-Sheindl). For the first time in Jewish literature the image of the so-called Luftmench (“man of the air” appeared); This is a small-town Jew who tirelessly tries to get rich and invariably slides to the social bottom. This novel, which Shalom Aleichem wrote throughout his life, brought him worldwide fame.

In 1891–92 Shalom Aleichem also collaborated in the Russian-language “Odessa List” and in the Hebrew press. Together with I. Ravnitsky he published in the newspaper “ X a-Melits” critical articles-feuilletons in the section “Kvurat Sofrim” (“Burial Ground of Writers”, under the joint pseudonym “Eldad u-Meydad”).

Satirical comedy about stock speculators “Yakne” X oz, oder Der gräuser bersen-spiel" ("Yakne X Oz, or the Great Exchange Game", 1894; staged on stage under the title “Oyswurf /“The Monster”/ or “Shmuel Pasternak”) was a huge success with the public. Published as a separate book, it was confiscated by the censor. In the same year, the writer in the almanac “Der X oizfreund" (Warsaw, vol. 4) published the beginning of one of his most significant works, "Tevye der Milhiker" ("Tevye the Milkman"): Tevye's letter to the narrator and his first monologue, "Happiness has arrived." A charming, simple village worker, standing firmly on the ground, he was, as it were, the antipode of Menachem Mendel, the lightweight “man of air.” Shalom Aleichem continued to work on the novel Menachem Mendel. Already in the next, fifth volume of “Der X oizfrend" (1896) Shalom Aleichem published the second chapter of the series, thematically related to his own stock exchange game ("Paper"). Two images in the work of Shalom Aleichem - comically touching and lyrically epic - developed in parallel.

At the same time, Shalom Aleichem continued to publish satirical feuilletons in the American press in Yiddish: in the newspapers Di Toib (Pittsburgh) and Philadelfer Stotzeitung. Since the 1890s Shalom Aleichem became interested in Palestinophilism, and then in Zionism, which was reflected in the writing of a number of propaganda brochures: “Oif Yishuv Eretz Yisroel” (“On the Settlement of Eretz Israel”, Kiev, 1890), “Oif vos badarfn idn a land?” (“Why do the Jews need a country?”, Warsaw, 1898), “Doctor Theodor Herzl” (Odessa, 1904), “Tsu unzere schwester in Zion” (“To our sisters in Zion”, Warsaw, 1917). Shalom Aleichem's controversial (sympathetic, but also skeptical) attitude towards Zionism is expressed in the unfinished novel “Mashiehs Tsaytn” (“Times of the Messiah”). The story “Don Quixote from Mazepovka” was published in Hebrew in I. Linetsky’s magazine “Pardes”, in “Voskhod” in Russian - a series of fairy tales “Ghetto Tales” (1898), and in “Voskhod Books” - the stories “Pinta- robber" and "His Excellency's Caftan" (both 1899).

The beginning of the publication of the Krakow weekly Der Yud (1899–1902) served as a creative stimulus for Shalom Aleichem. In the first issues of Der Yud, Shalom Aleichem published two new monologues from Tevye the Milkman: “The Chimera” and “The Children of Today” and the third series of letters from Menachem-Mendl entitled “Millions.” He is also published in the weekly newspapers “Di Yiddishe Volkszeitung” and “Froenvelt” (1902–1903) and the daily newspaper “Der Freund” (since 1903). At the turn of the century, the following stories were also published: “Der Zeiger” (“The Hours”), “Purim”, “Hanukkah-gelt” (“Hanukkah Money”) and others, in which mature mastery was already felt. At the same time, Shalom Aleichem published the first stories from the series “Gantz Berdichev” (“All Berdichev”; later called “Naye Kasrilevke” / “New Kasrilovka”) and the cycle “Di kleine menchelekh mit di kleine X asheiges" (in Russian translation: "In the small world of small people"). In the Warsaw publishing house "Bildung" Shalom Aleichem published the story "Dos farkischefter schneiderl" ("The Enchanted Tailor", 1901), permeated with folklore, humor and elements of mysticism. Later, it was included in one cycle with the stories “Finf un zibtsik toiznt” (“Seventy-five thousand”, 1902), “A vigrishner ticket” (“Winning ticket”, 1909) and others dedicated to the life of the town.

Since the early 1900s. Shalom Aleichem was engaged exclusively in literature, and his writing skills grew noticeably. Published in 1902 in Der Yud, the stories (including in the form of monologues) “Ven ikh bin Rothschild” (“If I were a Rothschild”), “Oifn fiddle” (“On the violin”), “Dreyfus in Kasrilevke” ( “Dreyfus in Kasrilovka”), “Der Deitsch” (“The German”) and many others are examples of that special humor, “laughter through tears”, which became known in world literature as “the humor of Shalom Aleichem” and was most fully manifested in the story “Motl Pacey dem haznes” (in Russian translation “Boy Motl”, 1907). After the Kishinev pogrom (see Kishinev) in 1903, Shalom Aleichem became the compiler of the collection “ X ilf" ("Help"), which the Warsaw publishing house "Tushia" published to help victims of the pogrom, and entered into correspondence with L. Tolstoy, A. Chekhov, V. Korolenko, M. Gorky, inviting them to take part in the collection. Soon, the Tushiya publishing house published the first collected works of Shalom Aleichem in four volumes, Ale verk fun Sholem Aleichem (Warsaw, 1903). Another Warsaw publishing house, Bicher Far Ale, published a two-volume book, Derzeilungen un monologn (Stories and Monologues, 1905). In 1909, Shalom Aleichem published the story “Kaver oats” (“Graves of the Ancestors”) from the series “Railway Stories” in the newspaper “Di naye welt” (Warsaw).

One of the main works of Shalom Aleichem was the novel “Di blondzhde stern” (“Wandering Stars”), on which Shalom Aleichem worked in 1909–10. The first part of the novel “The Actors” first appeared in the newspaper “Di Naye Welt” in 1909–10, the second part “The Drifters” was published in the newspaper “Der Moment” (1910–11). The novel became, as it were, the completion of Shalom Aleichem’s trilogy about the plight of Jewish talents (see above “Yosele the Nightingale” and “Stempenya”). “Wandering Stars” is Shalom Aleichem’s highest achievement in the genre of the novel, which was not hindered by some sentimentality of the plot. The novel went through a huge number of editions in Yiddish, English, Russian and many other languages of the world. Numerous dramatizations of the novel have entered the repertoire of Jewish theater troupes in America and Europe. In the 1920s I. Babel wrote a script for a silent film based on the novel (published as a separate book: “Wandering Stars. Film Script.” M., 1926). In 1992, the film “Wandering Stars” (directed by V. Shidlovsky) was released in Russia.

A kind of literary commentary on the trial of M. Beilis was published in the newspaper “ X aint" novel by Shalom Aleichem "Der blutiker shpas" ("The Bloody Joke", Lodz, 1912; in the stage version "Shwer zu zayn aid" / "It's hard to be a Jew" /), which caused conflicting responses in the press of that time, but later highly appreciated by critics, in particular, by S. Niger. The plot is based on a hoax: two student friends, a Jew and a Christian, exchanged passports as a joke; As a result, a Christian with a Jewish passport becomes a victim of a blood libel and undergoes painful trials. Shalom Aleichem hoped to publish the novel in Russian translation, but due to censorship obstacles during his lifetime this did not materialize. The novel appeared in Russian only in 1928 (translation by D. Glickman; republished in 1991 in the almanac “Year after Year” - an appendix to the “Soviet Gameland” with an afterword by H. Bader (1920–2003); in Israel - a separate book translated by Gita and Miriam Bachrach, T.-A., 1990).

The American stage in the work of Shalom Aleichem was, despite his fatal illness, extremely eventful. In 1915–16 Shalom Aleichem worked intensively on the autobiographical novel “Funem Yarid” (“From the Fair”), in which he gave an epic description of his father’s house, courtyard, his childhood, and adolescence. According to the plan, the novel was supposed to consist of ten parts. The first two parts of the novel were published as a separate book in New York in 1916. The third part began to be published in February 1916 by the newspaper Var X ait" (N.-Y.), but it remained unfinished. Shalom Aleichem considered this novel to be his spiritual testament: “I put into it the most valuable thing I have - my heart. Read this book from time to time. Perhaps she... will teach us how to love our people and appreciate the treasures of their spirit.”

During the same period, Shalom Aleichem published the second part of his already famous story “The Boy Motl” - “In America”. It was also published in 1916 in the newspaper Var X ait.” Shalom Aleichem, through the mouth of the orphan Motla, the son of Pacey the Cantor, talks about the life of Jewish emigrants in America. Sometimes ironically, sometimes humorously, Shalom Aleichem depicts the life and morals of the former Kasrilov residents who found refuge in the “blessed” America, which the author, with all his skepticism, evaluates positively, contrasts it with Russia, shaken by pogroms, the destruction of towns and a disastrous war. Anti-war motives were reflected in the cycle of stories by Shalom Aleichem “Maises mit toyznt un ein nakht” (“Tales of the Thousand and One Nights”, 1914).

At the beginning of 1915, Shalom Aleichem was hired as a contract employee of the new newspaper Der Tog, where he published his correspondence twice a week. Chapters of the novel “From the Fair” were also published here. In this newspaper, Shalom Aleichem began publishing the novel “Der Mistake” (“The Mistake”), but did not complete the publication due to a breakdown in relations with the newspaper. At the same time, the comedy “Der Groiser Gevins” (“Big Win”) was written; in some stage versions it was called “Zwei X undert toyznt” - “200 thousand”), first published in the magazine “Zukunft” (N.Y., 1916). The play is based on the plot of sudden enrichment and the associated changes in human character and way of life. The play entered the repertoire of many theater groups and became one of the highest achievements of the Moscow GOSET (Sh. Mikhoels in the role of Shimele Soroker).

The significance of Shalom Aleichem's work for Jewish literature is enormous. More than the work of any other Jewish writer, the works of Shalom Aleichem express the desire and ability of the Jewish people to be reborn. Shalom Aleichem was able to show Jewish life as a “Jewish comedy”, and not as the tragedy of dispersion, which most of his predecessors and contemporaries wrote about. At the same time, the works of Shalom Aleichem contain a pronounced tragic element, but it arises against the background not of hopelessness, but of the breadth of opportunities that life provides. The reader comes to the conclusion that destructive forces will give way to creation.

After the death of Shalom Aleichem in the American Jewish press (the newspaper “Var” X ait", "Zukunft") were published in 1916–18. individual works from his creative heritage. In the newspaper "Tog" in 1923–24. materials “From the Archives of Sholem Aleichem” were published (including 166 letters from the writer). In 1918, the collection “Tsum gedank fun Sholem Aleichem” (“In Memory of Shalom Aleichem”; edited by S. Niger and I. Tsinberg with the assistance of the I. L. Peretz Foundation) was published in Petrograd, which collected memories of the writer and his letters. The publication in 1926 in New York of the book “Dos Sholem Aleichem Bukh” (“The Book of Shalom Aleichem”; edited and with comments by I. D. Berkovich; 2nd edition 1958, with the assistance of the Yiddisher Kultur-Farband) marked the beginning of the scientific studying the life and work of Shalom Aleichem. In 1917–25 In New York, 28 volumes of the most complete edition of the works of Shalom Aleichem “Ale Verk” were published.

In Soviet Russia, the work of Shalom Aleichem was initially perceived as a legacy of Jewish “bourgeois culture”, which did not fit into the framework of proletarian revolutionary culture, but by the mid-1930s, with the appeal of the Soviet ideological leadership to the “national idea”, the bans were lifted, and the name Shalom Aleichem is recognized as the property of “Jewish folk literature.” Shalom Aleichem was recognized as a classic; hundreds of articles and reviews were written about his work. The works of Shalom Aleichem were studied by critics M. Wiener, A. Gurshtein, I. Dobrushin, I. Drucker, X. Remenik and others. A monograph by E. Spivak “Sholem Aleichems shprakh un style” (“Language and Style of Shalom Aleichem”, Kyiv, 1940) and a collective collection “Sholem Aleichem. Zamlung fun kritishe artiklen un material" - "Shalom Aleichem. Collection of critical articles and materials" (Kyiv, 1940). The 80th anniversary of the birth of Shalom Aleichem was celebrated at the state level. In 1948, the scientific publication of Shalom Aleichem’s works “Ale Verk” began (M., publishing house “Der Emes”), only three volumes were published, the publication ceased due to the general defeat of Jewish culture in 1948–52. (See Jews in the Soviet Union 1945–53). For the 100th anniversary of the birth of Shalom Aleichem, a collection of works in six volumes was published in Russian (M., Khudozhestvennaya Literatura Publishing House, 1959–61, with a foreword by R. Rubina). A decade later, a new, expanded six-volume edition was launched there (M., 1971–74). In 1994, a facsimile collection of the works of Shalom Aleichem in 4 volumes in Yiddish was published in Riga (Vaidelote publishing house with a foreword by A. Gurshtein and illustrations by the artist G. Inger /1910-95/).

Research work on cataloging and collecting articles and books by Shalom Aleichem in various languages, as well as letters and manuscripts of the writer, is carried out by the Beth Shalom Aleichem museum in Tel Aviv, founded in 1964 on the initiative of I. D. Berkovich (officially opened since 1967). It has a publishing department, which over 30 years has published 17 books dedicated to the life and work of Shalom Aleichem, in particular, the collection of Shalom Aleichem “Oif vos badarfn idn a land?” (“Why do the Jews need a country?”, T.-A., 1978), which included his appeals and “Zionist stories,” including the forgotten story “Di Ershte Yiddishe Republik” (“The First Jewish Republic”), as well as the book “Briv fun Sholem Aleichem” (“Letters of Shalom Aleichem”, T.-A., 1995, editor A. Lis), which published 713 letters of Shalom Aleichem for the period from 1879 to 1916; many saw the light for the first time. Beth Shalom Aleichem also conducts cultural and educational events dedicated to Jewish culture and literature in Yiddish.

The works of Shalom Aleichem have been translated into dozens of languages around the world. He, along with M. Twain, A.P. Chekhov and B. Shaw, is recognized by UNESCO as one of the greatest humorous writers in world literature. Monographs have been written about Shalom Aleichem - in Yiddish: D. Lobkovsky “Sholem Aleichem un zaine X eldn" ("Shalom Aleichem and His Heroes", T.-A., 1959), collective "Sholem Aleichem's Bukh" ("The Book of Shalom Aleichem", edited by I. D. Berkovich, N.-Y., 1967; Soviet monographs - see above), in Hebrew: A. Beilin (Merhavia, 1945, 2nd edition 1959), G. Kresel (T.-A., 1959), Sh. Niger (T.-A., 1960 ), M. Play (N.-Y., 1965), D. B. Malkina " X a-universali be-Shalom Aleichem” (“Universal in the works of Shalom Aleichem”, T.-A., 1970), D. Miron (T.-A., 1970; 2nd edition 1976), I. Sha- Lavan (T.-A., 1975), M. Zhitnitsky (T.-A., 1977), H. Shmeruk (T.-A., 1980).

The Shalom Aleichem Memorial House-Museum also exists in Ukraine, in the writer’s homeland in the city of Pereyaslav-Khmelnitsky. In 1997, a monument to Shalom Aleichem was erected in Kyiv.

Brother of Shalom Aleichem, Wolf (Vevik) Rabinovich(1864–1939), a glove maker by profession, author of a book of memoirs about Shalom Aleichem “Mein Bruder Sholem Aleichem” (“My brother Shalom Aleichem”, Kiev, 1939; partially published in Russian in the collection “Sholom Aleichem - Writer and Man” , M., 1984, in full in the “Collection of articles on Jewish history and literature”, Rehovot, 1994; books 3 and 4, translation by Sh. Zhidovetsky).

Granddaughter of Shalom Aleichem, Bel Kaufman(1912, Odessa, – 2014, New York), American writer. She came to the USA with her parents in 1924. Author of stories about New York children and the work of teachers. Her novel “Up the Staircase Leading Down” (N.Y., 1966; Russian translation in the journal “Foreign Literature”, M., 1967, No. 6) was published in the 1970s. popular in the USSR. She also wrote the novel “Love and So On” (N.Y., 1981). Author of memoirs about Shalom Aleichem: “Papa Sholom Aleichem” (published in Russian in the collection “Sholom Aleichem - Writer and Man”, M., 1984). Every year, on the anniversary of the death of Shalom Aleichema, she gathered fans of the writer’s work in her home, in the synagogue or in the IVO building and organized public readings of his stories. She gave lectures on the work of Shalom Aleichem.

שלום־עליכם Sholem Aleichem or Shulem Aleichem) is a traditional Jewish greeting meaning peace to you. The answer to this greeting is vealeichem shalom (peace to you too). In modern Hebrew, only a short form of greeting is used - shalom.The greeting "sholom aleichem" is mentioned in the Jerusalem Talmud, and in the form singular- and in the Babylonian Talmud. The plural form began to be used in relation to one person under the influence of the Arabic language (cf. salaam alaikum).

This greeting (in Ashkenazi pronunciation) was used as his pseudonym by the classic of Jewish literature Solomon Naumovich Rabinovich.

Similar greetings in other languages

- Salam alaikum - traditional Arabic and Muslim greeting

- Pax vobiscum is a liturgical exclamation in Catholicism. Goes back to Jesus Christ's greeting of his disciples (Gospel of Luke 24:36, Gospel of John 20:19, 20:21, 20:26). Apparently Jesus used a non-preserving Semitic phrase similar to the Hebrew expression.

Links

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.

See what “Shalom Aleichem” is in other dictionaries:

- (Ashkenazi pronunciation Sholom Aleichem) (Hebrew שָׁלוֹם עֲלֵיכֶם shālôm ʻalêḵem; Yiddish שלום־עליכם sholem Aleichem or Shulem Aleichem) traditional Jewish greeting, meaning bringing peace to you. The answer to this greeting is Aleichem Shalom (and... ... Wikipedia

This term has other meanings, see Shalom (meanings). This article lacks links to sources of information. Information must be verifiable, otherwise it may be questioned and deleted. You can... Wikipedia

Yiddish שלום עליכם Birth name: Solomon (Shlomo) Naumovich (Nokhumovich) Rabinovich Date of birth: February 18 (March 2 ... Wikipedia

See Sholom Aleichem. (Heb. enc.) ... Large biographical encyclopedia

Rothschilds- (Rothschilds) The Rothschilds are the most famous dynasty of European bankers, financial tycoons and philanthropists. The Rothschild dynasty, representatives of the Rothschild dynasty, the history of the dynasty, Mayer Rothschild and his sons, the Rothschilds and conspiracy theories,... ... Investor Encyclopedia

This term has other meanings, see Bila Tserkva (meanings). City of Belaya Tserkov, Ukrainian. Bila Church Flag Coat of Arms ... Wikipedia

- (Hebrew שלם Shin Lamed Mem, Arabic. سلم Sin Lam Mim) a three-letter root of Semitic languages, found in many words, many of which are used as names. The independent meaning of the root is “whole”, “safe”, ... ... Wikipedia

Or, more correctly, jargon (Judendeutsch) is a peculiar dialect that served as the folk language of the Jews, both in Germany and in many other European states. At present, when Jews in Western Europe have switched to native languages, E.... ... encyclopedic Dictionary F. Brockhaus and I.A. Ephron